tl;dr We propose dynamic penalties as an improvement of the current ePBS design. On average, penalties for failed payloads would be small so that honest builders are not harmed much by them, but penalties escalate in case of high failure rate. Dynamic Penalties can be combined with static rewards for delivered payloads to enhance their performance. They prevent free option exercise in all but the most extreme cases. We provide a detailed implementation proposal of dynamic penalties.

Joint work with @BrunoMazorra. Thank you to @potuz for discussions. Thank you to Leo Arias and @tripoli for extensive feedback on a draft.

As has been documented in 1, 2 and 3 the free option problem, if un-mitigated, could severely deteriorate the user experience of Ethereum post Glamsterdam. In 3 we have looked into different mitigation mechanisms, in particular we have argued that

-

shortening the time window between the PTC deadlines would be very effective in mitigating the problem, but would eliminate some or most of the scaling advantage that we want to achieve from ePBS.

-

penalties for failures to deliver payloads and/or blobs would be effective in most cases, provided that penalties are sized correctly.

-

Static penalties would be either ineffective or too large.

-

Conditioning penalties on bids or fees would be ineffective, as bids and fees are too noisy of a signal and make the policy possibly game-able.

-

Escalating penalties with the number of failed payloads, would be most effective and provide small penalties on average that wouldn’t harm honest builders too much, while deterring option exercise in all but the most extreme cases.

-

Besides shortening the time window and penalties,

- rewards for delivered payloads would have a similar effect as penalties. Dynamic rewards have, however, the downside that they are game-able by builders. Combining static rewards with dynamic penalties would be a suitable policy without this downside and could be easily implemented (see below).

In this document we want to describe a concrete implementation of dynamic penalties based on failed execution payloads.

The policy has the following features:

-

Failure to publish blobs and/or an execution payloads in time is penalized. Failures are determined by the result of the PTC vote, i.e. a penalty for slot t is due if an execution payload for slot t is unavailable but a valid commitment is there.

-

The size of the penalties are set by a dynamic rule that we describe in detail below. Under the rule, correlated failures are punished much more severely than isolated failures.

-

Penalties are processed at the end of the following epoch together with pending builder payments.

Possible issues

Our proposal is not totally cost free for honest builders as unintentional payload delivery failures can very rarely happen. However, it should not impose significant cost on them and is much less intrusive than missed slot penalties would be. Note that a self-building validator can always release the payload at the same time as the commitment to it. This will make them almost surely avoid missed payload penalties. A builder that is not the proposer can release the payload as soon as they learn that the bid is accepted, which is slightly more prone to failure and therefore risky for them. Our dynamic policy guarantees, however, that penalties are small on average, so that in the average case a honest participant is not hurt much even when missing a payload. In the happy path, penalties work well and do not escalate so that the worst case is close to the average case.

If possible changes in rewards for validators are a concern (although we believe that their failure rates will be negligible), we can combine penalties with static rewards for delivering payloads as we further describe below.

Another possible issue is that builders could change their behavior for additional margin of safety in case penalties are temporarily high: while it seems unlikely that proposers intentionally will miss slots to avoid penalties (which would them make forego CL rewards and EL rewards and MEV), it might be that builders build payloads differently temporarily. E.g. it is conceivable that they temporarily will not include blobs, in case blob delivery is more error-prone than delivering payloads without blobs. However, we believe that such changes in behavior if at all an issue would be only temporary in the rare case of severely escalated penalties.

Finally, we have to think about possible attacks where an adversary delays messages to trigger missed payloads. While we have not done a careful analysis of this scenario yet, our intuition is that this is already an issue without penalties (as missing a payload harms a builder by letting them forego rewards) and the introduction of penalties would make it only marginally worse.

Policy and backtest

Let \alpha\in(0,1) denote the tolerated failure rate, i.e., a desired upper bound on the fraction of rounds in which the payload is empty and let

y_t = \mathbf{1}\{\text{payload for slot } t \text{ is committed but un-available} \}.

We define the dynamic penalty mechanism with tolerated failure rate \alpha, step-sizes \eta_t measured in ETH, min penalty p_{min} and maximum penalty p_{max} both measured in ETH:

Dynamic Penalty mechanism with state variable p_t

Parameters: (\alpha, \eta_t, p_{\min}, p_{\max}).

