Last year, I became very interested in getting involved in the development of core Ethereum protocols. So I decided to participate in the Ethereum Core Developer Apprenticeship Program Cohort-one as a start.

I was specifically interested in EVM and Stateless Ethereum at the moment and finally worked on implementing a prototype predict-al of predicting access list for Portal Network clients.

Applying methodology like taint checking, the prototype, when tested with about one million historic transactions on Ethereum Mainnet, achieves an average improvement of 2.448x on reducing the number of iterations to retrieve state from the network.

Background

@pipermerriam initially proposed the idea of predicting access list in the Ethereum Core Developer Apprenticeship Program Cohort-one.

It’s crucial for blockchain decentralization that a regular user is able to run a node on resource constrained devices. The Portal Network is an in progress Ethereum research effort towards this goal. In the Portal Network, Ethereum state data including account balances and nonce values, contract code and storage values, should be evenly distributed across the nodes. A portal client that participates in the network typically exposes the standard JSON-RPC API,even though it only stores a small part of the whole state data of the network.

A portal client will encounter a new serious problem which does not exist in the current full nodes when it executes the API eth_call or eth_estimateGas, because it typically does not have necessary state data and has to retrieve them on demand from the network. If we keep the same implementation of EVM as the current popular execution layer clients in portal clients, the EVM engine will need to be paused to retrieve data from the network each time state data is accessed. This will dramatically slow down the EVM execution when the number of state to be accessed grows too large.

A potential solution for this problem is to build an engine that could predict a significant amount of the accounts and storage slots to be accessed before a transaction is actually performed. Then those predicted state data could be fetched concurrently instead of one by one. If this contract calls another contract’s methods, or the location of a storage slot to be accessed depends on another storage slot’s value, we couldn’t predict all state in one round. Once the predicted state data in last round have been retrieved, the tool should be run again with those values to find more states to be accessed until there’s no any more new states.

We could run one process to perform the actual EVM execution, and spawn another process at the same time to run this tool, predicting the transaction’s access list and retrieving their values from the network in the background. Another potential benefit of this solution is that the current popular implementation of EVM could be re-used by portal clients without much modification.

Prototype Implementation

When the tool receives a transaction payload, the sender and receiver can be easily extracted directly from the payload. Once these two accounts’ state data such as balances, nonces and bytecodes have been fetched from remote nodes, the next step is to find out more state accesses if the receiver is a contract or zero.

We can perform some simple static analysis with the retrieved contract bytecode to find out some state accesses with constant locations. For example:

PUSH1 0x00

SLOAD

But for some more complicated data structures, such as dynamic arrays and maps, the storage locations are usually dynamically computed with the provided parameters. For example:

// bytecode snippet of loading the value from a map by the provided key

//

// mapping(address => uint256) public balances;

// function balanceOf(address _owner) public view returns (uint balance){

// return balances[_owner];

// }

//

CALLDATALOAD

... // A lot of codes many jumpings are omitted here

JUMPDEST

PUSH 0

DUP1

PUSH 0

DUP4

PUSH FFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFF

AND

PUSH FFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFF

AND

DUP2

MSTORE

PUSH 20

ADD

SWAP1

DUP2

MSTORE

PUSH 20

ADD

PUSH 0

KECCAK256

SLOAD

Even though we can find out these access patterns by static analysis, obviously we still need a virtual machine to execute those bytecodes to compute the exact storage locations.

Taint Checking

A customized EVM has been implemented in this prototype to resolve the above issue. We can run a transaction with this EVM and record potential state accesses. Taint checking was introduced into this EVM to dynamically identify which state accesses should be recorded. At the same time, it also removed the need to pause the EVM executio when a state access happens.

Considering the following example described in YUL language, there are four possible different state accesses in this function.

function foo() -> result {

let x := 0

let y := 1

let m := sload(x)

let n := sload(y)

let z := 2

let k := gt(m, n)

switch k

case 0 {

result := sload(n)

}

default {

result := sload(z)

}

}

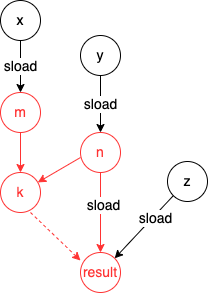

The graph below shows the flow of taint in the first round of running this tool. The returned value of any state access will be marked as tainted unless its value has already been retrieved from the network and saved into the local storage. Red nodes and arrows in this graph indicate taint, and dotted lines represent indirect influence.

Obviously m is tainted by sload in this round. The customized EVM only marks it as tainted and then continues to handle next opcodes. At the end of the execution of this function, there are four sloads to be found totally, but the location n of the third sload is a tainted value whose exact value is unknown at the moment. So only the other three untainted locations x, y and z will be recorded after this round.

