Tracing bad funds through shielded pools

I want to explain an unhinged idea for tracing bad funds through a shielded pool, whilst keeping as much as possible private.

Logline

Dr Evil stole one-hundred billion dollars and fed it into a privacy protocol.

Somehow, the theft and the deposits went unnoticed for a while, and the deposit delay window has now passed. The money’s in the system. Private transfers ensue. No one knows good notes from bad notes. Times are bad.

Eventually, someone realises the theft and sounds the alarm.

How do users identify contaminated notes in their balance? How do we maximize privacy? How can we identify contaminated withdrawals (and should we)?

Headline aim: Enable a note owner to identify how much of their note is descended from “bad” deposits, without leaking anything else to anyone.

Super high-level

A user has a note. The note contains encrypted information that they cannot decrypt, about the deposits which contributed towards their note.

notes[i][j] = {

owner,

amount,

randomness,

deposits: [

{

<unintelligible ciphertext>,

<unintelligible ciphertext>,

},

{

<unintelligible ciphertext>,

<unintelligible ciphertext>,

},

{

<unintelligible ciphertext>,

<unintelligible ciphertext>,

},

{

<unintelligible ciphertext>,

<unintelligible ciphertext>,

},

...

],

}

Everything is nice and private.

If, some time later, a deposit is blacklisted, and if this note is a descendant of that “bad” deposit, then the user will suddenly learn this information:

notes[i][j] = {

owner,

amount,

randomness,

deposits: [

{

<unintelligible ciphertext>,

<unintelligible ciphertext>,

},

{

<unintelligible ciphertext>,

<unintelligible ciphertext>,

},

{

The bad deposit_id,

Some fraction to deduce how much of that 'bad' deposit

is contained within this note,

},

{

<unintelligible ciphertext>,

<unintelligible ciphertext>,

},

...

],

}

The user can then execute a dramatically-named “decontamination circuit” to create a new note which does not contain this bad deposit_id.

Caveats

No one’s read this yet.

I’m not really advocating for this approach, but it’s a fun design which attempts to solve a problem that I haven’t seen get solved before.

I can think of some strong criticisms, which are laced throughout this doc (and summarised at the end).

It might just serve as a reference for posterity.

Hopefully it’s an interesting read ![]()

Intro

If you want a really eloquent intro to this topic, read sections I and II of the Privacy Pools paper.

Here’s my tl;dr:

Some people would prefer privacy when transacting on a blockchain, so teams are exploring how to enable private blockchain transactions. A common pattern is as follows:

A user can deposit their tokens into a so-called “Shielded Token Pool”. Some time later, they can withdraw their tokens to another address. The aim of such protocols is to break the observable link between the deposit address and the withdrawal address.

Some protocols also enable private transfers of the tokens that have been deposited into the pool, whereby observers won’t be able to deduce who sent what to whom. It’s these deposit-transfer-withdraw protocols that I find most interesting.

A problem with all of these pools is that bad actors can also use them, and indeed there have been instances of bad actors sending ill-gotten funds into such pools. Once deposited, it becomes harder to trace the bad deposits, and it becomes harder to distinguish good withdrawals from bad withdrawals.

And so, various projects have sought to resolve this problem.

Approaches include:

- Identifying bad deposits before they can enter the pool, by introducing a deposit delay.

- Limiting the amount of money that can be deposited into the pool over some time period.

- Only allowing deposits from reputable actors.

- Enabling a user to provide proofs of disassociation from bad actors, or proofs of association with only good actors.

- Encrypting the details of every transaction to a 3rd party (such as a regulator or auditor or accountant), or sharing viewing keys with a 3rd party.

- Relaxing some privacy guarantees to enable some degree of traceability of all funds through the pool.

These approaches all have interesting trade-offs which we’ll touch on below.

The idea I’ve been toying with is as follows:

When a user is sent a note, it would contain a list of re-randomized encryptions of all upstream deposit_ids that contributed any value towards that note, along with encryptions of how much value each of those deposits contributed towards the note.

Under ideal circumstances, a user’s note wouldn’t be the descendant of any “bad” deposits, and in such cases they should have privacy comparable to zcash: the user wouldn’t be able to learn which deposits have contributed towards their note.

If a deposit is publicly deemed “bad”, however, then the design enables all downstream note owners to be able to learn how much of that bad deposit has flowed into their note. Crucially, no further information is leaked to a note owner beyond “X amount of my note is considered to have originated from this bad deposit_id”. Observers of the pool should not learn any information.

Ideally, a bad deposit would be identified and flagged as “bad” before it can enter the system, e.g. through some delay period. This way, it wouldn’t have the chance to “corrupt” honest users’ funds. But what if the delay isn’t long enough? Or what if due dilligence missed something? I thought it’d be interesting to explore how to identify bad funds that manage to slip through such a deposit-delay net, without leaking the transaction graph of users.

Edit after writing: Railgun actually experienced this problem recently: https://x.com/dethective/status/1994397800847589736?s=20

We’ll hit some scalability problems along the way, and explore how to mitigate those.

Background

Here’s a quick reminder of utxo-based privacy protocols, if only to align on terminology.

You can skip to the next section “Prior Art”, if you want.

Deposits

Conceptually, a deposit looks something like this:

A user deposits some public tokens into the system, and a note containing the deposited amount and an owner (an address or some public key) is created. The note serves as a representation of the user’s ownership of the underlying tokens, which are held by the system in a pool until the eventual owner chooses to withdraw or transfer some balance.

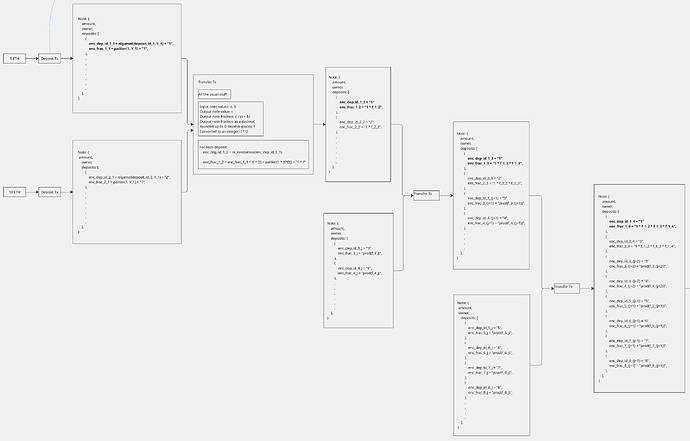

If you want more detail, here’s a more detailed diagram which illustrates a deposit process. Different implementations differ around the edges in many ways, but the crux is this.

Transfers

Conceptually, a transfer looks something like this:

A sender spends (or “nullifies”) two of their notes, creates a note for the transfer recipient, and creates a change note for themselves. Two notes are destroyed, two nullifiers are emitted, and two new notes are created and emitted.

Am I going to be bold enough to not explain what a nullifier is? I think I am!

Ah, actually, I’ll need to say the following about nullifiers because it’ll help me criticise an approach in the next section:

Nullifiers are used in private payment protocols to break the link between the tx which created a note and the tx which later spends that note. Without this “tx unlinkability” property that nullifiers provide, the whole transaction graph is visible to observers, and users can glean information that oughtn’t be leaked.

For the rest of this doc I’ll ignore nullifiers from diagrams, because they just cause clutter. If you see a note being fed into a circuit, assume it is being nullified.

Also, I’ll ignore the change note from diagrams to reduce clutter:

De-cluttered: no nullifiers are shown; no change notes are shown.

Withdrawals

Conceptually, a withdrawal looks something like this:

A user burns a note containing some value, and the system – which holds all publicly deposited funds whilst users transact privately within the system – transfers that value to the user’s specified address.

Prior art

As is traditional in papers, before we can dive into the detail of the new idea, we have to brutally criticise all existing ideas so as to justify this document’s existence.

I’ll be gentle though, because:

- Existing ideas are actually pretty good, and have been turned into actual working products with actual pmf. That’s awesome.

- You never know when you might end up working with someone in future;

- My idea might contain bugs;

- Even if the idea isn’t buggy, I can think of some brutal criticisms which I’ll share as we go, and which you might already be thinking.

Stay with me.

All of the products seek some form of compliant private tokens. Some are simple deposit-withdraw schemes, and some are deposit-transfer-withdraw schemes. They all essentially follow the approach outlined in the “Background” section, but with different approaches to cope with bad actors.

Payy

When you say the name of this product verbally, you have to say “Pay with two y’s” or you’ll be met with blank stares. Or you have to say “Payyyyyyy” and really stress the pronunciation.

Payy is a deposit-transfer-withdraw protocol.

Payy takes a very pragmatic and simple approach to cope with bad actors: they do away with nullifiers from their protocol:

Harking back to the basics of shielded protocols, nullifiers provide “tx unlinkability”. Without nullifiers, the input notes to a transfer tx are publicly visible. I.e. the output note of every tx can later be observed as the input note to some other tx. This means on Payy the entire transaction graph is observable.