Initialize p_1 \leftarrow p_{\min}.

For each slot t:

- Observe y_t.

- Set g_t \leftarrow \alpha - y_t.

- Update p_{t+1} \leftarrow \min\bigl\{ p_{\max}, \; \max\{ p_{\min}, \; p_t - \eta_t g_t \} \bigr\}.

A constant step size \eta defines a number of slots T=1/\eta^2 and vice versa a number of slots T defines a step size \eta = 1 /\sqrt{T} with the interpretation that the failure rate \alpha is guaranteed on average over each T slot period.

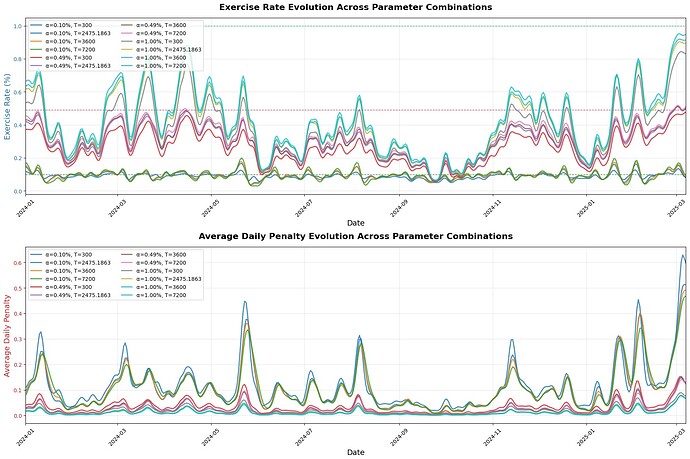

For a theoretical analysis and regret guarantees of the policy see the paper. We have backtested the algorithm between 2024-01 and 2025-03 (see paper for methodology), obtaining robustness of the algorithm with different pairs of parameters. The backtested results align with the theoretical no-regret guarantees established in the paper.

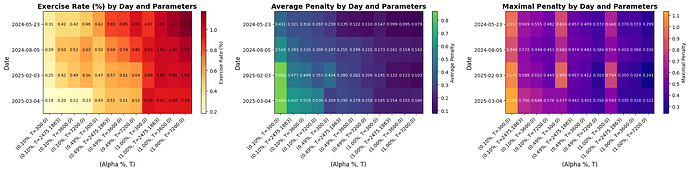

The parameters \alpha and T play distinct conceptual roles. \alpha is the acceptable fraction of failed payloads. The smaller \alpha is, the less frequently block builders will have incentives to exercise the option, but the higher the resulting dynamic penalty. By contrast, T is the time window over which this average is evaluated. The smaller T is, the more abruptly the dynamic penalty is updated—potentially allowing it to react quickly on volatile days, but at the cost of being overly reactive on average. While the choice of \alpha primarily reflects the desired properties of the mechanism, T must be chosen to match typical market conditions. However, in our dataset we find that different reasonable choices of T (e.g., the number of blocks in one hour, six hours, one day, etc.) lead to broadly similar outcomes. In short, at least for CEX-DEX arbitrage, the autocorrelation over the previous 300 blocks is sufficient to estimate the average value of the free option. For example, we observe that when \alpha = 0.1\%, the exercise rate, mean penalty, and median penalty remain nearly unchanged across reasonable choices of T, while the maximum penalty increases noticeably and the variance of the penalty grows as T becomes smaller. For a more detailed comparison, see the following table.

| α (%) | T | Step Size | Exercise Rate (%) | Mean Penalty | Median Penalty | Max Penalty | Std Penalty |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.10 | 300 | 0.06 | 0.09 | 0.13 | 0.08 | 1.14 | 0.16 |

| 0.10 | 2475 | 0.02 | 0.10 | 0.11 | 0.08 | 0.71 | 0.12 |

| 0.10 | 3600 | 0.02 | 0.10 | 0.11 | 0.08 | 0.65 | 0.11 |

| 0.10 | 7200 | 0.01 | 0.10 | 0.11 | 0.09 | 0.58 | 0.10 |

| 0.49 | 300 | 0.06 | 0.27 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.91 | 0.07 |

| 0.49 | 2475 | 0.02 | 0.30 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.47 | 0.05 |

| 0.49 | 3600 | 0.02 | 0.31 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.44 | 0.05 |

| 0.49 | 7200 | 0.01 | 0.32 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.38 | 0.04 |

| 1.00 | 300 | 0.06 | 0.38 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.79 | 0.05 |

| 1.00 | 2475 | 0.02 | 0.42 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.42 | 0.03 |

| 1.00 | 3600 | 0.02 | 0.43 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.38 | 0.03 |

| 1.00 | 7200 | 0.01 | 0.45 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.33 | 0.03 |

