Aligning DAO contributions with objectives

In this post, we’re approaching how to align DAO contributions in a setting where a clear goal is already defined.

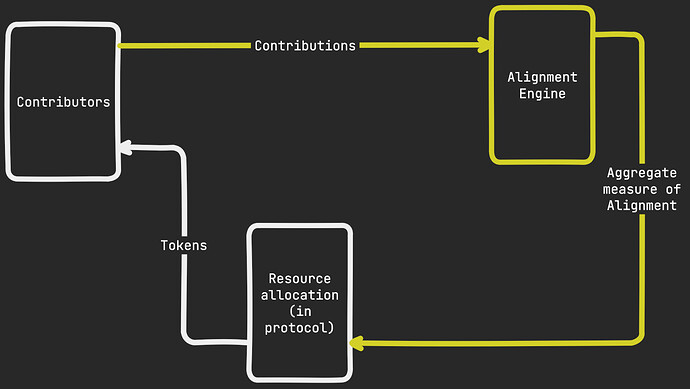

We will define an Objective Alignment Engine (OAE) as a class of mechanisms that fulfill this objective. We aim to define the contour of such mechanisms so that they optimize resource allocation and provide economic guarantees on the efficacy of incentives.

A more complete description along with more concrete examples is available at [r.ag.oae] Objective Alignment Engine.

Motivation

Suppose a DAO where governance contributors are compensated based on a simple rule, like “the top 10 delegates by total votes delegates are paid $10k / month”. As protocol designers, this sounds suboptimal as we have no guarantees that the treasury is spent on the delegates who produce the most useful contributions to governance (e.g. produce the most complete proposals, or vote most consistently). Also, any such rules-based process inevitably becomes gameable under Goodhart’s law.

We’d prefer that contributions were picked individually and reward contributors based on how aligned these contributions are with the overarching goals of the network (e.g., how much are such contributions participating in growth? or decentralization?).

Importantly, we’d also prefer that there is an objective notion of alignment, enabling a mechanism that relies not only on individual preferences but as much as possible on eliciting information (as suggested in this post on mixing auctions and futarchy).

Background

On-chain protocols often struggle to align contributor incentives with network goals. While blockchains are designed to optimize resource spending for security, producing alignment with agreed-upon goals is typically left to external governance systems. OAE mechanisms bring contributions and incentives within the purview of the protocol designer.

This approach aligns with the “skin in the game” and futarchy-like solutions suggested in Moving beyond coin voting governance. We’ll rely on the notion that there is a jury that is incentivized to produce a good judgment of whether contributions are aligned and scale this with additional mechanisms.

Assumptions: objective definition

A central assumption that we take is that the DAO has a clearly defined objective. While this is theoretically difficult to achieve in a decentralized setting, most protocol values and visions are set initially by the core team and steered by a Foundation.

For example, Ethereum focuses today on Scalability, Security, and Sustainability, whereas Optimism has the Superchain vision.

In the rest of this post, we assume an existing process produces a clear definition of an objective o (hence, the Objective part of the Alignment Engine).

The existence of such an objective enables designing mechanisms that rely only on eliciting information from participants, namely whether a contribution is aligned or not with the objective.

Alignment engine

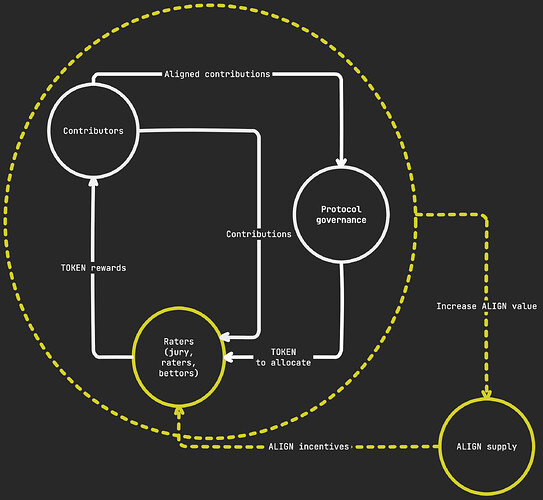

Jury

Once an objective is defined, we want to set up a jury that can review any contribution and evaluate how aligned it is with the objective. This is the central part of this design.

The main function of the jury is to produce ratings “aligned” / “misaligned” on contributions that are produced on the protocol.

To produce alignment within the jury itself, we rely on mechanisms that incentivize truthful reporting but don’t rely on verifiable outcomes (like, BTC/USD quote). Possible such mechanisms are SchellingCoin or self-resolving prediction markets for unverifiable outcomes (Srinivasan et al, 2023).

To enable incentivization and notably negative rewards, we expect jurors to stake tokens ($ALIGN) and receive token emissions as rewards.

Dispute resolution

Here we assume that most contributions can be unequivocally qualified as “aligned” or “misaligned” (ie there is a clear way to rate most contributions, as long as o is well defined).

But equivocal cases will inevitably appear. When a contestable result is produced, a dispute resolution mechanism needs to be enforced (either an external one like a Kleros court or an Augur-style ALIGN token fork).

Calibration

In general, a juror can be an agent making use of any tools available, including AI and prediction markets, to produce the best evaluations. But this leaves open the question of how to incentivize jurors to get better at their jobs so the jury doesn’t degenerate into a static committee.

If part of the contributions have a ground truth to which their ratings can be compared (e.g. growth contributions that aim at increasing a key metric like TVL for a DeFi protocol or fees for an L2), jurors can be rewarded accordingly. This way, the mechanism can still leverage objective outcomes to improve its accuracy (or be calibrated).

Scaling

Armed with such a jury, DAO contributions can theoretically be evaluated. To handle large numbers of contributions, two scaling options are available:

- Prediction markets: bettors predict jury decisions, creating “Aligned” and “Misaligned” tokens.

- Peer prediction: raters evaluate contributions, with a small percentage reviewed by the jury.

Spam protection through staked curation or auctions ensures only valuable contributions are evaluated.

Rewards distribution

With contribution evaluation in place, the last bit is to distribute contribution rewards to incentivize the most aligned contributions to be produced in the future.

Aligned contributions receive rewards from treasury or token emissions, proportional to their alignment rating. Highly aligned contributions may be automatically implemented in proposal-like scenarios

This produces a positive feedback loop where:

- Better-aligned contributions receive more rewards

- This incentivizes more aligned contributions in the future

- The protocol becomes more resistant to misaligned or captured governance over time.

Attacks

Some potential limitations and related attacks include:

- Equivocal objective definition. Attackers may exploit ambiguous objectives to reward misaligned contributions. This can be mitigated by updating the objective when the DAO observes that equivocation happens.

- Jurors collusion and bribing. This can be countered with staking mechanisms, reputation systems, random juror selection, or shielded voting.

- Peer prediction and prediction markets manipulation. Usual caveats and mitigations apply.

Questions

Such OAE mechanisms rely on the existence of an objective o. We haven’t answered how such an objective can be defined in a general setting. There is an argument that leaving it to regular token-voting just pushes the problem around and the overall mechanism inherits some of the issues of both sub-mechanisms. However, it appears that splitting the problem in two has benefits, as, once an objective is defined, more deterministic outcomes can be achieved through mechanism design.

Also, other kinds of mechanisms can be devised that rely on subjective evaluations. Including subjective evaluations might render objective definition superfluous. But relying on a jury whose jurors input their own preferences leaves the question open of how the jury achieves legitimacy. A solution would be to rely on a measure of juror reputation, as pioneered by Backfeed.