Apologies if this post is a little old now, but i found it fascinating and thought your ideas were really interesting and I think I can help out.

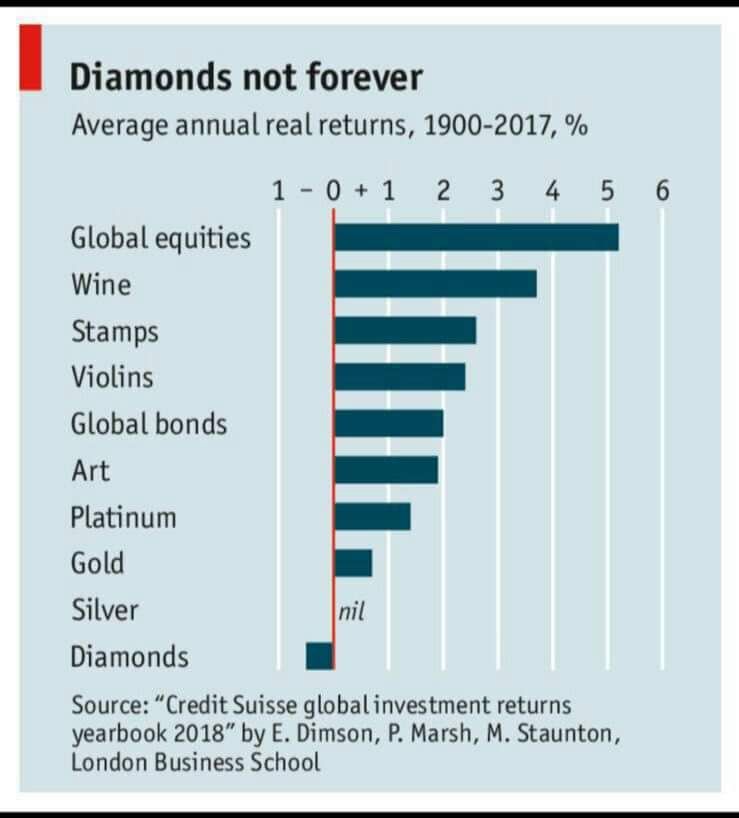

I first analyse the ‘store of value’ argument. If the assertion that is a token with no utility whatsoever should be able to maintain value indefinitely then I think this is provably false. The result is directly drawn from game theory and the nature of zero sum games. Classic economic theory tells us that all zero sum games are unstable (must end) because there is no Nash equilibrium strategy other than avoiding play. This is true despite the potential for new joiners and despite any external conditions (such as economic growth). In this case, ‘end’ can literally be taken to mean trading must stop. That is - there is one stable Nash equilibrium - a zero value for the ‘useless’ coin.

Back to the main question of this thread as I saw it. The question as it is originally asked is actually one around valuation. Asking “which coins are a store of value” is to me, very similar to asking, “which coins are valuable”.

We tend to think of the market as being separated into two types of transactors - one where the main purpose is speculative gains - one where the main purpose is to derive some utility through the holding of a token.

For me, there are several asset valuation models that are potentially applicable for a cryptocurrency such as bitcoin, Ethereum, or Nano. There applicability is actually dependent on whether we are analysing competitive or monopoly markets and I think there may be differences here between the examples listed. Let’s consider a few methods.

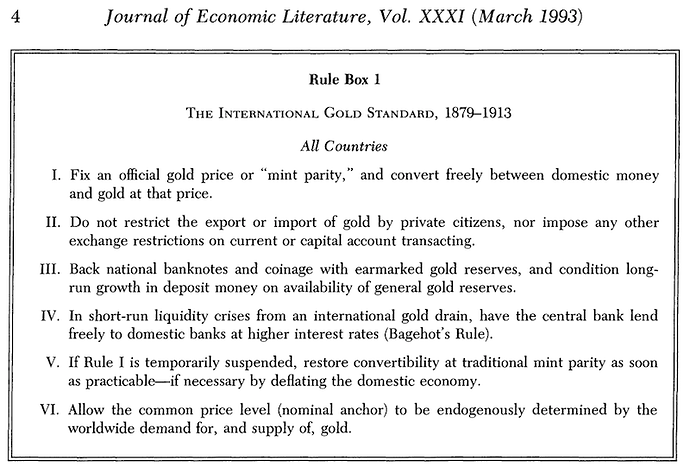

First, there is the valuation of standard (FIAT) currencies. I’m going to talk briefly about the concept of a carry trade - so skip this paragraph if you are familiar. Although it is thought that the vast majority of transactions in FIAT currency markets are speculative, this is generally considered to have a short term impact on the currency valuation itself. Normal FIAT currencies can be thought of as monopoly markets because they allow access to interest rates and because interest rates are set separately by different central banks. For example, a holder of YEN cannot simply earn a USD interest rates on their YEN. They must first convert their YEN into USD to earn the USD rate - and then back again. This process is fairly common and is referred to as a carry trade. It sets the long term direction of exchange rates.