Moreover, on four extreme volatility days, penalties work quite well. Exercise rates and penalties on these days for different parameters are as follows:

Note that on highly volatile days, a small T increases penalties fast enough to reduce the exercise rate for that day. However, it does so by rapidly escalating the penalty.

As a general take away, penalties with step size in the range of 0.01-0.06ETH which, in our data set, yields average penalties of 0.01-0.04 ETH would be effective. Note that this is around the same order of magnitude as beacon block proposal rewards.

Implementation details

Next, we describe an implementation of the policy in the current Gloas specs with the aim to keep modifications minimal.

We need to introduce three new presets:

| Name | Value |

|---|---|

PENALTY_STEP_SIZE |

Gwei(2*10**7) (= 20,000,000) |

PENALTY_DOWN_STEP_SIZE |

Gwei(10**5) (= 100,000) |

MAX_PENALTY |

Gwei(2^3*10**9) (= 8,000,000,000) |

The previous PENALTY_STEP_SIZE and PENALTY_DOWN_STEP_SIZE were determined by considering \alpha =1/201\approx 0.49\% and T\approx 2475. As shown in the previous table, this parametrization yields a failure rate of 0.3% and a mean penalty of 0.03ETH, while keeping the maximal observed penalty relatively small at 0.47ETH. Other preset values would of course be possible, e.g. if a higher failure rate is acceptable.

We also need to introduce a new state variable that keeps track of the size of the current missed payload penalty.

class BeaconState(Container):

...

# [New in EIP7732]

execution_payload_availability: Bitvector[SLOTS_PER_HISTORICAL_ROOT]

# [New in EIP7732]

+ missed_payload_penalty: Gwei

# [New in EIP7732]

builder_pending_payments: Vector[BuilderPendingPayment, 2 * SLOTS_PER_EPOCH]

# [New in EIP7732]

builder_pending_withdrawals: List[BuilderPendingWithdrawal, BUILDER_PENDING_WITHDRAWALS_LIMIT]

# [New in EIP7732]

latest_block_hash: Hash32

# [New in EIP7732]

latest_withdrawals_root: Root

The penalty would be initialized to 0 Gwei in the fork logic. We update the penalty size during process_execution_payload_bid().

Missed payloads are implicitly tracked through pending payments in the current EIP7732 specs. Note that in the current specs a pending payment for a slot is processed each time a payload is processed for the slot. Thus, all pending payments that are processed at the end of an epoch are payments for failed payloads.

There are different ways to record pending penalties, a simple one is to just add another attribute to the BuilderPendingPayment Container:

class BuilderPendingPayment(Container):

weight: Gwei

# records the size of a pending penalty

+ penalty: Gwei

withdrawal: BuilderPendingWithdrawal

We need to modify the process_execution_payload_bid function and epoch processing to record penalties and to deduct them from balances. There are many different ways of doing this. We propose to record a penalty each time an execution payload bid is processed. If the corresponding payload is delivered, the penalty is just ignored (and set back to 0) when processing payments within process_execution_payload (which needs no modification). If the corresponding payload is not delivered, the penalty is processed at the end of the next epoch. Note furthermore that we need to issue a “payment” also for 0 bids to keep track of penalties for self-builders. The 0 payment is actually never processed itself, but only the penalty if needed.