If a bad deposit enters the system, you can trace exactly where that money flowed, and you can see which withdrawals from the system are descended from it. The recipient of a note can immediately identify that a note is downstream of a bad deposit, although they won’t know how much of that deposit contributed to their note.

So Payy sacrifices some privacy to enable traceability of bad actors. Let’s talk about the extent of the privacy sacrifice.

Off the top of my head, here are the privacy leakages that Payy’s design introduces:

The first transfer after a deposit is publicly identifiable as coming from the depositor. I.e. the sender is leaked.

The last transfer before a withdrawal is publicly identifiable as being to the withdrawer. I.e. the recipient is leaked.

If A deposits, then A → B (read: “A transfers to B”), then B withdraws, the world sees that A transacted with B. The world might even learn the exact amount that A sent to B if there were no other transactions in that subgraph.

If E → B → C → E, then E learns that B and C transacted. E learns that B knows C. That’s an unexpectedly large leakage. Love affairs have probably come to light with that much leakage.

If E is a large entity such as an exchange, they might be able to infer a significant amount of the transaction graph from this kind of leakage. They could piece together who knows who, and potentially deduce the amounts being paid between participants.

Those are leakages that I’m seeing from 5 minutes thinking about it. Some advanced team of nerds might be able to infer more.

Railgun

Railgun is a deposit-transfer-withdraw protocol. Very nice.

There is a one-hour delay on all deposits into the system, so that ‘bad’ deposits may be rejected.

Once in the system, money can be privately transferred between users.

The problem – and it’s the main problem prompted me to explore and write this entire post – is that one hour isn’t a very long time, and it’s technically possible that a bad actor could ‘slip through the net’ and deposit ‘bad’ funds into the pool. Once in the pool, there would be no way to catch them.

Edit after writing all this: It happened!!!

https://x.com/dethective/status/1994397800847589736?s=20

If only I’d finished this doc before it happened. I’d have been seen as prescient.

Anyway, I set out to solve the problem of tracing ‘bad’ funds through a pool which enables private transfers, even if we don’t know the funds are ‘bad’ when they enter the pool, whilst preserving as much privacy as possible for all users. I’ll be more rigid about requirements after I mention a few more projects.

EYBlockchain

Back in 2019, I was in a small research team that explored this problem: How to design a privacy pool where bad deposits could be traced – all whilst ensuring good privacy.

I recall for a while we went down the obvious – and today well-known – dead end of ascribing a deposit_id to every newly deposited note. Then, with each transfer, the output note would contain the union of all deposit_ids of all the input notes. This leads to an exponentially growing list, which ~doubles in size with each transfer. It’s not a sustainable approach. I don’t think we published anything.

Actually, I did do some public talks in 2019 which solved the easier problem of tracing a stolen NFT through a shielded pool of NFTs. The non-fungibility of NFT transfers means you don’t get the exponentially growing list problem.

There was a lot of ahead-of-its-time research in that small team, but we didn’t publish the half-baked ideas, which is a shame in hindsight.

However… see later in this doc where we try to resolve that problem by occasionally bootstrapping (resetting) that list.

A common criticism of any approach that tracks deposit_ids is that notes cease to be fungible: the deposit_ids serve as markers on the notes. People will be able to see patterns in the notes they send and receive.

A trivial leakage is Eve->Bob->Eve, or Eve->Bob->Charlie->Eve. Or even Eve->…->Eve. Eve will be able to spot the common deposit_ids in the notes she sent and the notes she received, and she might be able to infer information from that. E.g. in the case of E->B->C->E, Eve can infer that Bob knows Charlie, and that Bob sent Charlie money.

This doc tries to solve this problem – of deposit_ids serving as markers – by re-randomising the list of deposit_ids with every transfer. This way, Eve would not be able to identify any commonality between the notes she sent and the notes she later receives.

Privacy Pools

The Privacy Pools product is a deposit-withdraw protocol.

My first criticism would be “It doesn’t support transfers”, but the Privacy Pools paper does talk about an approach that would enable private transfers.

Edit after chatting with them at devconnect: v2 of Privacy Pools apparently will enable private transfers, but it’s different from the approach explained in the privacy pools paper. Here’s my understanding of what they’re building for v2:

For every deposit, the resulting note will contain a deposit_id. Transfers can happen within the system, but all the input notes must have the same deposit_id, and all output notes are given that same deposit_id.

It’s certainly a neat way of avoiding the “exponentially growing list” problem: a note will always contain 1 deposit_id.

