Vivian Zhu, Otakar Korinek, Alex Duckworth - February 3, 2025

1. Introduction

This research was funded by cyber•Fund and conducted by members of FranklinDAO, a blockchain organization run by students from the University of Pennsylvania. The focus of the research was to analyze the proposal focused on reducing the issuance of ETH by Ethereum to Ethereum validators. The effects of this proposal would directly impact stakers and market participants who benefit from the staking yield. Therefore, we explored the literature in depth and also conducted interviews with participants at different levels of staking sophistication and market participation. The breakdown of interviews consists of 1-4 interviewees from largest players in each of the key actors in eight categories we have broken down – Solo Stakers, Large Crypto holders / Digitally Native Individuals, Retail Investors, Institutions / High Net Worth Individuals, SSPs, Staking Pools, Centralized Actors, and Distributed Validator Technology.

2. Overview of ETH staking

The transition of Ethereum from a Proof-of-Work (PoW) to a Proof-of-Stake (PoS) consensus mechanism marked a significant evolution in Ethereum’s history. This shift was driven by the need for enhanced security, greater decentralization, and more efficient energy usage. In PoS, validators replace miners, securing the network by staking their ETH. Validators are chosen to propose and attest to blocks, earning rewards or facing penalties based on their performance. The requirement to stake 32 ETH to become a validator ensures a robust commitment to the network’s security and functionality, while the separation of layers—the consensus layer (CL) and execution layer (EL)—facilitates efficient communication and coordination within the blockchain.

Deposits and withdrawals play a crucial role in maintaining the PoS consensus. Deposits are used to create or top up validators, ensuring they can participate effectively in securing the network. Withdrawals, whether partial or full, allow validators to reclaim their staked ETH, providing flexibility and incentivizing continued participation. The introduction of withdrawal mechanisms, initially met with skepticism, has proven effective in enhancing Ethereum’s resiliency and encouraging validator diversity. This flexibility has increased the number of validators and integrated staking into the broader DeFi ecosystem, leading to innovations like Liquid Staking Tokens (LSTs) and restaking.

3. Overview of ETH issuance proposal

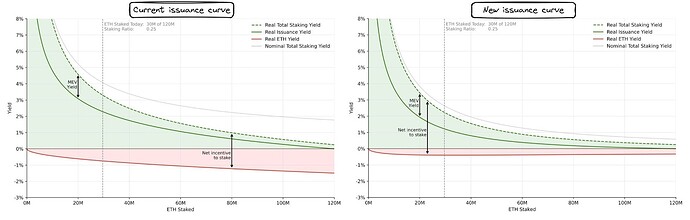

The proposal suggests a new reward curve that gradually reduces issuance as the amount of staked ETH increases. This approach aims to balance the incentives for staking with the need to keep the network secure without over-rewarding validators. By tempering issuance, Ethereum can ensure that staking remains attractive while preventing excessive accumulation of control by a few entities. The paper asserts that the adjustment is crucial for the long-term sustainability and robustness of the Ethereum network. For a more detailed discussion of the proposal, please refer to Caspar’s writeup here.

4. Interviews

In the paper, we will reference interviews conducted with each stakeholder listed. Our interviewers have requested to remain anonymous, so we have created the descriptions accordingly:

[1] Interview conducted with Nixo from the EthStaker community

[2] Interview conducted with P2P

[3] Interview conducted with a large crypto holder

[4] Interview conducted with a founder of liquid staking derivative startup

[5] Interview conducted with Coinbase Investor Relations team

[6] Four interviews conducted with university students in blockchain space

[7] Interview conducted with a hedge fund

[8] Interview conducted with Chorus One

[9] Interview conducted with Lido

[10] Interview conducted with Obol

5. Key findings

Areas of investigation

Our research has focused on key actors and firms across the Ethereum staking landscape. We have conducted interviews and analyzed data to understand the potential effects of the proposed issuance changes on various stakeholders. Definitions of each stakeholder will be discussed in their individual sections.

Effects on stakers

Solo Stakers:

- Most vulnerable to changes in the issuance curve

- Supportive of adjustments that favor decentralized staking

- Concerned about potential negative issuance and declining real yields

- Face challenges with tax implications, especially when nominal yields don’t reflect real economic gains

Large Crypto Holders / Digitally Native Individuals:

- Primarily interested in ETH for price appreciation

- View staking as a secondary benefit

- Prefer liquid staking tokens (LSTs) for DeFi utility

- Relatively insensitive to small yield changes due to convenience and gas fee considerations

Retail Investors:

- Generally “sticky” customers, prioritizing convenience and brand trust

- Often indifferent to short-term price fluctuations or minor yield differences

- Willing to stake on platforms like Coinbase despite potentially lower yields

Institutions/High Net Worth Individuals:

- Prioritize security, compliance, and dilution protection

- Demand for staking is relatively inelastic

- Willing to accept lower yields (even as low as 1%) for the benefits of staking

Changes in distribution amongst staking entities

Staking Service Providers (SSPs):