There are some subtleties that have to do with the asymmetry between self-builder and builder penalties, as self-builders have “limited liability” in the highly unlikely edge-case that they propose multiple times in two consecutive epochs and penalties are exceptionally high during these epochs. We comment on these subtleties further below.

def process_execution_payload_bid(state: BeaconState, block: BeaconBlock) -> None:

signed_bid = block.body.signed_execution_payload_bid

bid = signed_bid.message

builder_index = bid.builder_index

builder = state.validators[builder_index]

amount = bid.value

# For self-builds, amount must be zero regardless of withdrawal credential prefix

if builder_index == block.proposer_index:

assert amount == 0

assert signed_bid.signature == bls.G2_POINT_AT_INFINITY

else:

# Non-self builds require builder withdrawal credential

assert has_builder_withdrawal_credential(builder)

assert verify_execution_payload_bid_signature(state, signed_bid)

assert is_active_validator(builder, get_current_epoch(state))

assert not builder.slashed

# determine missed payload penalty for the current slot

+ if is_parent_block_full(state):

+ penalty=max(0,state.missed_payload_penalty-PENALTY_DOWN_STEP_SIZE)

+ else:

+ penalty=min(MAX_PENALTY,state.missed_payload_penalty+PENALTY_STEP_SIZE)

# Check that the builder is active, non-slashed, and has funds to cover the bid and penalties

- pending_payments = sum(

- payment.withdrawal.amount

- for payment in state.builder_pending_payments

- if payment.withdrawal.builder_index == builder_index

- )

+ pending_payments = 0

+ pending_penalties = 0

+ for payment in state.builder_pending_payments:

+ if payment.withdrawal.builder_index == builder_index:

+ pending_payments += payment.withdrawal.amount

+ pending_penalties += payment.penalty

+ future_penalties = proposer_lookahead[bid.slot % SLOTS_PER_EPOCH + 1 :].count(builder_index) * MAX_PENALTY

pending_withdrawals = sum(

withdrawal.amount

for withdrawal in state.builder_pending_withdrawals

if withdrawal.builder_index == builder_index

)

assert (

amount == 0

or state.balances[builder_index]

- >= amount + pending_payments + pending_withdrawals + MIN_ACTIVATION_BALANCE

+ >= amount + pending_payments + pending_withdrawals + pending_penalties + penalty + future_penalties + MIN_ACTIVATION_BALANCE

)

# Verify that the bid is for the current slot

assert bid.slot == block.slot

# Verify that the bid is for the right parent block

assert bid.parent_block_hash == state.latest_block_hash

assert bid.parent_block_root == block.parent_root

assert bid.prev_randao == get_randao_mix(state, get_current_epoch(state))

# Record the pending payment and penalty

- if amount > 0:

- pending_payment = BuilderPendingPayment(

- weight=0,

- withdrawal=BuilderPendingWithdrawal(

- fee_recipient=bid.fee_recipient,

- amount=amount,

- builder_index=builder_index,

- withdrawable_epoch=FAR_FUTURE_EPOCH,

- ),

- )

- state.builder_pending_payments[SLOTS_PER_EPOCH + bid.slot % SLOTS_PER_EPOCH] = (

- pending_payment

- )

+ pending_payment = BuilderPendingPayment(

+ weight=0,

+ penalty=penalty,

+ withdrawal=BuilderPendingWithdrawal(

+ fee_recipient=bid.fee_recipient,

+ amount=amount,

+ builder_index=builder_index,

+ withdrawable_epoch=FAR_FUTURE_EPOCH,

+ ),

+ )

+ state.builder_pending_payments[SLOTS_PER_EPOCH + bid.slot % SLOTS_PER_EPOCH] = (

+ pending_payment

+ )

# Cache penalty

+ state.missed_payload_penalty = penalty

# Cache the signed execution payload bid

state.latest_execution_payload_bid = bid

The tracking of possible future penalties using the proposer_lookahead function is there to guarantee that a builder who was also selected as a proposer in the current or next epoch can cover their bid even if they self-build when proposing in the future and being penalized then. Instead of MAX_PENALTY, we could require the max possible penalty during the lookahead window here which might be smaller.

At the end of the next epoch after the epoch in which the payload was not delivered, we process the penalty and remove it from circulation.

def process_builder_pending_payments(state: BeaconState) -> None:

"""

Processes the builder pending payments from the previous epoch.