A problem with this approach might be as follows. If a user needs to send 100 ETH, they will need two notes with the same deposit_id whose values sum to >= 100. But what if they don’t have two notes with the same deposit_id? They’d need to send multiple transactions; one for each distinct deposit_id of the notes they intend to spend.

Correction: the folks at Privacy Pools informed me that their transfer circuit will actually enable multiple input notes, all with potentially different deposit_ids, meaning you’ll be able to spend in a single tx. Each output note will still only contain one deposit_id.

Another problem: I suspect with sufficient deposit activity, it will become uncommon for a user to receive notes that contain the same deposit_ids. If that were true, it would therefore be uncommon for a user to join together two notes (since they must share the same deposit_id). And I suspect this could lead to a system which tends towards “dust”; where notes contain tiny and impractical values, since “split” operations would far exceed “join” operations.

Perhaps users could interact: a would-be recipient could request notes containing certain deposit_ids from a sender; a bit like the card game Go Fish: “Got any deposit_id = 1234?”.

The proposal in this post seeks to enable deposit_ids to be intermingled.

Another criticism of this v2 approach is – as mentioned in the previous subsection also – that deposit_ids serve as markers which spoil fungibility. This doc seeks to solve this problem by re-randomising the deposit_ids with every transfer.

My second (weaker) criticism of privacy pools is that there’s a variable-length delay before a deposit is accepted into the pool. Maybe that’s fine, but since I wanted to explore what happens if bad funds get into the pool, I don’t want the answer to be “just wait longer to perform more due diligence”. I’ll claim that maybe the due diligence process could make mistakes, and we’d like to be able to retroactively flag bad deposits as bad even if they’re accidentally let in.

The approach described in the privacy pools paper is as follows:

A criticism would be that there’s arguably too much information leakage; information that shielded pools traditionally like to keep private. Lots of private data is being shared between users, here, until the deposits are finally whitelisted.

Blanksquare

You probably won’t believe me, but I started writing the ideas of this post in September/October. I just got a bit busy with other things, like my day job, a delightful family holiday, and devconnect.

Then, whilst I was a +1 at a wedding on Saturday (late November), I got sent this link in a Signal group:

https://ethereum-magicians.org/t/shielded-pools-with-on-chain-retroactive-anonymity-control/26735

It suggests encrypting deposit_ids – an idea which also features this doc. Great minds!

Anyway, I’m not copying; they’re independent realisations of the same thing. I have timestamped receipts!

This doc expands on that idea much further, so I hope you’ll find it interesting. It also plugs some of the criticisms of that idea, which we’ll touch on now.

Briefly, the idea was for some entity to generate a new keypair for every deposit into the system. Each deposit_id could then be encrypted with its corresponding public key. Any later, corresponding withdrawal from the system would be forced to signal the same encrypted deposit_id (which would be salted so that the withdrawal signal looks unrelated from the deposit). On the happy path, observers would never learn that the withdrawal relates to the deposit. But if a deposit is later deemed ‘bad’, the secret key could be revealed by the holder of the decryption keys, which would enable all observers to decrypt the encrypted deposit_id of both the deposit and withdrawal transactions, and ultimately link the withdrawal to the deposit.

Problems with this approach:

The holder of the decryption keys is a point of failure for the system. If the keys are leaked (intentionally or otherwise), then people will be able to link all deposits and withdrawals of all users. There are suggestions to use TEEs or to secret-share the decryption keys through a collective of MPC nodes. Certainly, secret-sharing of decryption keys (and of other secrets) is a common approach that you’ll find in FHE and CoSnark settings, so some might consider this acceptable.

Vitalik certainly doesn’t like the notion of “rugpulling privacy”:

The approach I suggest in this post still has a controversial MPC collective who generate keys, but I try to greatly stem the worst-case leakage in the event that all of the decryption keys are somehow leaked.

With the Blanksquare approach:

- What is leaked, in the worst case?

- Every withdrawal is linkable to every deposit.

- Who is it leaked to?

- Everyone in the world (every blockchain observer).

With the approach in this doc:

- What is leaked, in the worst case?

- The deposit_ids that contributed to a given user’s note.

- The amount of each deposit_id that “contributed to” the note.

- Who is it leaked to?

- Only to the owner of the note.

The leakage is localised.

Not terrible, eh?

At least we’re not rugpulling privacy to the extent that would make Vitalik sad (I hope).

In the worst case, the protocol in this doc collapses to the approach where a note owner can see the deposit_ids that contributed to their note. It’s not ideal (see earlier sections which complain about deposit_ids serving as non-fungible “markers” on notes), but it felt like an advancement worth describing to you all.