- Larger SSPs may be better positioned to weather reduced yields due to economies of scale

- Smaller SSPs likely to face more significant challenges, potentially leading to industry consolidation

- May need to cut costs, particularly in engineering and infrastructure

Staking Pools (e.g., Lido):

- May face some compression in fees proportionate to the decline in ETH yield

- Expected to continue innovation efforts, supported by substantial treasury reserves

Centralized Exchanges (e.g., Coinbase):

- Staking flows expected to remain steady due to prioritization of security and ease of use by customers

- Potential for increased centralization raises concerns about network security (e.g., 51% attack risk)

- Plans to continue operations, subsidized by profits from other parts of the business

Distributed Validator Technology (DVT):

- Faces significant challenges with reduced issuance rates

- May struggle to maintain profitability, potentially undermining decentralization goals

- Exploring strategies to remain viable, including fee structure changes and efficiency improvements

6. Profiling the key actors in the space

In simplest terms, the staking landscape can be divided into those who supply ETH and those who take in ETH “deposits” and use them to participate in validating the network. We detail both segments below.

Staked ETH Suppliers

Solo Stakers

Solo stakers supply ETH into their own validators, which are participants in the Ethereum network that work with a group of validators to verify transactions together. They are necessarily tech-savvy, allowing them to run their own infrastructure. They need to setup the validator nodes, install all necessary software for transaction processing and validation rules, and maintain their infrastructure.

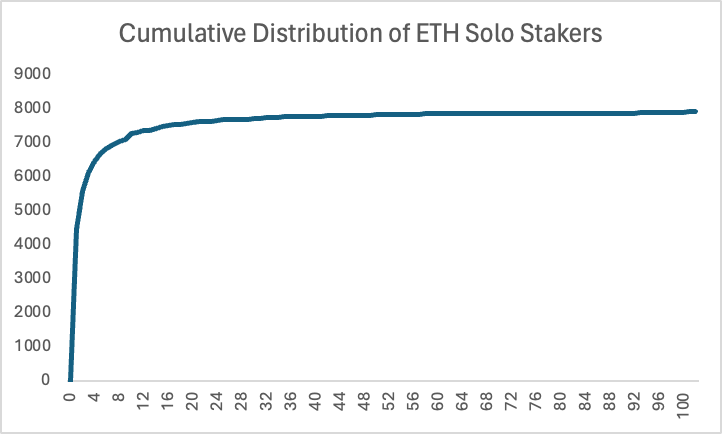

Individual solo stakers are intermediate in size amongst the “ETH suppliers.” Based on data from Rated Network, the average solo staker has 4.5 validator nodes running and the largest solo staker has 201 validator nodes. The median, though, sits at 1 validator node. That means most solo stakers have ~32 ETH staked, translating to roughly $125,000 – a sizable investment.

In terms of solo stakers share of the ETH supplied, it’s fairly low. Rated estimates that they form 6.5% of the network. Nevertheless, solo stakers form a larger portion of the “voice” within the community because they contribute most to decentralization of the network.

The most pressing concern that solo stakers face is that they are finding themselves becoming more irrelevant to ongoing protocol changes in the rapid expansion of staking protocols and centralized exchanges. Since the minority of validators belong to solo stakers, they are put into a challenging position with less representation as most other validators in the network belong to professionals [1]. Researchers and other actors have attempted to represent or advocate for solo stakers, however they have not been able to make a concrete impact with actionable results.

Preferences

In addition to the ETH, solo stakers must purchase the hardware capable of validating the network. That cost typically amounts to $1,000. The operating costs of solo-staking are thus minimal. The only substantial costs, both monetary and time-wise, are the startup costs. The startup costs are sunk for existing solo stakers. Running the validator itself requires little to no cost and time commitment.

Solo staking offers lower ROI than liquid staking due to startup infrastructure costs, their security setup, and the inability to use a liquid token. The tradeoff is added security – solo stakers don’t need to worry about the integrity of the liquid staking protocol. Perhaps a more important benefit of solo staking is the “altruistic” gain from securing the network as was originally intended and contributing to decentralization.

From an economic perspective, the primary concern for solo stakers is negative issuance, where the total supply of tokens actively decreases over time, as they are the most significantly affected group. Solo stakers are particularly vulnerable because they lack the resilience and buffer that professional staking services possess, making it harder for them to endure prolonged periods of financial strain.

Insights

Solo stakers are receptive to changes in the issuance curve.

Solo stakers are particularly sensitive to changes in the issuance curve. A significant portion of solo stakers dislike issuance reduction in general, but expressed support for adjustments to the issuance curve if such changes would favor decentralized forms of staking. This would be more advantageous for solo stakers, however, is unlikely to be implemented, as it may take approximately four to five years of research and development to complete [1]. Additionally, implementing such changes will be challenging if those who benefit the most from the current issuance curves, such as venture capitalists with significant investments, oppose them.

The current risk for solo stakers lies in the potential for the issuance curve to reach 100% staked, resulting in a yield of just 1.8%. This yield is considerably low, making it difficult for solo stakers to remain competitive unless they have access to advanced technology. As it stands, the current issuance curve is particularly challenging for solo stakers, who lack the resources and buffers available to professional staking services.

Price elasticity

A decision-making that’s not purely economic combined with the sunk costs makes solo stakers relatively sticky. That’s corroborated by our interviews with Nixo from the EthStaker community. However, we question how sensitive are “inflows” – e.g. does the number of new stakers depend on the yield they can get.

According to P2P, most solo stakers invested in Ethereum a long time ago and are not primarily motivated by financial gains. Their participation is often rooted in a deep belief in the Ethereum network and its potential. The cost of running the necessary infrastructure for staking is significant, with fixed costs for setting up a node amounting to approximately $1,500 [2]. Given the current price of ETH, solo staking is frequently not profitable, underscoring that these individuals are driven by idealistic rather than economic motivations.

Taxes

One of the most significant pain points for solo stakers is the disparity between real and nominal yields. When solo stakers receive nominal yields that do not reflect the true economic gains due to inflation or other factors, they still face tax liabilities based on these nominal figures. This situation becomes particularly painful when stakers are taxed on nominal yields without realizing any real financial benefit. Essentially, they end up paying taxes on “nothing,” as the nominal gains do not translate into actual income.

Taxes represent the second biggest issue for solo stakers, who often face unfair or unclear tax treatment depending on their country of residence. In Germany, the tax situation for staking is favorable, providing a supportive environment for solo stakers. In contrast, Austria has a less favorable tax regime, making it more challenging for stakers. In the USA, the tax treatment of staking is inconsistent and often leaves participants guessing, with some instances being advantageous and others not.

As the staking ratio increases over time, this problem is exacerbated. The real yield for stakers declines faster than the nominal yield, further intensifying the tax burden on solo stakers. This declining real yield, combined with unfavorable tax treatment, creates a challenging financial environment for solo stakers, making it difficult for them to sustain their participation in the staking ecosystem. Addressing these tax issues is crucial for creating a more equitable and supportive environment for solo stakers.

Attitudes on existing advocacy for solo stakers

In the Staking Survey 2024 conducted by EthStaker with 1024 responses, of which 868 respondents consist of stakers who claim to control their node’s configuration, a notable 19% of respondents believe researchers overlook solo Ethereum stakers, possibly due to the topic’s limited discussion and the prevalence of professional validators. Reducing returns to scale seems impractical, especially since larger entities can masquerade as solo stakers, further complicating the issue and potentially skewing perceptions of network participation.

Large Crypto holders / Digitally Native Individuals

This segment largely supplies their ETH into decentralized pools like Lido and RocketPool. By definition, these people are digitally native, have their own wallets, and feel comfortable navigating the blockchain. That removes perhaps the largest barrier to entry to decentralized pools for retail: knowing how to get your money there.

Preferences

Staking is a secondary concern for this segment, just like for most. Based on our interviews, techies are primarily interested in ETH due to the price appreciation component. Staking adds a little extra return with little downside.

Techies prefer staking pools due to the ability to use the liquid staking tokens (LSTs) in DeFi. In their words, they “most likely wouldn’t stake if they wouldn’t get an LST, as the yield is lower than they can get on Aave.” [3] That allows them to maximize the utility of their staked tokens. They are also wary of the time commitment solo staking requires / do not have the requisite amount of ETH.

Insights

For this segment, price elasticity plays a crucial role in their staking behavior. While staking is a secondary concern, large crypto holders and digitally native individuals are motivated by the additional returns it provides. They are not devoted to staking, but they don’t want to unstake primarily due to the hassle and gas fees associated with moving their funds elsewhere. The ease of use and liquidity offered by platforms like Lido, which has integration with DeFi applications, further reinforce their decision to remain staked, even in the face of lower yields.

The primary motivators for these individuals include potential airdrops associated with staking and the opportunity to capitalize on higher APY opportunities through staking or restaking. These incentives drive their participation in staking, despite the relatively low yields compared to other DeFi opportunities.

The sentiment expressed by these individuals highlights their pragmatic approach to staking. They are primarily motivated by convenience and the added utility of LSTs in DeFi, rather than the staking yield itself. As one interviewee mentioned, “If yield falls, I would keep it there—hassle not worth it plus gas” [4]. This reflects a general preference for maintaining the status quo due to the complexities and costs associated with moving staked assets. Lido’s extensive liquidity and broader DeFi applications further solidify this preference, making it the platform of choice for digitally native individuals looking to maximize the utility of their staked ETH.

Retail Investors

Retail investors constitute a significant portion of Ethereum stakeholders, though their ETH holdings typically form a minimal part of their overall investment portfolio. According to ByBit May 2024 data, only about 9% of retail crypto assets are invested in ETH. This suggests a diverse approach to cryptocurrency investment among retail participants, with Ethereum being just one component of a broader strategy.