"""

quorum = get_builder_payment_quorum_threshold(state)

for payment in state.builder_pending_payments[:SLOTS_PER_EPOCH]:

if payment.weight > quorum:

+ if payment.penalty>0:

+ decrease_balance(state,payment.withdrawal.builder_index,payment.penalty)

amount = payment.withdrawal.amount

+ if amount > 0:

exit_queue_epoch = compute_exit_epoch_and_update_churn(state, amount)

withdrawable_epoch = exit_queue_epoch + MIN_VALIDATOR_WITHDRAWABILITY_DELAY

payment.withdrawal.withdrawable_epoch = Epoch(withdrawable_epoch)

state.builder_pending_withdrawals.append(payment.withdrawal)

old_payments = state.builder_pending_payments[SLOTS_PER_EPOCH:]

new_payments = [BuilderPendingPayment() for _ in range(SLOTS_PER_EPOCH)]

state.builder_pending_payments = old_payments + new_payments

There are some quirks in our implementation that we want to comment on (and could probably be avoided with other implementations, at the cost of possibly introducing other quirks):

The implementation treats self-builders and other builders slightly asymmetrically: whenever a builder bid is made, we check whether the builder can cover the bid and has a post bid balance of at least 32ETH, even after all pending payments and pending/possible penalties are deducted. In contrast, a proposer can always self-build independently of their balance. In a highly highly unlikely edge case, a proposer proposes multiple times in two consecutive epochs and penalties are exceptionally high during these epochs so that after deducing several penalties from the proposer balance, it would not be enough to fully cover the next penalty. Effectively that introduces limited liability for self-builders for penalties, but only in scenarios that have vanishingly small probability to ever happen with the current MaxEB settings. As this is an unlikely edge case (with limited consequences even if it would happen) we don’t think that it needs to be addressed. However, there would be ways to address it if desired, e.g. by not allowing proposers to self-build if their post-penalties balance is too low.

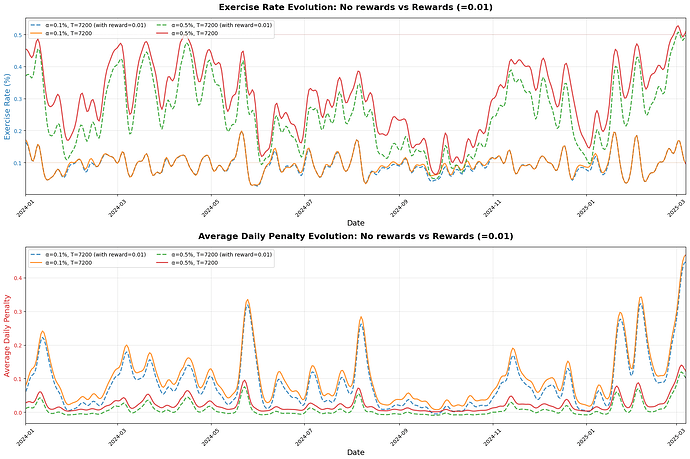

Rewards

The dynamic penalties can be combined with static rewards for delivered payloads. As we can see in the following figure, this has at least two advantages:

-

Combining penalties with rewards is likely perceived fairer by validators, in comparison to pure penalties that can be perceived to be a policy entirely at their expense.

-

It decreases the average penalties (but not really the worst case penalties) needed to sustain a particular payload delivery rate.

The obvious disadvantage is that they lead to additional issuance or rewards for other duties need to be decreased.

The implementation of static rewards is straightforward: builder balance can be increased by the fixed reward each time that process_execution_payload() is called.

Conclusion

We think that dynamic penalties can be an effective means to mitigate the free option problem and to guarantee a high rate of payload delivery in many different regimes. The obvious caveat is that it will not prevent option exercise to be profitable in the most extreme cases. Since the damage in these extreme cases is arguably particularly high (under extreme volatility, placing transactions in blocks tends to be particularly valuable), even less than 0.5% of failed payloads can create considerable welfare loss if occurring at the wrong times, when they are particularly likely. However, without any mitigation mechanism the problem would be even more severe. Moreover, as exploiting the free option requires some amount of preparation by builders (e.g. by adding private blobs to the payload), it could be that introducing penalties will prevent many builders to refrain from using the free option in their strategy at all, and thus in particular they will not be in the position to exploit it in the rare occasions when it is profitable.

Besides mitigating the free option problem, introducing penalties can have additional benefits: inclusion lists combined with incentives to deliver payloads can give stronger censorship resistance guarantees. Penalties also remain a useful feature in a possible future where an APS design replaces the current proposer selection mechanism, as high payload delivery rates remain a desirable protocol outcome.

Billionaire Warren Buffett said it best of course: