Thanks for Ellie, Luca, Florian, and Ladislaus for all the feedback as well as the various teams who reviewed. Feedback is not necessarily an endorsement.

SCOPE is a minimal protocol for push-based synchronous composability, enabling contracts on Ethereum and rollups to call each other and immediately process results as if they lived on a single chain. It supports all directions, L1↔L2 and L2↔L2, within a single atomic execution scope. A minimal proof of concept can be found here.

Motivation

Ethereum’s rollup-centric roadmap offers a path to scale while preserving security, but it comes at the cost of fragmentation. Each rollup operates as an isolated execution environment with its own state, users, and developer ecosystem. This fragmentation weakens a core property that made Ethereum powerful in the first place: composability.

Composability allows smart contracts to interact like Lego blocks: permissionless, expressive, and instantaneous. As we scale horizontally across rollups, we must strive to heal this fragmentation. The ideal is synchronous composability (SC), where a smart contract on one chain can directly call a contract on another chain and immediately consume the result, preserving the developer experience of a single shared blockspace.

There are growing efforts around cross-chain intents; however, these approaches tend to narrowly focus on token transfers. Composability is a broader goal: it enables contracts to coordinate logic across chains, not just liquidity. Fabric has focused on shepherding the development of based rollups because they uniquely enable synchronous composability not just between rollups, but more importantly between Ethereum and rollups. Building on this foundation, SCOPE (Synchronous Composability Protocol for Ethereum) is a framework designed to realize the full vision of synchronous composability, ultimately strengthening Ethereum’s network effects.

Background

Synchronous composability is the property that allows a contract on one chain to invoke a function on another chain and immediately receive and act upon the result within the same execution context (e.g., a single L1 slot). Crucially, cross-chain interactions must be atomic: either both sides succeed or neither does.

Two notable designs have demonstrated atomic synchronous composability:

- CIRC (Coordinated Inter-Rollup Communication) introduced a mailbox-based framework for efficient, verifiable messaging between rollups. CIRC is a pull-based design: contracts on one chain can inspect messages sent from another chain and condition their execution on those messages. However, CIRC does not allow messages to trigger execution, it requires two transactions: one to write a message on the source chain, and another to consume it on the destination chain.

- Ultra Transactions adopt a push-based model, packaging all cross-chain activity into a single L1 bundled transaction containing blobs and settlement proofs. If an

XCALLOPTIONSprecompile is introduced, contracts can seamlessly call contracts on other chains. Any L1 contract can defer its execution to a cheaper rollup execution environment if they integrate with anExtensionOraclecontract and are willing to trust the Ultra transaction’s proof system.

SCOPE

What is it?

SCOPE builds on both prior approaches to offer a general-purpose framework for synchronous, trust-minimized cross-chain function calls:

- From CIRC, it inherits efficient, verifiable message accounting using mailbox commitments.

- From Ultra Transactions, it adopts a push-based execution model and leverages account abstraction bundlers to unify cross-chain execution into a single atomic scope.

SCOPE provides both:

- A set of standardized smart contracts (e.g.,

ScopedCallable) that rollups can inherit to support SC calls. - A derivation-friendly protocol that rollups can implement to ensure compatibility during cross-chain execution, bundling, and verification.

ELI5

Imagine Ethereum as the mainland and each rollup as an island just offshore. Today, communicating between islands is like sending a message in a bottle. It drifts for minutes or hours before arriving, and the sender gets no acknowledgement, let alone a usable response. SCOPE makes it feel like all the islands are connected to the mainland, where full conversations can happen instantly in both directions. You can speak, get an answer, and act on it right away, restoring the seamless coordination that Ethereum once had before the islands formed.

SCOPE enables rollups to not only send messages between each other and L1 atomically, but also lets users on one chain call functions on other chains and immediately receive and process the result. This gives the experience of operating on a single chain while retaining the scalability benefits of rollups.

How does it work?

At its core, SCOPE formalizes the accounting model required for verifiable push-based cross-chain transactions. Each participating chain maintains four rolling hashes and a single bytes mapping that represent the collective sequence of cross-chain requests and responses:

requestsOutHash: records outgoing cross-chain calls initiated by this chain.requestsInHash: records incoming cross-chain calls to be executed on this chain.responsesOutHash: records outgoing responses from cross-chain calls executed on this chain.responsesInHash: records incoming responses from cross-chain calls initiated by this chain.responsesIn: records incoming responses from cross-chain calls initiated by this chain as raw bytes.