In the happy case, privacy is actually quite nice.

The idea

Finally we can discuss the idea.

Requirements

What features is it seeking:

- A shielded pool that supports private transfers.

- On the happy path, deposit_ids (within notes) are randomised, to prevent advanced note owners from using them as “markers” to spot patterns in activity.

- If a bad deposit is accidentally allowed into the pool, it can be later flagged as ‘bad’, and all users of the pool can identify: whether their note contains any ‘bad’ value, and how much of their note’s value is deemed ‘bad’.

- Even in the worst case (of leakage of this protocol’s decryption keys), blockchain observers do not learn whose notes contain ‘bad’ value.

- Avoiding retroactive privacy rugpulls of historic withdrawals: This system can be designed to not leak information for withdrawals that already took place, even in the worst case of the system’s decryption keys being leaked.

- When performing a transfer or withdrawal, a user can prove that their input notes are not descended from ‘bad’ deposits.

- If a user’s note is descended from a bad deposit, the user can ‘decontaminate’ their note by splitting it into ‘good’ and ‘bad’ notes.

- I make no promises relating to constraint counts

High level

The low-level section is next

The basis is a simple deposit-transfer-withdraw protocol.

A blacklist of bad deposit_ids is maintained by some Blacklist Maintainer.

There can be a delay period before deposits can enter the set, but we’re interested in machinery to catch deposits that slip through such a delay period.

In a huge preprocessing step, a long list of deposit_id keypairs is generated: one for every future deposit into the protocol.

[(x_1, Y_1), (x_2, Y_2), ..., (x_{1000000}, Y_{1000000})]

where the x_i's are secret keys and the Y_i's are public keys.

The list can be periodically replenished whenever it runs low.

The list could be generated by a single actor, but you probably won’t like the sound of that very much, so let’s say the list is generated by a large MPC collective. Let’s call them the Key Holder(s). The Key Holders could be the same as the Blacklist Maintainer, or they might be different entities. We’ll come back to this worrying topic soon.

When a new deposit i is made, it will be publicly associated with public key Y_i.

A pre-generated list enables a user to deposit non-interactively into the protocol without waiting for the Key Holders to generate and publish a new public key.

We will encrypt information to this public key Y_i. Specifically, every note that is “downstream” of this deposit will will contain:

- An encryption of the deposit_id i, encrypted to Y_i;

- An encryption of the fraction of that deposit that contributed towards this note, encrypted to Y_i.

We’ll go slowly through the technical details in a later section.

Since this system supports transfers, a note might be the descendant of multiple deposits. That’s ok: the note will contain the list of all upstream deposits. Astute readers will be notice that such a list would grow exponentially and unsustainably – doubling with each transfer. We’ll come back to this later.

Under normal circumstances, the owner of a downstream note will not be able to decrypt the encrypted deposit information that is contained within their note, because nobody (hopefully not even the collective of Key Holders) knows the decryption key x_i, and so they won’t know which deposits have flowed into their note. The aim is for the privacy of the system to be as close to zcash as possible, where observers don’t know what’s happening inside the pool, the tx graph is not known, value is fungible, and the owners of notes can’t trace their notes’ lineages.

If deposit i is later deemed to be “bad”, then the Blacklist Maintainer will flag deposit i onchain. Upon seeing i get blacklisted, the Key Holder(s) are tasked with revealing the corresponding secret key x_i onchain. If the Key Holders are an MPC collective, they’ll need to work together to learn what x_i actually is, e.g. through some threshold scheme.

This publication of i and x_i will trigger a flurry of activity: All note owners in the entire system can attempt to decrypt all of the encrypted deposit_ids that are contained within their notes. If their note is a descendant of deposit i, then they will successfully decrypt one of their note’s encrypted deposit_id fields to yield i.

Let’s suppose their note does contain “bad” funds from deposit i. Uh oh. To learn how much, the revealed x_i can also be used to decrypt the corresponding “encrypted fraction” that exists within their note. This will reveal what fraction of the original deposit is deemed to be contained within their note.

A new and dramatically-named “decontamination circuit” will enable the user to “carve out” the bad funds from their note.

It’s important to note that a note owner won’t be able to decrypt any of the other encrypted deposit_id fields of their note. All that will have been leaked to the note owner is:

“My note is ‘downstream’ of deposit i; the protocol considers my note to contain X amount from that bad deposit”.

Or, more succinctly:

“X amount of my note is considered to have originated from bad deposit i”.

The note owner won’t learn any other information about their note’s lineage, including who the value passed-through before it reached them.

