This post was co-authored by @samwilsn and @adietrichs, with significant input by @villanuevawill and the Quilt team.

Introduction

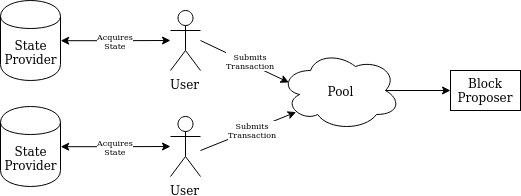

Ethereum 2.0’s statelessness means that transactions have to bring their own state. More precisely, for every transaction a block proposer (BP) wants to include into a block, they also have to include all state accessed by that transaction, as well as the corresponding witnesses. Neither the user creating the transaction nor the BP are assumed to hold state. Thus, a new kind of actor is required, whose role it is to hold and provide such state. This actor is commonly known as a state provider (SP).

Regardless of how BPs and SPs exchange state, it is likely going to be necessary for users to fetch state before creating a transaction. Examples include fetching contract bytecode to estimate gas cost or checking an account balance. This means SPs will expose a pull-like interface for users. An optional incentive layer could be added with payments for state via payment channels, although it seems feasible to start without such a system and rely on SPs altruistically providing state to users (as is currently the case in Ethereum 1.0).

Comparison Criteria

There are several different ways to integrate SPs into the overall system. In the following sections, we give an overview over several proposals. Besides a general description of each model, we compare the following properties:

State Access Restrictions

As transactions operate on the current state at the time of execution, their behaviour changes as the underlying state changes. In particular, for some transaction, the locations of state access might vary. This could either happen as a result of simple branching (e.g. if) or if the location is calculated at runtime. We refer to either case as a dynamic state access (DSA). In a stateless model, this complicates the transaction creation process. The problem is that it might not be possible to provide state for some of those transactions in advance (i.e. before the exact global state is known against which the tx will be executed). The models presented differ in the extent to which they support those transactions.

Under a model restricting dynamic state access, it seems very likely that Eth1 cannot become an Eth2 execution environment (EE) and will always require special treatment.

Incentives

The rewards for SPs are compared on:

- Who pays the reward, and how is it calculated?

- Are altruistic SPs viable initially, and if so, can incentives be added later?

Centralization Risks

Each model presents different levels of risk related to centralization:

- Who can censor transactions, and to what extent?

- How much state is a single SP expected to store? What hardware will be required?

- How much do BPs and SPs have to trust each other?

Timing Constraints

BPs have a fixed amount of time to propose a block. In this section, we will highlight operations in each model that might be constrained by this time limit.

Attributability of Missing State

In Eth1, miners can be certain that they will be paid as soon as the initial signature verification and balance and nonce checks for a given transaction are complete. In Eth2, this depends on whether missing state is an attributable fault. If it is, the BP can still be paid for a transaction failing due to missing state. Otherwise, transactions missing state will be non-includable, which BPs might only notice after running the full (potentially lengthy) transaction.

If BPs run transactions that fail due to missing state, and those transactions are non-includable (i.e. unable to pay fees), BPs are vulnerable to a nearly zero cost denial of service attack.

Models

| Model | State Access | Incentives | Centralization Risks | Timing Constraints |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct Push | Restricted | Altruism or Payment Channels | Well-known SP are preferred | None |

| Relayed Push | Unrestricted | Bundle Market or Exclusivity Period | Censorship potential | Update & transfer bundle within one slot |

| Pull | Unrestricted | Payment Channels | Well-known SP are preferred | Acquire bundle state within one slot |

Direct Push Model

A user acquires the necessary state directly from one or more SPs, then sends the transaction with that state attached to the network. Nodes maintain a pool of pending transactions, refreshing witnesses as blocks are produced. When creating a block, a BP chooses a subset of the pending transactions from the pool to include into the new block.

State Access Restrictions

The user creating a transaction is the only actor in the system providing state for that transaction. In general, there is no way to ensure that this state is sufficient for any state access occurring later on when the transaction is included into a block. Thus, under the Direct Push Model, only transactions where state access is predictable are possible. Besides transactions with purely static state access, contract creators could design their contracts to have predictable state access using annotations such as access lists, where the contract specifies all locations it can possibly access during execution. Together with ways to avoid dynamic state access patterns (see e.g. this related post by Vitalik in the Eth 1.x context), the resulting model might still offer sufficient functionality.

However, this would be a clear departure from the current Eth1 system, and would, in particular, make any plans to transition Eth1 into an Eth2 EE impossible.

Incentives

This model would just rely on the general SP network. As discussed above, it seems feasible to start without an incentive system.

Incentivization could be added via payment channels. Given that every user would have to have an open payment channel with one or several state providers, this option would be rather complex.

Centralization Risks

No individual SP can censor a transaction, since users are able to issue multiple queries to different SPs.

SPs can hold any subset of state, so the hardware requirements are minimal.

Monetary incentives would likely encourage some SP centralization, since users would need to trust SPs when purchasing state through a payment channel.

Timing Constraints

No timing constraints.

Attributability of Missing State

Missing state is attributable to the user. In most cases, a BP can include a transaction with insufficient state and have the user pay for it. The only exception is state missing for the initial signature verification or fee payment, in which case the transaction could not be included. Analogous to the Eth1 case, nodes in the network would be expected to drop such transactions from the transaction pool. Some restrictions would have to apply for maximum gas usage for these initial transaction parts.

Key Points

- Main Benefit: Simplicity. No further specialized SPs or incentive systems necessary. No particular timing constraints.

- Main Drawback: Only works with transactions that know in advance all state they could potentially access. This limits functionality of the overall system. While some mitigations seem possible, composability would remain severely limited. In particular, Eth1 could not become an Eth2 EE under this model.

Relayed Push Model

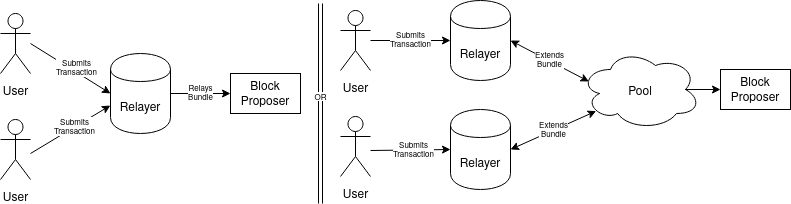

Users send transactions to one of several Relayers (specialized SPs). The relayer bundles the transactions, attaches state and relays the bundle to the network. Nodes maintain a pool of pending bundles. As blocks are produced, relayers relay updates to their bundles, while all nodes refresh the corresponding witnesses. When creating a block, a BP chooses one pending up-to-date bundle from the pool to include into the new block.

Alternatively, if a pool of bundles proves infeasible, the system could function without it. Relayers only advertise the existence of bundles. A BP then reaches out to a relayer directly to acquire the bundle and include it into a new block.

State Access Restrictions

No restrictions. Having relayers publish updates to their bundles every slot ensures that the state provided for these bundles is sufficient. Furthermore, any new block only includes one bundle, preventing interference between bundles.

Incentives

Incentivizing relayers is complicated because, once state and witnesses have been revealed, users and/or BPs have the opportunity to recreate the bundle without the payment to the relayer.

Two possible solutions:

- In the case without a pool, transaction bundles are not public. Relayers sell the bundles with state attached to BPs (for a price lower than the transaction fees), forming a bundle market. There are several risks to BPs: a transaction might have been previously included in another block, otherwise become invalid, or pay lower transaction fees than advertised.

- Alternatively—with or without a pool—transactions can include a payment to a specific relayer. The user promises an exclusivity period (i.e. a couple of slots), during which the user may not create any other transactions. The EE would have to provide a method to “slash” users signing two or more transactions with overlapping exclusivity periods. As users don’t have a stake locked up, it is unclear how to deal with slashings for users without a sufficient account balance.

Centralization Risks

Depending on how the relayer incentives are structured:

- Assuming merging bundles is complex (because of DSA), a bundle market leads to high centralization and allows a single relayer to censor transactions. Because of the risks to BPs outlined above, BPs will likely prefer to deal with well-known and trusted relayers. Individual users will not be able to offer bundles with high enough fees to compete with these well-known relayers.

- Using an exclusivity period and a bundle pool leads to a higher degree of decentralization, at the cost of user convenience and a more complex pool implementation. Any user could in theory retrieve a bundle from the pool, extend it with their transaction, and relay it with a higher fee payment.

Timing Constraints

To support arbitrary transactions, any bundle included into a block has to be up-to-date. Relayers have to download the previous block, create and send an update for their bundle, have that update reach the BP, and have the BP include the updated bundle into a new block, all within one slot’s time.

Attributability of Missing State

Missing state is attributable to the relayer. Relayers could be required (or could voluntarily choose) to send a “refund transaction” along with any relayed transaction. The refund transaction would be used to refund the BP if the original transaction were to fail due to missing state.

Key Points

- Main Benefit: No state access restrictions.

- Drawbacks:

- The version with a pool of transaction bundles might be infeasible do to the large size of bundles (as opposed to the Eth1 pool of individual transactions) and the strict timing constraints.

- Without a pool, bundles cannot be combined, resulting in only one relayer contributing to any given block. Relayers would be expected to centralize, which introduces censorship concerns.

- Even in the pool case, it is unclear whether the combining of bundles would work well enough to fully alleviate censorship concerns.

- Complex incentive system.

Pull Model

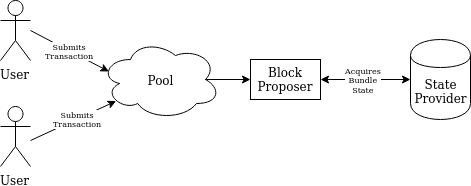

Users send transactions to the network, where nodes maintain a pool of pending transactions. Before creating a block, a BP chooses a subset of the pending transactions from the pool and sends them to a SP requesting the state for this transaction bundle. Having received that state, the BP can include the bundle into the new block.

In order for intermediary nodes and the BP to verify the validity of a transaction before the full state is attached by the SP, the user would have to attach enough state to the transaction to verify the signature and fee payment ability. This transaction part would therefore have to be standardized across EEs, with the simplest option being a verification function provided by all EEs.

Alternatively, a Value-Holding EE (VHEE) could be enshrined. Any transaction would use this VHEE for fee payments. Nodes in the network would understand the VHEE and could thus verify transaction validity.

In both cases, nodes in the network would be expected to update the witnesses for this attached state as new blocks arrive.

BPs have no way to predict the actual gas used by any bundle of combined transactions. In particular, any transaction in that bundle could invalidate all further transactions in the same bundle, for example by reducing the balances of their senders to 0. To mitigate that, BPs could “overbundle”, i.e. send more transactions to the SP than they expect to fit into a block. The SP would provide state for those transactions until the block limit is reached. In the VHEE case, transactions could additionally be required to include a list of VHEE addresses and the maximum amount they might reduce the balance of that address by. In this way, a BP could pick transactions in such a way as to prevent earlier transactions invalidating later ones.

State Access Restrictions

No restrictions for the main transaction. The BP only reaches out to the SP when creating the block, ensuring the state returned is up to date. Even more importantly, by bundling the transactions and requesting state for the whole bundle at once, state is attached in the exact context these transactions are then included into the block. This ensures that the provided state is always sufficient. It constitutes one of the key differences to the Direct Push Model, where state is attached before the transactions are bundled, resulting in the restrictions of that model.

As the user would have to include state for signature verification and fee payment, this transaction part would technically have the same restrictions outlined in the Direct Push Model. However, those limitations would be insignificant in practice. As signature verification and fee payment also have predictable state access under Eth1, compatibility between Eth1 and Eth2 would not be impaired. Moreover, in case of a VHEE, the VHEE would be designed in such a way as to ensure predictable state access, making further restrictions unnecessary.

Incentives

The BP pays the SP for the provided state, e.g. via a payment channel. Depending on the trust between the BP and the SP, this could be done on a (trust-minimized) per-transaction basis or a (more efficient) per-bundle basis.

Centralization Risks

SPs must hold the entire state, which will require a substantial amount of storage. SPs will also be expected to execute transaction bundles quickly, so computing power is also required.

BPs will likely prefer to acquire state from SPs they’ve built trust with, to reduce the risk of griefing, increasing centralization.

However, no individual SP can censor a transaction, since the BP creates and orders the transaction bundle. An SP may withhold state for an entire bundle, but doing so would risk their reputation and the BP could easily retry with another SP.

Timing Constraints

A BP would have to reach out to an SP to acquire updated state for the pending bundle within one slot’s time.

Attributability of Missing State

SPs are always responsible for providing the state requested. BPs only pay after verifying this state is sufficient and are not allowed to include transactions with insufficient state into a block.

Key Points

- Benefits:

- No relevant state access restrictions.

- Less problematic timing constraints.

- No significant centralization risks. While it can be expected that a small subset of SPs will specialize in providing state for BPs, no SP can significantly interfere with the overall process. The worst a SP can do is not provide state when asked to do so.

- Main Drawback: Some standardization around signature verification necessary, either via verification scripts or via an enshrined VHEE.

Further Discussion

Preemptive Witnesses & Gas Costs

If the transaction initiator is able to provide enough witnesses beyond ensuring their balance, should the state access be cheaper? This should be deterministic if the witnesses are signed with the transaction, but would add complexity.

Cost of State

How do block proposers and state providers negotiate the price for state? Is it set by the network? Should block proposers tender bids from multiple state providers for a block, and select the cheapest one?

Should the price be set per state access? Per byte of witness data?

If you charge per byte of witness data, how does the BP know the SP isn’t including unnecessary bytes?

If multiple transactions use the same witnesses, should the price be evenly divided? Full price for each transaction? Only the first transaction pays?

State Abstraction

The exact semantics of how execution environments request state is not defined by this proposal, but would be required for the pull or relay models to work.

Decentralized State Network

Instead of collecting transactions and sending the entire bundle to a state provider, would it be possible to create a distributed hash table, and have the block proposer request state on-the-fly during execution? This alternative would block execution of transactions on network requests, and likely make serial execution of transactions too slow/unpredictable. Leveraging advancements in software transactional memory could still make this viable.