The scopedCallable interface defines how these values are updated:

interface IScopedCallable {

/// @notice Struct describing a cross-chain function call.

struct ScopedRequest {

address to;

uint256 value;

uint256 gasLimit;

bytes data;

}

/// @notice Initiates a synchronous cross-chain call.

/// @dev Emits an event, updates a nonce, and updates the requestsOutHash.

/// Reads the result from the responsesIn array (pre-filled by the sequencer).

/// @param targetChainId The ID of the chain the `ScopedRequest` will execute on.

/// @param from The address that initiated the cross-chain call on the source chain.

/// @param request Encoded function call for the destination chain.

/// @return response The result bytes returned from the responsesIn array.

function scopedCall(

uint256 targetChainId,

address from,

ScopedRequest calldata request

) external payable returns (bytes memory response);

/// @notice Executes a cross-chain call.

/// @dev Called by the sequencer. Updates requestsInHash, emits an event, and updates responsesOutHash.

/// @param sourceChainId The ID of the chain the `ScopedRequest` was initiated from.

/// @param from The sender address on the origin chain.

/// @param nonce A unique nonce for deduplication.

/// @param request Encoded call to execute locally.

function handleScopedCall(

uint256 sourceChainId,

address from,

uint256 nonce,

ScopedRequest calldata request

) external;

/// @notice Pre-fills the responsesIn array with pre-simulated responses of cross-chain calls.

/// @dev Each response updates the responsesInHash for the corresponding chain ID.

/// @dev All arrays must have the same length (i.e., chainIds[i] corresponds to reqHashes[i]).

/// @param chainIds The chain IDs from which the responses originate.

/// @param reqHashes The hashes of the original cross-chain requests.

/// @param responses The execution results from the destination chain.

function fillResponsesIn(

uint256[] calldata chainIds,

bytes32[] calldata reqHashes,

bytes[] calldata responses

) external;

/// @notice Returns the current rolling mailbox hashes for a given chain.

/// @param chainId The remote chain ID whose rolling hashes are tracked.

/// @return requestsOut Rolling hash of this chain's outbound requests.

/// @return requestsIn Rolling hash of this chain's inbound requests.

/// @return responsesOut Rolling hash of this chain's outbound responses.

/// @return responsesIn Rolling hash of this chain's inbound responses.

function getRollingHashes(uint256 chainId)

external

view

returns (

bytes32 requestsOut,

bytes32 requestsIn,

bytes32 responsesOut,

bytes32 responsesIn

);

}

The central primitive exposed to developers is the scopedCall() function. This function allows a contract on one rollup to synchronously invoke a function on another rollup and immediately consume the result. When scopedCall() is invoked, it appends a unique request identifier to the source chain’s requestsOutHash and reads a pre-filled response from the local responsesIn mapping. From the caller’s perspective, this interaction appears synchronous because the sequencer has already simulated the call on the destination chain and populated responsesIn in advance. The name *scopedCall* reflects the fact that the entire cross-chain interaction (request, execution, and response) is resolved within a single atomic execution scope, giving the illusion of local composability across chains.

On the destination chain, the sequencer executes handleScopedCall(), which mixes in the same request identifier to its requestsInHash, executes the ScopedRequest, and updates the responsesOutHash with the result. This output is then relayed back and inserted into the source chain’s responsesIn.

At settlement time, the bridge verifies that both chains respected the correct ordering of requests and responses. Specifically, it checks that:

- the source chain’s

requestsOutHashmatches the destination chain’srequestsInHash - the source chain’s

responsesInHashmatches the destination chain’sresponsesOutHash

If any call was skipped, reordered, or tampered with these rolling hashes would not match and the rollups would fail to settle, ensuring atomicity.

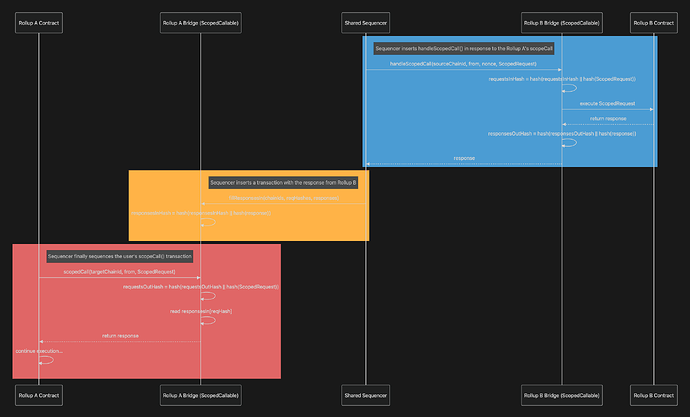

L2↔L2 Synchronous Composability

SCOPE works especially cleanly for L2↔L2 interactions. Suppose a contract on Rollup A needs to call a function on Rollup B. The shared sequencer observes A’s scopedCall() and immediately injects a matching handleScopedCall() on B. After executing the target function on B and obtaining the response, the sequencer pre-fills a fillResponsesIn() transaction on A so that, by the time A’s scopedCall() actually runs, it can read and act on the response synchronously, exactly like a local call.

Starting from initial hashes of

H(0), the flow yields: B.requestsInHash = A.requestsOutHash = H(H(0) || H(ScopedRequest)) and A.responsesInHash = B.responsesOutHash = H(H(0) || H(response)). If the sequencer incorrectly injects the request, B’s requestsInHash won’t match A’s requestsOutHash (derived from scopedCall()). If the sequencer incorrectly relays the response, A’s responsesInHash won’t match B’s responsesOutHash (derived from handleScopedCall()). Either mismatch breaks the equality checks at settlement and is equivalent to tampering with EVM execution, which standard state transition proofs will reject.

Advantages

- Parallel proving: Each rollup independently proves its own state transition in parallel, since both chains have the full ordered sequence of transactions. The only cross-chain dependency is the final rolling hash equivalence check at settlement.

- No mandatory shared sequencer: While a shared sequencer can optimize latency, SCOPE works with independently sequenced rollups as long as they share a settlement layer and trust each other’s sequencing. This makes it directly compatible with ecosystems like the Optimism Superchain.

- No real-time proving requirement: Unlike synchronous L1↔L2, L2↔L2 calls don’t require validity proofs to be generated in the same slot. The only requirement is that the participating rollups eventually settle together so that rolling hash equivalence can be verified.

- Amortized costs through shared commitments: When two rollups commit to a shared L2↔L2 execution, they 1) can share blob space and 2) share a single validity proof. This reduces per-rollup overhead and allows smaller rollups to amortize blob and proof costs across multiple participants.

L1↔L2 Synchronous Composability

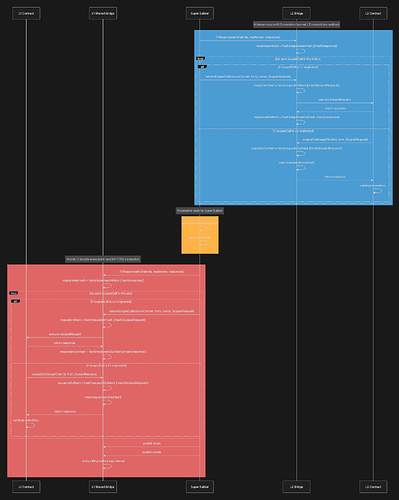

L2↔L2 synchronous calls are relatively straightforward to reason about assuming shared sequencing and shared settlement, but introducing L1 into the mix complicates things. To make synchronous L1↔L2 scopedCall() viable, we need to address three intertwined challenges: control over L1 blockspace, atomicity between chains, and the ability to execute L1 transactions on behalf of users.

At the center of SCOPE is a super builder, inspired by the Ultra Transactions model. The super builder is responsible for simulating the entire cross-chain call (both the L1 and L2 legs) and ensuring everything settles atomically within one L1 slot. This requires tight coordination with the L1 proposer and the L2 sequencer, or ideally, for the super builder to act as both.

L1 blockspace control: The first challenge is that only the L1 proposer decides what gets included in a block. If the L2 sequencer simulates a scopedCall() assuming an L1 state, but the L1 proposer invalidates that state by inserting or reordering transactions, the L2’s simulation is invalid and settlement will fail. To avoid this, the super builder must have determinism over the L1 contents at the time of L2 proof generation. This implies the super builder either is the L1 proposer or coordinates sequencing with them.

Real-time settlement: Next, atomicity requires both chains to settle together and roll back if the rolling hash checks fail. But with L1↔L2, only the rollup state can roll back. To preserve atomicity, all scopedCall() activity (L1 function calls, blob submissions, and proof verifications) must be bundled into a single L1 transaction. If any rolling hash check fails, the entire bundle reverts, rolling back the L1 and rollup states. Importantly, because the L2 must consume L1 state, it must simulate and settle within the same L1 slot, introducing a real-time proving requirement not present in the L2↔L2 case.

Delegated Execution: Finally, rollups often allow their sequencers to inject transactions on behalf of users, e.g., minting ETH after a deposit. The L1 doesn’t natively support this delegation, so to support L2→L1 scopedCall(), we rely on EIP-7702 delegated execution. Users sign a payload authorizing an action, and the bundler wraps that payload into an L1 transaction.

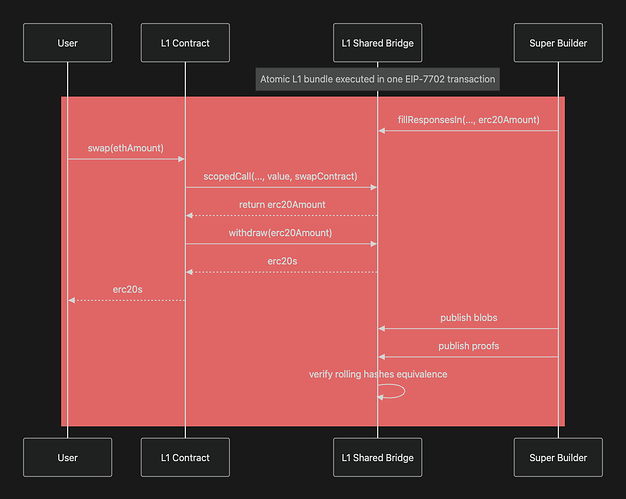

Example

This example shows a cross-chain token swap using scopedCall() where the L1 contract interacts with an L2 to execute the swap and immediately withdraw the resulting ERC-20s back on L1. The sequencer pre-fills the swap result via fillResponsesIn(), allowing the withdrawal to happen in the same transaction prior to the rollup settling. Unlike standard Merkle proof–based withdrawals, the withdraw() call here can be permissionless because the entire bundle, including the withdrawal, is protected by atomic rollback if the proof fails or the rolling hashes mismatch, preventing any unauthorized draining of funds.

Simulation

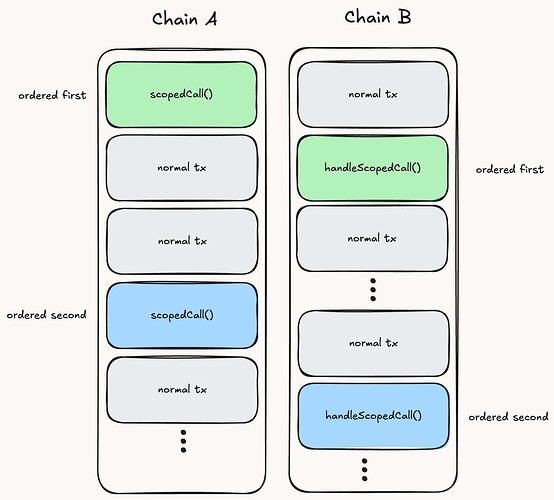

When simulating and sequencing, the super builder must ensure that each rollup respects a partial order over cross‑chain calls:

- On the source chain, all

scopedCallsmust appear in a well‑defined relative order. - On the destination chain, all corresponding

handleScopedCallsmust appear in the matching relative order. - Everything else (ordinary transactions) may be interleaved as long as they don’t mutate the

ScopedRequestpayload or the computedresponsein ways that would change the rolling hashes.

Concretely:

- After sequencing a

scopedCall(req), the super builder must not include source‑chain transactions that changereq, e.g., mutateto,value,gasLimit, ordata. - After simulating

handleScopedCall(req)and capturingresponse, the super builder must not include destination‑chain transactions that would changeresponse.

To simulate, the super builder would:

- Intercept the source chain’s

scopedCall() - Locally update the source chain’s

requestsOutHash - Insert and execute the

handleScopedCall()into the destination chain - Pass the

responseback to the source chain’s execution

By repeating this process, the super builder will determine all response values necessary to call fillResponsesIn().

Appendix

Here we analyze popular rollup stacks to identify what changes are needed to support SCOPE assuming the target is synchronous L1↔L2 composability.

Core SCOPE requirements (L1↔L2)

- Shared Sequencer: A common sequencer must coordinate the cross-chain transaction flow across all participating rollups.

- L1 Client Modifications: L1→L2

scopedCall()require different behavior during simulation than execution. - L2 client modifications: Beyond the core state transition function, rollups must prove rolling hash equivalence for all cross-chain requests and responses, ensuring verifiable consistency between participating chains.

- L1 Bridge Modifications: The bridge must track rolling hashes (

requestsInHash,requestsOutHash,responsesInHash,responsesOutHash) to enforce atomicity via equivalence checks during settlement. - Real-Time Proving: Rollups must generate and submit validity proofs (i.e., a non-contestable rollup) within the same L1 slot to participate in atomic

scopedCall()execution. - L1 Proposer Coordination: Either the sequencer must be the L1 proposer, or it must obtain a state lock to guarantee the L1 leg of

scopedCall()executes exactly as simulated. - Return Value Support: Simulate cross-chain calls ahead-of-time and track

responsesOutHash,responsesInHash, and theresultsInmapping on both L1 and L2. This allows calling contracts to synchronously consume return values as if the call were local.

Case Study: Ethrex

The Ethrex stack supports push-based L1→L2 cross-chain calls without return values via privileged transactions, and pull-based L2→L1 message passing.

L1→L2 Today

-

Calling

CommonBridge.sendToL2()sends an arbitrarySendValuespayload, which encodes the target L2 function call. The payload’s hash is appended to thependingTxHashesarray, and aPrivilegedTxSentevent is emitted. -

The sequencer listens for the PrivilegedTxSent event and injects a

PrivilegedL2Transactioninto the L2 mempool. This transaction executes the function call encoded inSendValues. -

During settlement, the proving system collects all

PrivilegedL2Transactions, computes their rolling hash, and verifies that it matches the rolling hash ofpendingTxHashesas computed on-chain viaOnChainProposer.verifyBatch().This mechanism is equivalent to verifying that L1

requestsOutHashmatches L2requestsInHashunder the SCOPE model.

L2→L1 Today

- Calling

L2ToL1Messenger.sendMessageToL1(bytes32 data)emits anL1Messageevent wheredatais the hash of the message being sent. - The sequencer constructs a Merkle tree from all such

datavalues and commits the root during L2 settlement. - To finalize the message, a user supplies the raw message and Merkle proof, allowing verification that the message was committed by the L2.

Currently, the L1 bridge only supports token withdrawals. General-purpose L1 function calls initiated by the CommonBridge contract are not yet supported but would be straightforward to add.

SCOPE compatibility requires:

- Replace

sendToL2()withscopedCall(), introducingresponsesOutHash,responsesInHash, and theresultsInmapping to allow calling contracts to immediately consume return values from cross-chain function calls. - Rather than waiting for

PrivilegedTxSentevents emitted on L1, the sequencer should pre-injectPrivilegedL2Transactionsbefore L1 block confirmation, enabling synchronous execution across chains. - Replace pull-based L2→L1 messaging with push-based

scopedCall()initiated from L2 and handled viahandleScopedCall()on L1. This enables arbitrary L1 contract calls to execute within the same L1 slot.

Case Study: OP Stack

The OP Stack supports bidirectional, push-based cross-chain calls without return values.

SCOPE can also be applied to the SuperChain to enable L2↔L2 synchronous composability without requiring a shared sequencer or real-time proving as long as the participating rollups share a settlement layer and mutually trust each other’s sequencing.

L1→L2 Today

- Calling L1

CrossDomainMessenger.sendMessage()allows arbitrary opaque bytes to be sent as calldata to a target L2 contract. - The

OptimismPortal.depositTransaction()escrows any ETH in a lockbox and emits aTransactionDepositedevent. - The sequencer listens for

TransactionDepositedevents and injects a transaction on L2 that callsCrossDomainMessenger.relayMessage(), which executes the L2 function call using the previously sent data.

The derivation pipeline ensures that all TransactionDeposited events correspond to a message being relayed. Otherwise, the sequencer has committed fraud.

L2→L1 Today

- Calling L2

CrossDomainMessenger.sendMessage()allows arbitrary opaque bytes to be sent as calldata to a target L1 contract. L2ToL1MessagePasser.initiateWithdrawal()records the message hash in asentMessagesmapping and emits aMessagePassedevent.- The sequencer proposes an L2

outputcontaining anoutput_rootcommitting to the state of thesentMessagesmapping. - The user proves message inclusion by calling L1

OptimismPortal.proveWithdrawalTransaction()with a merkle proof. - After the fraud proof window passes, calling L1

OptimismPortal.finalizeWithdrawalTransaction()executes the L1 function call.

If validity proofs were used, this pull-based approach could be reduced to two transactions: one to initiate the message on L2 and one to prove and finalize execution on L1.

SCOPE compatibility requires:

- Support validity proofs capable of real-time proving to allow the rollup to settle within a single L1 slot.

- Support synchronous L1→L2

scopedCall()by allowing theop-nodeto set [SequencerConfDepth](https://github.com/ethereum-optimism/optimism/blob/f70219a759e1da31e864c0ccdc2c757689aba3ec/op-node/rollup/driver/config.go#L12) = 0and enablingCrossDomainMessenger.relayMessage()to be called before theTransactionDepositedevent is emitted on L1. - Enable synchronous L2→L1 calls by replacing the current multi-step L2→L1 message passing process with a single L2-initiated

scopedCall().

Case Study: Taiko

The Taiko stack supports bidirectional, pull-based cross-chain calls without return values.

L1→L2

- Calling

Bridge.sendMessage()allows an arbitraryMessageto be sent, which encodes a function call to a target L2 contract. TheMessageis hashed (creating a signal) and stored in the L1SignalServicecontract. - The user generates a storage proof using the standard

eth_getProofRPC, proving that their signal exists on L1. - Each Taiko block begins with an anchor transaction that injects the current L1 world state root and a list of new signals. These signals are then written to the L2

SignalServicecontract. - By calling L2

Bridge.processMessage()with theMessageand L1 storage proof, the user proves the message was included on L1. This is done by verifying the signal against the L1 world state root and the L2SignalServicecontract. _invokeMessageCall()then executes the function call encoded in theMessageon the target L2 contract.- During settlement, the system verifies that the signals reported in the anchor transaction match what was written to the L1

SignalService.

The check for equivalent signals is functionally equivalent to comparing the L1 requestsOutHash and L2 requestsInHash in SCOPE.

L2→L1

- The user calls

L2 Bridge.sendMessage(), which stores the message hash (signal) in the L2SignalServicecontract. - Once the rollup settles and its world state is finalized, L1

Bridge.processMessage()can be called with the originalMessageand a storage proof showing the signal existed in the L2SignalServicecontract. _invokeMessageCall()then executes the encoded function call on the L1 contract.

SCOPE compatibility requires:

- Replace the current signal-based flow with a push-based model where

Bridge.sendMessage()becomes equivalent toscopedCall(). Instead of recording individual signals and relaying them to the destination chain, the sequencer relays the fullMessagedirectly. The source chain appends the message to a rollingrequestsOutHash, while the destination chain computes a matchingrequestsInHashduringhandleScopedCall(). This removes the need for Merkle proofs as any tamperedMessagecauses the rolling hash check to fail, preventing settlement. Bridge.processMessage()becomes equivalent tohandleScopedCall()and should be called immediately, executing theMessageand updating bothrequestsInHashandresponsesOutHash. This function can be permissionless, as a rational proposer must ensure messages are handled in the correct order for the rollup to settle (i.e., sorequestsInHashmatchesrequestsOutHash).

Case Study: Linea

The Linea stack supports bidirectional cross-chain calls without return values, using either push- or pull-based delivery depending on whether the Postman Service is used.

L1→L2 Today

- Calling

L1MessageService.sendMessage()sends opaque bytes (calldata) to a target L2 contract. The message hash is incorporated into a rolling hash and aMessageSentevent is emitted on L1. - A coordinator service monitors these events, waits two L1 epochs for finality, and then calls

L2MessageManager.anchorL1L2MessageHashes()on L2. This writes the message hashes to L2 and emits aRollingHashUpdatedevent, ensuring the same rolling hash can be recomputed on both chains. - Finally,

L2MessageServiceV1.claimMessage()executes the L2 function call, sets a flag to prevent replays, and emitsMessageClaimed. This can either be called manually by the user or automatically by the Postman Service if the user prepaid an L1 fee. - At settlement time, the final

RollingHashUpdatedemitted by L2 is checked against the rolling hash on L1 to verify message consistency across chains.

This mechanism is equivalent to verifying that L1 requestsOutHash matches L2 requestsInHash under the SCOPE model.

L2→L1 Today

- Calling

L2MessageServiceV1.sendMessage()emits aMessageSentevent containing the message hash and encodes arbitrary opaque bytes as calldata for a target L1 contract. - During settlement, the prover constructs a Merkle tree of all emitted message hash values and commits the Merkle root to L1.

- To complete the message, the user (or the Postman Service) calls

L1MessageService.claimMessageWithProof()with the raw message and its Merkle proof, which executes the L1 function call.

SCOPE compatibility requires:

- Remove the

anchorL1L2MessageHashes()step and instead update the L2 rolling hash incrementally duringclaimMessage(), which becomes equivalent tohandleScopedCall(). The sequencer must enforce that messages are claimed in the correct order to guarantee rolling hash consistency between L1 and L2. - Replace the current Merkle proof verification used in

claimMessageWithProof()with a push-based model usingscopedCall()initiated from L2. The L2 tracks arequestsOutHashand the L1 computes a matchingrequestsInHashwhenhandleScopedCall()is called. LineaRollup.submitBlobs()andLineaService.finalizeBlocks()must be bundled together and executed atomically. This ensures that the L2 settles in real time.

Based Preconfirmations and SCOPE

Preconfirmations are not a strict requirement for SCOPE. One could imagine a “total anarchy” based rollup where anyone can serve as the super builder, proposing valid bundles containing cross-chain calls, without offering preconfs. This model works, but naturally, preconfs can improve UX by giving users earlier certainty about their transaction outcomes.

Execution preconfs are typically considered the gold standard, but SCOPE’s order-of-operations complicates it: the post-state of a scopedCall() differs between simulation and execution due to the need to populate the responsesIn mapping. For efficiency, a super builder might insert a single fillResponsesIn() call after all simulations have run, rather than before each scopedCall(). This can be worked around on rollups by placing fillResponsesIn() immediately before every scopedCall(), which is gas-feasible. On L1, an alternative is for the super builder to preconfirm the pre- and post-rolling hashes along with their corresponding request and response data. This approach lets users reliably learn the results of cross-chain requests in a way that is easier to prove in the event of faults and easier to issue from the super builder (since it doesn’t require intermediate state roots).

Prior work such as CUSTARD explores extending the viability of “super transaction” preconfs made ahead of the super builder’s slot. More research is needed to determine whether such early scopedCall() issuance is safe when ScopedRequests depend on arbitrary stateful data that cannot be locked with the techniques CUSTARD describes (e.g., a ScopedRequest may contain pricefeed data determined at the time scopedCall() is executed, which is likely different from the slot it is simulated and preconfirmed in).

SCOPE vs AggLayer

SCOPE and AggLayer both aim to enable trustless cross-chain message passing, but they approach the problem from different angles. AggLayer is a fully fledged interoperability protocol with its own settlement rules, while SCOPE, despite the word “protocol” in its name, is primarily an accounting framework that can be overlaid on existing systems like AggLayer, the Superchain, or the Elastic Network.

Both systems share the same pessimistic proof philosophy: chains independently prove their own state transitions and only settle if cryptographic equivalence checks pass. In AggLayer, this manifests through the “Local Exit Tree,” whose root plays a similar role to SCOPE’s requestsOutHash. The difference is that AggLayer and similar protocols do not natively support synchronous return values from cross-chain calls. Messages go out, but nothing comes back in the same execution.

SCOPE extends this model by also tracking inbound responses, for example through a responsesInHash or a hypothetical “Local Entrance Tree.” This allows chains to synchronously consume return data as if they were part of one unified environment. The result is a shift from simple message delivery to a true shared execution scope, while preserving the same settlement-time safety guarantees.