Outside observers won’t learn which notes are contaminated, and won’t learn meaningful information about the tx graph.

By this point, there are probably some burning criticisms raging in your head. Let’s list some:

- If the Key Holders collude, they could learn the x_i's.

- The Blacklist Maintainer might turn evil and censor people by adding them to the blacklist.

- The Key Holders might not do their job of revealing x_i once i is blacklisted.

- It doesn’t seem fair for an honest user to receive a note without being able to see which deposits have contributed to it, only to later discover (upon a blacklisting event) that their note is actually contaminated with some “bad” value.

- How does the protocol determine what proportion of a deposit flows into each note?

- If you track a list of deposits, then it will double with every ‘transfer’ tx. That’s not sustainable.

We’ll talk about all that soon.

Step by step

Setup

In a huge preprocessing step, a long list of deposit_id keypairs is generated: one for every future deposit into the protocol.

[(x_1, Y_1), (x_2, Y_2), ..., (x_{1000000}, Y_{1000000})]

where the x_i's are secret keys and the Y_i's are public keys.

The list can be periodically replenished whenever it runs low.

Slightly more formally (but still being pretty loose with notation):

G \in \mathbb{G} a generator point.

x_i \in \mathbb{F} a secret key for deposit_id i, in the scalar field of the group \mathbb{G}.

Y_i := x_i \cdot G the corresponding public key for deposit_id i.

Deposit

A user deposits some amount as part of deposit i. This deposit is associated with public key Y_i.

A new note is created, containing this data:

notes[i][1] = {

owner,

amount,

randomness,

deposits: [

{

encrypted_deposit_id = "i",

encrypted_fraction = "1",

},

{},

...

{}

],

}

where:

we’ll sometimes use the notation "x" to lazily mean “the encryption of the value x”.

encrypted_deposit_id = "i" = \text{enc}_{Y_i}(i), an encryption of the deposit_id i, encrypted to the public key Y_i.

This encryption scheme must support re-randomisation of ciphertexts. Elgamal is a good choice (see the Appx).

encrypted_fraction = "1" = \text{enc}_{Y_i}(1), an encryption of the fraction of this deposit that has flowed into this note, which is initially an encryption of 1.

This encryption scheme must support scalar-multiplication of a ciphertext by a known scalar. We’ll explain why in a sec. Paillier encryption is a cool choice, but it’s quite inefficient within a snark circuit (see the Appx).

DIAGRAM TIME!

enc_dep_id_i_jis the “encrypted deposit_id” of depositiafter thejthhop (transfer) from the deposit.

enc_frac_i_jis the “encrypted fraction” of the value of depositithat has contributed to this note (after thejthhop (transfer) from the deposit).

Users won’t actually seej; it’s just to help diagram readers.

Paillier encryption isn’t set in stone; there are apparently much more-efficient alternatives for multiplication of a ciphertext by a known scalar.

Recall, I’m using quotes for legibility and laziness:"x"means “the encryption ofx”.

Transfer

Example

A private transfer destroys two notes, and creates one for the recipient and a change note for the sender. (We’ll ignore the change note for brevity).

Suppose our original depositor of 5 ETH wants to send 1.5 ETH to someone.

Suppose – along with their 5 ETH note – they have a 10 ETH note.

They can nullify those two notes – collectively worth 15 ETH – and create a new note worth 1.5 ETH.

How much of the 5-ETH-deposit and how much of the 10-ETH-deposit ended up inside the new 1.5-ETH note?

It’s actually difficult to say how much of a deposit contributes to a downstream note, given the fluidity of money. It’s like trying to figure out how much of a tomato contributed to a particular spoonful of soup.

But there is a mathematically-natural approach one can take, and that’s to deem the contributions to be proportionate to the input notes.

In our example, we can deem that 5 * \frac{1.5}{15} = 0.5 came from the 5-ETH-deposit, and 10 * \frac{1.5}{15} = 1 came from the 10-ETH-deposit. In other words, we can apply a fraction of \frac{15}{150} to both of the input deposits.

In theory, a user could attribute contributions differently: e.g. allocating all of a particular deposit_id into their change note, and none of it into their intended recipient’s note. But since our protocol hides which deposit_ids are contained within a note (in the case that the deposit_id is ‘good’), there’s really no point; the user wouldn’t know which deposit_ids they’re even allocating! And in the event that a deposit_id is learned to be ‘bad’, there’s a separate decontamination circuit that can separate-out the ‘bad’ value.

This diagram illustrates how fractions can be applied to the deposit_ids that contributed to a particular note:

Recall, I’m using quotes for legibility and laziness:

"x"means “the encryption ofx”.