Preferences

The preferences of retail investors in the Ethereum ecosystem are noteworthy. As observed by Coinbase’s Investor Relations team, “by and large, simple customers tend to be more of a staker” [5]. In addition to interviews conducted with university students active in the blockchain space, we conclude that retail investors are often comfortable with long-term holding strategies and don’t typically face immediate liquidity constraints [6]. Their willingness to stake suggests a belief in Ethereum’s long-term potential and a desire for passive income through staking rewards.

Insights

When it comes to price elasticity, retail investors in Ethereum demonstrate interesting behaviors. Many seem relatively indifferent to short-term price fluctuations or minor differences in staking yields. Their primary motivation appears to be holding ETH for long-term price appreciation rather than maximizing short-term gains. This is evidenced by the fact that many retail investors stake on platforms like Coinbase, which may offer up to 25% lower yields compared to alternatives [5]. The reasons for this preference include ease of use, perceived trustworthiness, and possibly a lack of awareness or concern about yield differences. This behavior suggests that retail ETH investors are generally “sticky” customers, prioritizing convenience and brand trust over marginal gains in staking rewards.

Institutions/High Net Worth Individuals

Preferences

Institutions and high-net-worth individuals prioritize security above all else, as losing clients’ money would have significant repercussions for their entire operation [7]. Compliance is also critical, ensuring accurate tax reporting and adhering to regulations when allocating client funds. Another key concern is dilution protection, as holding plain ETH is inherently dilutive—staking offers a way to mitigate this. A paper by Steakhouse Financial highlights that stakers, including institutions, face various barriers, but staking is essential to protect against the dilution of their ETH holdings. Due to these preferences, institutions primarily rely on centralized solutions for staking.

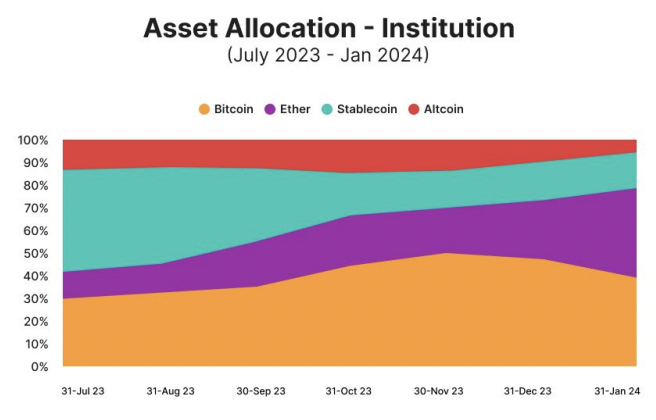

Institutional staking is substantial. According to Coinbase’s Investor Relations reports, over $10.9 billion worth of assets were staked by institutional customers (we use FY’23 disclosure and raise it by change in ETHs price). By applying the percentage of ETH assets on Coinbase’s platform, this translates to roughly $3.4 billion of ETH staked, or about 0.9 million ETH. The allocation of ETH by institutions continues to rise.

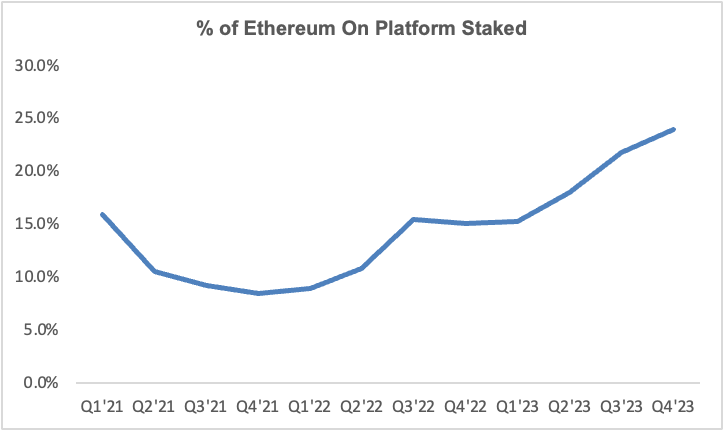

Source: ByBit

Insights

Institutional demand for staking is inherently inelastic. Yield is a secondary concern, with the primary focus on allocating ETH for clients. Institutional ETH holdings on platforms like Coinbase are significant, with only 24% of ETH currently staked. Based on insights from Coinbase Investor Relations, the percentage of institutional ETH staked is likely lower than the aggregate. Assuming that 20% of institutional ETH on Coinbase is staked (vs. 24% platform-wide average), yields approximately $15 billion of institutional ETH staked on the Coinbase platform.

From our conversation with P2P, institutions would value even a 1% yield, indicating that demand for staking will persist [2]. The competition between different staking providers is not primarily based on yield but on the additional services they offer.

Staking Providers

Solo stakers also fit into this category, but they have been discussed separately.