My point in saying all this is not necessarily to explain the carry trade, which I am sure many of you are aware of, but rather to say that although the majority of trades are speculative, the actual long term value of the currencies actually tracks the carry trade fairly closely. That is to say - currency markets are not driven by speculators - but actually directly driven by those seeking to use the currency for what it is intended for. To see why this must be the case you need only consider the possible arbitrage opportunities by somebody who borrows YEN, paying YEN interest rates and then performs a carry trade on USD. If exchange rates did not move according to the carry trade it would be possible to make near risk free money like this, indefinitely.

Our analogy in the cryptocurrency space is this: the speculators cannot drive the value. In a way, this confirms our first result - a coin with no utility must have zero value in the end (speculation is not enough).

So now, a model for the valuation of a coin with utility - it is also based on economic theory, a Nash equilibrium. Since we are on ethresear.ch it seems only fitting to use Ethereum as our example. We should consider the scenario where a person buys Ethereum, (as the one, in effect, receiving a service) momentarily forgetting miners and other users.

Now, it could be that the person buying Ethereum is a speculator/‘hodl’ type transactor. However, we need to dismiss this notion, because, for reasons discussed it is not possible to identify the Nash equilibrium for such a transactor.

Therefore, we must consider a person or consortium purchasing Ethereum at time t. To make the argument easier, let’s also assume that they then sell the token at time t+1. We are left with the complication that holding the coin for one time period does not actually deliver a value directly. So what has the consortium gained? Well, they have won the right to hold the coin over that time period. It is the value of this right which determines the long run value of Ethereum.

It is, of course, possible to build our Nash Equilibrium based not only on direct financial gains from within the system but also from avoided costs outside the system.

I consider one of the most common use cases for the platform. Suppose that our consortium, who purchased Ethereum is actually running an ICO. In this case, the consortium includes all of the ICO participants. Strictly speaking they are separate entities all with distinct aims, but the example works better by consider them all as a single entity for a moment.

We need only to consider the cost of running the ICO outside of the Ethereum system versus within the system. When viewed as a single unit, the group purchase a lot of Ethereum, send it to another party, receiving a custom token in return. We assume for simplicity, that the party running the ICO then sell all of their Ethereum immediately (although this might not be the case).

It is easy to see that if you treat the entire group of transactors as a single unit, this is the same example as above. For the group, as a whole, the value in holding the token between t and t+1 is actually the same as the difference in cost between running an ICO inside and outside the system. Of course, it also depends on how many tokens are involved which scales this cost. Lets say that there are N Ethereum tokens involved and a total avoided cost of \pi N - that is - it is \pi N cheaper to run the ICO inside Ethereum than it is outside.

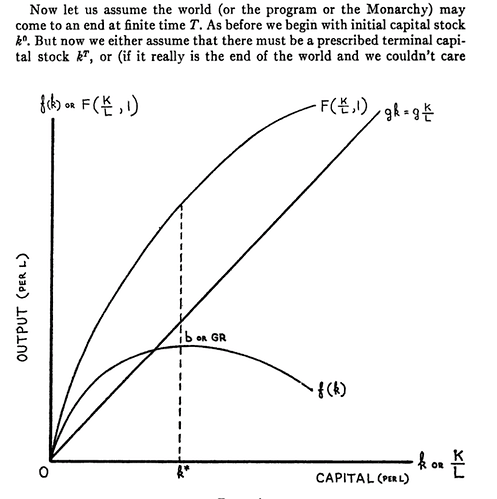

If we now call the per token avoided cost as \pi, it follows that a simple valuation for Ethereum emerges. The long term value of one Ethereum in USD should be the profit \pi divided by interest r for one USD.

Of course, there are many possible use cases. The formula only works for the best (most profitable) use case. This is because the largest values of \pi tends to set a value which, in effect, makes other use cases an unaffordable use of Ethereum.

Hope this was helpful and thanks all for reading.

(edit because piN wouldn’t show)