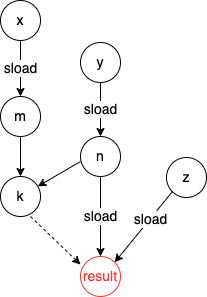

Once these three states have been retrieved, we can run this tool again. A new flow of taint is shown as the following.

In this second round, the variables m and n are not marked as tainted any more because their values have been retrieved and can be loaded from the local storage. Consequently, the switch condition k is also untainted.

If “case 0” will be executed by the EVM, only n will be recorded in this round. It will be merged with the other three state accesses found in the previous round as the final access list.

If “case 0” will not be executed, there’s no more new state access. Then the state access list found in the previous round will be the final access list.

Branch Traversal

Conditional branch is a very important case that needs to be handled carefully in this prototype. It’s very common in a contract that there are many conditional branches based on the values of other storage slots. We need to traverse both branches and look up the possible state accesses either way if the slot value has not been retrieved from the network yet.

The YUL code in the above section also shows an example of this case. The switch condition k depends on the values of storage slots x and y. We need to follow both branches when k is tainted. Obviously both branches would be traversed in the first round, but only one of them would be followed in the second round in this example.

In order to follow both branches, EVM context need to be backed up before the first branch is executed and restored before the second branch is executed. Branch paths will grow exponentially once there are nested branches with tainted conditions. So the depth of nested branches must be limited to avoid path explosion. If a conditional branch with a tainted value were repeatedly hit in the execution, it’s possible that there’s an infinite loop here. We also need to set a threshold to break it up.

Testing with Real Transactions

To test the prototype with real transactions on Mainnet, this tool needs to fetche data from an archived Geth node via the JSON-RPC API to simulate retrieving state data from other nodes in the Portal Network.

At first I ran the prototype predict-al with some historic blocks on mainnet to get predicted access lists. Then the trace-helper tool was ran with the same blocks to generate exact access lists for the validation of those predicted results. At last, another tool predict-analyze was executed to validate the outputs of predict-al and trace-helper and import them into a PostgreSQL database for further investigation.

The testing was performed with 5000 historic blocks on Ethereum mainnet from block 13580500 to 13585500 (exclusive). The total number of transactions is 1043603. The 671567 contract call or creation transactions among them are what we are interested in. The remained other simple Ether transfer transactions will be ignored in the analysis because they don’t interact with any contracts. Finally we got the following findings with these data.

Effectiveness of State Retrieval

To measure the effectiveness of state retrieval of this prototype, we define a factor as following:

factor = iterations-of-worst-case / (rounds-of-prediction + (total-pieces-of-state - number-of-correctly-predicted-accesses))

Suppose that there’s a historic transaction that involves touching 20 different pieces of state. The worst case is that the tool has to fetch them one piece at a time sequentially. That means 20 iterations of network lookups for this transaction.

Suppose the tool has predicted 18 possible state accesses in 4 rounds, we find out that only 15 of them are exactly accessed in this historic transaction after comparing them with the exact access list produced by the trace-helper tool. The remained 5 pieces of state that haven’t been predicted will still have to be fetched sequentially.

factor = 20 / (4 + (20 - 15))

According to the above expression, the factor of effectiveness should be 2.22. It means that this tool could fetch 2.22 pieces of state concurrently in each lookup on average, reducing the total iterations of lookups from 20 to 9.

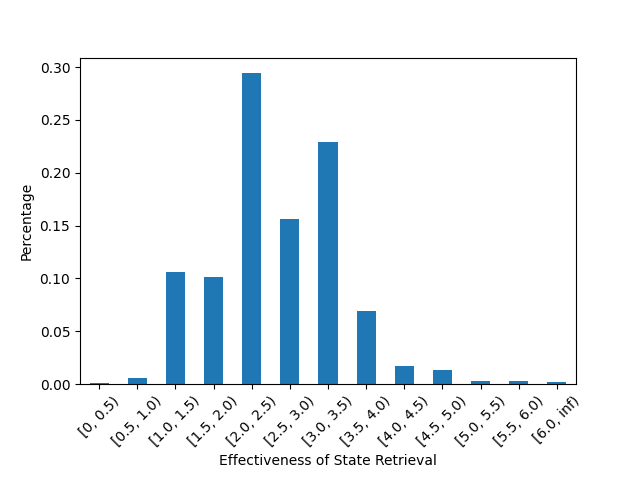

The tool achieved an average effectiveness factor of 2.448x in this testing. To better understand the average factor, we further show the effectiveness distribution across all 671567 contract call or creation transactions in the above figure:

- Most of them are showing an effectiveness between 1.0x and 4.0x

- Only 0.62% of them are less than 1.0x.

- With further investigation on these transactions, we found 80.4% of them are failed historic transactions. They reverted during the execution and only accessed small parts of the possible access lists that were predicted by the tool. This should explain why the tool got less effectiveness on most of them.