SSPs

Staking Service Providers (SSPs) are actors who provide custodial or non-custodial staking services, which lower barriers to entry by handling technical complexities, provide more rewards through strategies and optimal infrastructure, protect against slashing, and data analytics. Specifically, in this paper, we are referring to companies such Chorus One, which provides quick staking integrations for institutions and investors, research, and protocol support.

Cost Structure

For SSPs, costs increase marginally with each additional validator until they reach around 500 validators, after which they benefit from economies of scale. The primary costs are infrastructure-related, followed by personnel expenses. With MVI, SSPs earn lower margins but remain profitable.

Taking Chorus One as a unit economics example, about 80-90% of their costs are fixed, with the rest being variable. The fixed costs mainly involve backend operations, particularly engineering staff, which make up the largest portion. Engineers are needed to manage a certain number of servers, and as the number of machines grows, so does the need for “engineer hours,” making these costs semi-fixed. Node operators/SSPs can reduce some costs by cutting redundancies and administrative expenses, but these savings are marginal. Additional fixed costs include self-hosting, OVH, and maintaining a research team [8].

Variable costs primarily involve servers, where some economies of scale are present. However, some costs, like accounting and finance, remain constant no matter the activity level, while most engineering salaries are semi-variable. They remain mostly constant, but, at a certain point, the SSP needs to invest incremental resources in them. The variable costs are more directly tied to the number of servers needed [8].

Sources of Staked ETH

There are two primary sources of staked ETH, each with different customer bases but similar motivations—price upside is the main concern, with staking as a secondary objective [8].

Category 1: Lido and Liquid Staking

The component of ETH staked through Lido and liquid staking solutions is relatively insensitive to staking yield due to the lower opportunity cost and strong network effects. Many users opt to stake simply because they can, regardless of whether the yield is 1%, 2%, or 3%. This side of the business has seen significant growth, with liquid staking tokens (LSTs) increasing in popularity. However, the share of LSTs in the market has been decreasing as SSPs ramp up direct sales.

Category 2: Direct Staking by High-Net-Worth Individuals (HNW), Institutions, and Intermediaries

This category includes those who hold ETH primarily for price appreciation and choose to stake it, often using an SSP’s API or DIEP (a smart contract for staking) to capture a fraction of the rewards. Direct stakers prefer SSPs due to lower risks and compliance benefits. These stakers are typically long-term holders, parking their capital to earn additional yield without taking on smart contract risks associated with liquid staking providers. They view direct staking as a relatively risk-free way to earn some yield on their crypto holdings.

In general, direct stakers are fairly insensitive to yield fluctuations. They purchase ETH for price exposure and stake it as a secondary benefit, provided the price upside remains attractive.

Overall, sources of staked ETH are inelastic. Most users continue to stake unless there is a significant price spike, which is more common in less established networks like NEAR. In such cases of high volatility, users may prefer to realize their profits before deciding whether to continue staking.

Profitability

The SSP operators we spoke to don’t expect the profitability change for them to be dramatic. However, we note that they were at the larger side of the spectrum. That means their fixed costs were lower as percentage of their current revenue. Subscale operators might find themselves unable to leverage these fixed costs.

We expect this will manifest in cutting costs. Our operators mentioned that reducing headcount, specifically in the engineers managing staking set-up, is the most likely first line of defense against falling revenues.

Operators further mentioned that the cost take-out could continue on the infrastructure side, though we view that opportunity set to be limited, as SSPs already run fairly efficient infrastructures. Here we again note the pernicious effect on small operators: smaller SSPs have less space to cut on the infrastructure side. Though there is some wiggle room, our conversations have revealed that cutting infrastructure costs more would cut into the necessary costs that would significantly hamper the quality of their service. On the other hand, larger SSPs generally said that they could reduce “nice-to-have” infrastructure costs.

The last cost-reduction avenue are administrative expenses, however those are marginal and unlikely to move the needle.

Hence, we expect the profitability of small operators to suffer disproportionately more.

ETH Inflows

Lido

The Lido portion depends on the growth of (i) ETH staked on Lido and (ii) the allocation towards SSPs. Lido’s base is retail heavy and doesn’t look at yield as the primary variable when staking. Hence, we expect the number of ETH staked on Lido to be relatively stable. However, if it decreases on the margin, it’s possible that Lido would consider changing the allocations to transfer the impact onto SSPs. Thus, we are cautious about the growth in Lido inflows.

Institutions

We think that institutions will have an incrementally lower appetite for staking. The decrease in yield will slim down the margin between staking and their opportunity cost. Nevertheless, institutions are yield starved today and we don’t expect large-scale scaling down of staking.

Overall, SSPs inflows should suffer, though even the effect on them won’t be catastrophic. Nevertheless, an increasing centralization among SSPs appears imminent. These platforms compete on added services, particularly those most valuable to institutions. However, these services introduce a layer of fixed costs that create challenges for smaller providers. When staking yields decrease, smaller direct service providers may struggle to maintain these services.