We can consider a subsequent transfer which takes as input this 1.5-ETH note. Suppose we’re transferring 20 ETH, and the other input note has 100 ETH in value.

Then the next fraction to apply to all deposits that contributed to the 20-ETH output note is: \frac{200}{1015}.

Notation within a diagram is always cumbersome.

You can see I got lazy with the notation within that 100-ETH note. E.g.

enc_frac_3_j = "prod(f_3_j)"is notation to mean “the encryption of the fraction of deposit 3 that contributed towards this note”. And we’ll lazily say there werejtransfers since deposit 3 to get to this note".

If you look at the 20-ETH note, it should start to show the pattern of the deposit data that we’re tracking.

The data being tracked for the 5-ETH deposit is:

deposits: [

(

enc_dep_id = "1"

enc_frac_1_3 = "1 * (15/150) * (200/1015)",

),

Now, the owner of this 20-ETH note can’t actually decrypt these ciphertexts enc_dep_id_1_3 and enc_frac_1_3, because they don’t know the decryption key x_1.

But if suddenly the Blacklist Maintainer were to blacklist deposit 1, and if the Key Holder(s) did their job of then deriving and publishing x_1, then the holder of this 20-ETH note would be able to decrypt ciphertexts enc_dep_id_1_3 and enc_frac_1_3. (Note: they would still not be able to decrypt the other ciphertexts that are stored within their note, because they each are encrypted to different public keys).

The note owner would learn “Oh look, I was able to use the newly-published x_1 to decrypt enc_dep_id_1_3 to yield 1, implying that my note is ‘contaminated’ with some value from deposit 1. I’ll now decrypt enc_frac_1_3 to yield the fraction 1 * (15/150) * (200/1015). I know how much was deposited as part of deposit 1 (because deposit amounts are public): it was 5 ETH. So I’ll compute 5 * (1 * (15/150) * (200/1015)) = 0.098522 ETH. Therefore the protocol deems 0.098522 ETH of my note to be from the ‘bad’ deposit 1.”

Ignoring any criticisms in your head: that’s pretty cool, right? A load of gibberish, unintelligible, encrypted data can exist within hundreds of notes in the network, without leaking the transaction graph, and then suddently a blacklisting of a deposit can reveal a very thin slice of useful information, and only to the owners of downstream notes.

Paillier

We can encrypt the fraction using Paillier encryption, so that we can repeatedly multiply the resulting ciphertext by a new fraction with every future transfer transaction, without ever learning what the resulting fraction is.

I.e. if I give you enc(m), you can compute enc(km) for a known scalar k, without learning what m is.

See the Appendix for a huge explanation of Paillier encryption. Independently of the rest of this doc, it’s really cool. Apparently there are much more efficient approaches to achieve this “scalar multiplication” property within a snark using FHE schemes. Interested readers can explore those ![]()

Looking back at our ongoing example, we started with:

enc(1)

The next transfer circuit scalar-multiplied this ciphertext by a known scalar 15/150 (represented as an integer rounded to 6d.p. as 15/150 * 10^6 = 100,000). If using Paillier, the operation would be enc(1)^{100000} = enc(1 * 100000). The recipient of the note won’t know which deposit_id(s) flowed into the note, nor will they learn what fraction of each deposit_id that contributed to their note: they’ll just see the newly computed ciphertext.

The next transfer circuit scalar-multiplied this ciphertext by a known scalar 200/1015 (represented as an integer rounded to 6d.p. as 200/1015 * 10^6 = 197,044. If using Paillier, the operation would be enc(1 * 100000)^{197044} = enc(1 * 100000 * 197044).

When decrypted, the true fraction can be derived as 1 * 100000 * 197044 / (10^6)^2 = 0.0197044

If the decryption key is ever revealed, the user will be able to decrypt this fraction and apply it to the original deposit amount (in our example 5 ETH) to discover that their note is deemed to contain 0.0197044 * 5 = 0.098522 ETH.

Some comments on the Example

Some comments before we go further.

Fractions → Decimals

In the diagrams, we were tracking encrypted fractions, but we don’t actually want to do that for two reasons:

Encrypting a fraction, and iteratively multiplying-in new fractions, would require both the numerator and denominator to be encrypted separately (at least with the encryption schemes I’m familiar with), and that’s a waste of constraints.

The numerator and denominator of a fraction are leaky:

The numerator can be factorised to infer the possible amounts that were transferred with each ‘transfer’ tx since the deposit. The denominator can be factorised to infer the sizes of the notes that were held by each intermediate note owner since the deposit.