Prediction Correctness

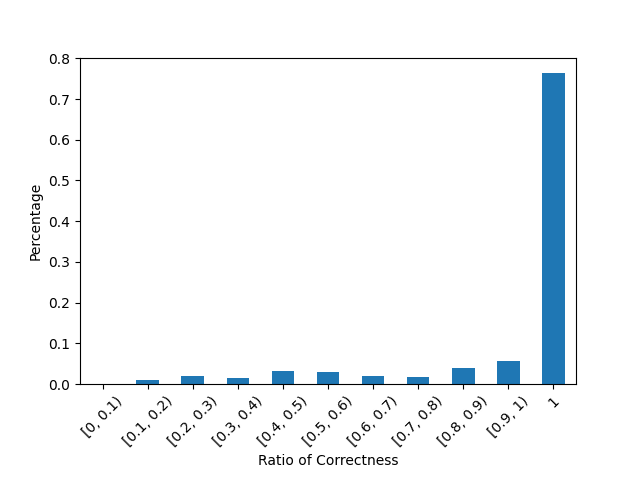

As mentioned in above section, all the predicted access lists need to be validated with the exact access lists produced by tracing the same transactions. The tool predict-al predicts the access list based on the state of the previous block, while the trace-helper generates the data based on both the state of the previous block and the position of this transaction in this block. This will usually cause some small difference between the datasets produced by these two tools. The ratio of correctness means how much percentage of the exact access list has been predicted correctly.

ratio = 15 / 20

For the example transaction mentioned in above section, the ratio should be 75%, according to the above expression.

The tool achieves an average ratio of 91.45% correctness. It means that on average, 91.5% of the exact state accesses have been predicted correctly in this testing. The figure above shows the distribution of the ratio of correctness. It reports that about 76.37% of them have been predicted with 100% correctness.

Frequently Accessed State

In the testing, we observed that some contracts and their methods are called far more frequently than others. The table below shows the top 10 contract methods that have been called with high frequency.

| Rank | Contract | Method | Count | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0xc02aaa39b223fe8d0a0e5c4f27ead9083c756cc2 | 0xa9059cbb | 120025 | 5.35% |

| 2 | 0xc02aaa39b223fe8d0a0e5c4f27ead9083c756cc2 | 0x70a08231 | 117522 | 5.23% |

| 3 | 0xdac17f958d2ee523a2206206994597c13d831ec7 | 0xa9059cbb | 105986 | 4.72% |

| 4 | 0xc02aaa39b223fe8d0a0e5c4f27ead9083c756cc2 | 0xd0e30db0 | 61787 | 2.75% |

| 5 | 0xa0b86991c6218b36c1d19d4a2e9eb0ce3606eb48 | 0xa9059cbb | 45667 | 2.03% |

| 6 | 0xc02aaa39b223fe8d0a0e5c4f27ead9083c756cc2 | 0x2e1a7d4d | 43122 | 1.92% |

| 7 | 0xc18360217d8f7ab5e7c516566761ea12ce7f9d72 | 0x76122903 | 33253 | 1.48% |

| 8 | 0xe592427a0aece92de3edee1f18e0157c05861564 | 0xfa461e33 | 32037 | 1.43% |

| 9 | 0x7a250d5630b4cf539739df2c5dacb4c659f2488d | 0x7ff36ab5 | 24397 | 1.09% |

| 10 | 0xe592427a0aece92de3edee1f18e0157c05861564 | 0x414bf389 | 23785 | 1.06% |

There are total 89647 unique contract methods that have been called 2245330 times in all of the 671567 transactions. The top 10 contract methods have been called 607581 times in total, and occupy 27.06% of all method calls.

It’s potential to improve the efficiency of this tool based on this kind of access pattern. For example, we could save bytecodes of some most frequently accessed contracts in local storage as a cache, then we could save one round to fetch those contracts’ bytecodes sometimes.

Conclusion

With the approach of taint checking, the prototype of this solution can predict about 91.45% of the access lists correctly and achieves an average 2.448x effectiveness of state retrieval. We also observed that some contract methods are called more frequently than others. This kind of access pattern could be utilized to improve this prototype.

It’s very important to reduce the time spent on state data retrieval when a portal client executes the API eth_call or eth_estimateGas. Predicting access list is a potential solution to resolve this problem, and as a result, speed up the EVM execution for portal clients.

Appendix

- Repository of predict-al

- Repository of trace-helper

- Repository of predict-analyze

- Predicted result of 5000 blocks by predict-al (238M)

- Tracer result of 5000 blocks by trace-helper (270M)

Reference

- Official Go implementation of the Ethereum protocol: go-ethereum

- Portal Network Specification

- EVM opcodes

- Understand EVM bytecode: 1 2 3 4

- Automated Detection of Dynamic State Access in Solidity

- The Winding Road to Functional Light Clients: 1 2 3

- An updated roadmap for Stateless Ethereum

- The 1.x Files: The State of Stateless Ethereum

- State Expiry & Statelessness in Review