As a result, any decrease in the inflows of ETH will be felt by the smaller SSPs, further reducing their ability to remain competitive against larger SSPs with a greater resource base. We think this will lead to a concerning level of industry centralization.

Lido’s strategy of diversifying its operator base serves as a potential countermeasure to centralization. Per its most recent Q3’24 report, Lido added 130 new node operators, bringing its total on DVT platform to 236 unique operators, slowing the consolidation trend by preventing larger players from disproportionately dominating the staking landscape.

Staking Pools

A staking pool lets people combine their cryptocurrency to collectively validate blockchain transactions and earn rewards, making it possible for smaller holders to participate in Proof-of-Stake networks when they couldn’t meet minimum requirements alone. In this paper, we are referring to actors such as Lido, which distributes stake uniformly across thirty-eight node operators.

Lido’s main module distributes stake uniformly among 38 node operators, and include additional modules include Simple Distributed Validator Technology (DVT) and Community Staking Model (CSM) [9].

The Simple DVT module tests distributed validator technology on Ethereum mainnet via Obol and SSV Network, enabling new stakers to join as node operators while improving security and decentralization through enhanced resilience.

The Community Staking Module enables anyone to become a Lido node operator with just an ETH deposit, offering smoothed rewards and a user-friendly experience to make staking more accessible than traditional solo staking while increasing protocol decentralization.

Size and Sources of Staked ETH

Lido is the largest staking pool, commanding 28% of all ETH staked. Lido’s staked ETH comes from sophisticated on-chain individuals and crypto native institutions. The average staker puts in around $80,000 worth of ETH.

Cost Structure

Per our conversations with Lido, the cost structure is mostly fixed. The main cost items are servers and engineers. We think that the cost distribution is similar to SSPs, where the bulk of the costs are eaten up by the people working on the infrastructure. The fixed cost curve is flat, but rises in a stepwise fashion for infrastructure expansion – e.g. a move from 100 to 150 ETH staked has minimal effect on costs, but going from 100 ETH to 200 ETH necessitates a large infrastructure investment.

Innovation Roadmap

Lido plans to integrate the Distributed Validator Technology (DVT). DVT should decentralize Lido’s validator set. By distributing validator responsibilities across multiple operators, Lido is reducing the risk of any single point of failure. That should ensure a more resilient and secure staking infrastructure. Implementation will begin in 2024. The roll out is expected to be gradual, as they test and refine the system.

Lido is also planning to introduce staking on new networks, expanding beyond Ethereum. This diversification gives users access to broader yield opportunities while spreading risk across multiple blockchain ecosystems. It allows Lido to position itself as a multi-chain staking solution, attracting a wider base of users. The timeline for adding these networks is flexible, but Lido aims to launch initial expansions throughout 2024 and 2025.

In parallel, Lido will enhance node operator participation with permissionless validation, opening up validator operations to more participants. This promotes decentralization by making it easier for smaller or independent operators to join and secure the network. The added diversity of node operators strengthens the overall network and reduces centralization risks. Lido plans to fully deploy this feature by mid-2024. The innovation is now live on testnests.

Inherently decentralizing

- Lido and other pools distribute ETH across various staking providers

- SSPs for example partner w/ Lido and wait for allocation

- Receive some part every time someone stakes with Lido

- Limits growth of operators by allocating new ETH staked disproportionately to smaller operators

- E.g. If there are 100 ETH staked on the platform, with 80 managed by Operator1 and 20 by Operator2, when new 10 ETH comes on the platform, both operators will receive 5 ETH (not actual figures)

Profitability

We think that Lido would be less affected by the proposal than solo stakers and SSPs. Lido’s staking base skews retail heavy compared to SSPs. The retail customers that we spoke to don’t consider yield to be their primary variable in staking with Lido. They regard Lido as better than the opportunity cost: letting their ETH lay unproductive. As long as that holds, Lido should maintain the vast majority of its staked ETH [6].

Nevertheless, Lido’s fees would compress, similarly to Coinbase, proportionately to the decline in yield on ETH.

ETH Inflows

Lido’s inflows are fairly hard to forecast, However, we believe that Lido should expand its market share in the upcoming years, being an incremental share taker thanks to its customer base. The customer base skews towards retail and is less price elastic than larger institutions.

We do note though that Lido should lose more of the staked ETH than Coinbase should the proposal pass. That’s because Lido’s staking base is larger (~$80k ETH staked on average) and is more acquainted with on-chain alternatives, compared to Coinbase’s retail-heavy stakers.

Innovation Roadmap

Lido’s innovation roadmap would likely not be that affected. Lido has one of the largest corporate treasuries in DeFi. Its leadership has proven that it is forward thinking and emphasizes innovation. One thing emphasized by Lido representatives when we spoke to them is that they realize the only way to survive in staking is to offer the best product. They understand that cutting innovation amidst the decrease in profits sets them up to be uncompetitive with other offerings in the future [9]. Thus, bare a dramatic decrease in profitability, we think that Lido should be able to maintain its innovation roadmap.

Centralized Actors

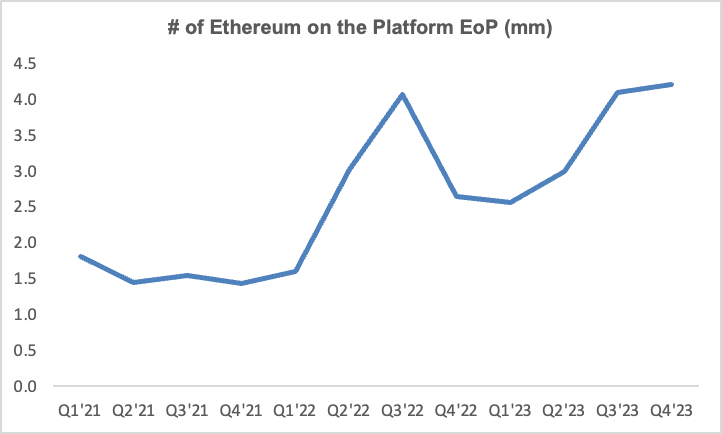

Coinbase currently has around 4.3 million ETH staked, valued at approximately $16 billion, with control over 20,000 validators. The majority of Coinbase’s staked ETH comes from retail customers, who tend to buy and hold crypto, viewing staking as a simple way to earn additional returns. Institutional staking, although a smaller share today, is expected to grow significantly due to larger capital allocations.

Looking ahead, Coinbase expects growth in both retail and institutional staking, with institutions likely to play a larger role due to their greater financial resources. Coinbase’s staking cost structure involves taking a 25% cut from staking rewards (reportedly lower for institutions, though Investor Relations didn’t disclose the number to us), which mainly covers fixed costs. This fee is justified by the platform’s strong brand and reliability, allowing users to earn staking rewards they otherwise wouldn’t participate in, given the onboarding barrier for on-chain staking solutions.

Impact of the Change

Despite the potential impact of these changes, staking flows into Coinbase are expected to remain steady and largely inelastic. Customers prioritizing security, compliance, and ease of use are likely to continue choosing Coinbase, with staking returns being a secondary concern. However, the increasing percentage of ETH on Coinbase raises concerns about the potential for a 51% attack. While Coinbase’s Investor Relations (IR) team claims they will work to avoid this risk, there is skepticism about their commitment given the company’s fiduciary duty to shareholders. IR mentioned that Coinbase could mitigate this risk by staking through third-party validators via Coinbase Cloud [5].

Number of ETH on Coinbase’s platform at the end of each quarter

Percentage of ETH on Coinbase’s platform staked

Distributed Validator Technology (DVT)

Distributed Validator Technology (DVT) represents a significant advancement in blockchain validator infrastructure decentralization. Unlike traditional setups where a single entity operates nodes, DVT enables validators to be run by a distributed network of nodes. This approach changes how rewards are distributed and infrastructure is managed. Companies like Lido are integrating with DVT to reduce reliance on single entities, aiming for a network of 14 operators collaborating to run validators [9].

DVT introduces challenges in reward distribution. Traditional staking pools typically charge 10% of rewards, but with DVT, this share must be divided among multiple operators. This fragmentation raises questions about DVT operation viability and optimal reward structures to ensure profitability for all participants.

Obol is a key player in this landscape, providing DVT solutions that enhance validator key security and management. Their approach is particularly crucial for liquid staking protocols, which view DVT as essential for achieving truly decentralized node operations [10]. While liquid staking protocols are early adopters, institutional adoption is still in exploratory phases.

DVT is increasingly seen as critical infrastructure for Ethereum’s consensus layer, essential for realizing blockchain decentralization. It enables validator participation from diverse geographic locations, enhancing network resilience and global representation.

Impact of the Change

The proposed reduction in Ethereum’s issuance rate poses significant challenges for the DVT ecosystem. This change disproportionately affects DVT operators who must split already reduced rewards among multiple entities. Current profitability estimates for DVT operations are concerning, with reports suggesting low returns for operator sets.

The impact extends beyond individual operators to the broader ecosystem. Liquid staking protocols may need to reassess the number of validators they can profitably support. There’s a risk that financial pressures could inadvertently favor larger, more centralized operators, potentially undermining DVT’s decentralization goals.

Geographic diversity in validator participation could also be at risk, as lower rewards might make it economically unfeasible for operators in developing regions to participate. This potential contraction in the validator pool affects both network security and cultural diversity.

To address these challenges, several strategies are being explored [10]:

- Reconsidering the traditional fee structure, potentially increasing operator fees.

- Developing more efficient infrastructure and implementing cost reduction strategies.

- Exploring alternative reward mechanisms or supplementary income streams for DVT operators.

While the issuance change presents significant challenges, it also catalyzes innovation and efficiency improvements. The coming months will be crucial in determining how the DVT model evolves to maintain decentralization while ensuring economic viability. The Ethereum community’s resilience suggests that creative solutions will emerge, potentially strengthening both DVT and the Ethereum network long-term.

7. Analysis of the Impact on the Space

Centralization

Under the new proposal, staking will become far less attractive than traditional finance (TradFi) yields, compounding the current challenges. That lowers the incentives for new entrants. Consequently, the consolidation trend is unlikely to reverse.

A possible countermeasure is incentivizing solo staking. Unfortunately, the solo staking community itself thinks that these measures will take 4-5 years to develop and implement. However, it is plausible that, by then, 70-80% of ETH may already be staked by large holders and venture capitalists. Implementing changes at that point will be difficult, as those benefiting most will resist.

For example, to reduce staking from 90% to 30%, drastic measures would be required to remove the 60% and will cause significant disruption.

The issuance reduction proposal, which would cut yields across the board to slow new staking, could make staking less appealing. Based on the proposal, at current rate of ETH invested, the real yield would fall from 2.5% to 1 % – a 60% reduction. This approach discourages incremental stakers from entering the market, but does nothing to counteract the underlying forces that lead to consolidation – cost and distribution advantages of large players that allow them to tap into price/yield-insensitive staker base.

8. Concluding Discussion

Our analysis of the current Ethereum staking model suggests that while the intentions behind the issuance curve are well-meaning, they might be addressing the wrong issues. The original issuance curve was somewhat arbitrary, a design the Ethereum Foundation adopted during the transition to Proof of Stake (PoS). As Ethereum’s issuance has become more modest and is approaching an equilibrium, profitability for staking has become increasingly challenging. The applications built on Ethereum make it risky to alter the issuance curve significantly. For example, Eigenlayer’s rapid growth can be attributed to the low profitability of staking, which has also led to greater centralization in staking activities.

Core Problem: Centralization in Staking

The primary issue lies in the fact that staking inherently drives centralization due to the PoS model and its economies of scale. Staking pools are currently the only mechanism countering this force, and they can rate limit the growth of individual operators. The measurable concentration of staking is a concern, especially when considering entities like Binance and Coinbase that do not disclose their on-chain activities. By decreasing the issuance yield, smaller players suffer more, while entities like Coinbase, which have less sensitivity to yield fluctuations and larger scales, can absorb lower profits. This scenario exacerbates the centralizing tendency.

Future Development Concerns

Ethereum is not yet prepared for the influx of institutional money that could fundamentally change its landscape. Currently, ETH remains small compared to other asset classes, but when institutions start allocating significant resources to ETH, entities like Coinbase and other centralized actors will be the primary beneficiaries. This poses a legitimate threat of a 51% attack, with Coinbase being poised to gain the most due to its compliance with regulatory standards.

Coinbase, as a public company focused on maximizing shareholder value, is unlikely to sacrifice revenue for the sake of decentralization. A concerning sign is that in Q3 2023, Coinbase stopped reporting the balance of ETH staked from institutional clients, which raises red flags about transparency. As of Q3 2024, Coinbase has also stopped reporting retail staked ETH. Without this information, the community has no visibility into the concentration of staking power. Staking pools, particularly Lido, have attempted to address these concerns in their core through distributing stake uniformly amongst node operators whitelisted by Lido DAO to limit the growth of individual operators.

The Role of Liquid Staking Tokens (LSTs)

The Ethereum community harbors concerns about LSTs because anything that exerts significant control over the network is viewed as a potential threat, leading to fears of cartelization and monopolistic practices (Ethereum Notes: Magnitude and Direction of Lido Attack Vectors). LSTs could potentially compete with ETH directly as a token, introducing use in transactions. However, while LSTs pose some risks, they also represent one of the most credible defenses against more significant threats, such as centralization by entities like Coinbase.

Lido has reached similar conclusions. The team doesn’t support changes in ETHs monetary policy, viewing these changes as unlikely to help counteract increasing consolidation. Instead, the protocol tries to leverage its market share to mitigate concerns through mechanism design. For example, by limiting the growth of node operators, Lido introduces checks that balance individual node operators market power.

Supporting Solo Stakers

Solo stakers are currently at a disadvantage in the staking landscape, with most new validators belonging to large liquid staking or restaking operations. There is a growing concern that solo stakers will not benefit from future proposals or be considered in the network’s evolution.

Staking exhibits strong returns to scale: as a platform gets larger, its returns on capital increase. Reducing returns to scale in staking is not a practical solution, as it could be easily gamed to appear as if more solo stakers are participating. Potential solutions include implementing offline correlation penalties and initial slashing penalties. These would penalize operators with correlated validator behavior, such as when multiple validators go offline simultaneously, which often indicates they are managed by the same operator. Although this is an imperfect solution, it encourages operators to diversify their setups, reducing the risk of correlated offline events and promoting a more decentralized network.