Instead, we can convert each fraction into a decimal, which can be (crucially and necessarily) rounded to a certain number of decimal places. The rounding reduces the amount that can be inferred through factorising (especially if users make interesting choices of transfer amounts, such that the resulting fraction does incur rounding).

Why are the deposit_ids being encrypted at all?

Suppose Eve sends to Bob, who sends to Eve (E → B → E). If the deposit_ids aren’t encrypted, then Eve would notice the common deposit_ids between the note she sent and the note she received.

Possibly worse, suppose Eve sends to Bob, who sends to Charlie, who sends to Eve (E → B → C → E). If the deposit_ids aren’t encrypted, then Eve would notice the common deposit_ids of the note she sent to Bob and the note that Charlie sent to her. Eve might deduce things like “Bob knows Charlie” and “Bob sent money to Charlie” and possibly even the amounts that they sent to each other. That’s leakiness that we can avoid by re-encrypting the deposit_ids.

But if the encrypted deposit_ids don’t change between transfers, then those ciphertexts effectively become alternative identifiers for the deposits.

That’s why we re-randomise the encrypted deposit_ids with every transfer. This way, the list of deposit_ids is a different list of random-looking numbers in every single note! It’s why Elgamal is a nice choice of encryption scheme. See the Appx for how Elgamal and re-randomisation work.

Why are the fractions (or decimals) being encrypted at all?

It’s similar to why the deposit_ids are encrypted.

An entity who appears multiple times in the tx graph might spot patterns in the fractions contained within their notes, and piece-together the tx graph, or make inferences similar to the above sections.

It’s bad that the user got rugged of 0.098522 ETH, in the example

In the example, a portion 0.098522 ETH of the user’s note was deemed ‘bad’, some time after the user came into possession of the note. The user is honest and wasn’t aware of the ‘badness’ of the note when they received it.

Ideally, the blacklisting would happen before any transfers happen in the system, e.g. during a deposit delay period. In such cases, the secret key x_i for the bad deposit would already be known to all users before any transfers can occur. If the baddy tried to transfer money to an honest user, that user would be able to tell straight away.

Also, there’s an interesting rabbit hole of what should happen in the real world analogue of this situation. Imagine a bank robber steals $1m and then starts spending it. If some of those dollar bills are found to have ended up in the hands of an unaware and innocent person, what should happen to those tainted bills? Is the person allowed to keep the money, or do they have to give it back to the bank?

Apparently there’s a precedent in Scotland that the person would be allowed to keep the money. If anyone knows what would happen in other jurisdictions, that would be interesting!

Comfortingly, I believe privacypools v2 will also suffer from this property: If a deposit is later flagged as being ‘bad’, an honest user could be left holding a note that contains bad value. (It’s comforting in the sense that another team has accepted this downside).

Exponentially growing list of deposit_ids

The number of deposit_ids inside a note doubles with each transfer. That’s bad. After 64 transfers, a note would contain a list of 2^{64} deposit_ids. Not sustainable. That’s far more items than the number of deposits, and is far more than a device can possibly store!

We need to do some kind of bootstrapping to “reset” these lists once they grow to a certain size.

If each of the deposit_ids wasn’t encrypted, we might have been able to identify and remove duplicate entries from the list, but that wouldn’t suffice: the lists would still be unbounded in size, which isn’t compatible with circuits.

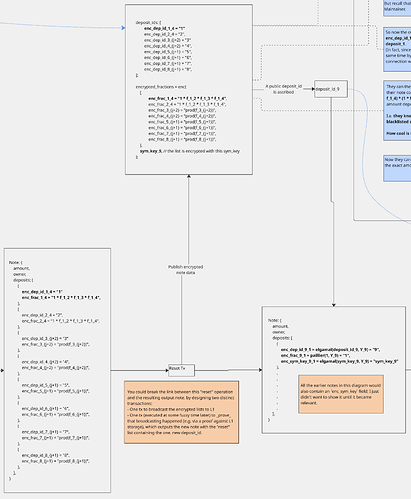

Reset Tx

Let’s do this:

We establish a max size for the list within a note to be, say, 64. If two candidate input notes to a circuit have lists whose concatenated size would be larger than 64, the transfer circuit would disallow those input notes. We would require the owner of such a note to execute a “reset” circuit, which:

- publishes a re-randomised encryption of the list to L1

- establishes a new “deposit_id” for this reset action

- creates a new note containing that single, new deposit_id.

This effectively resets the list from “up to 64 items” to 1 item.

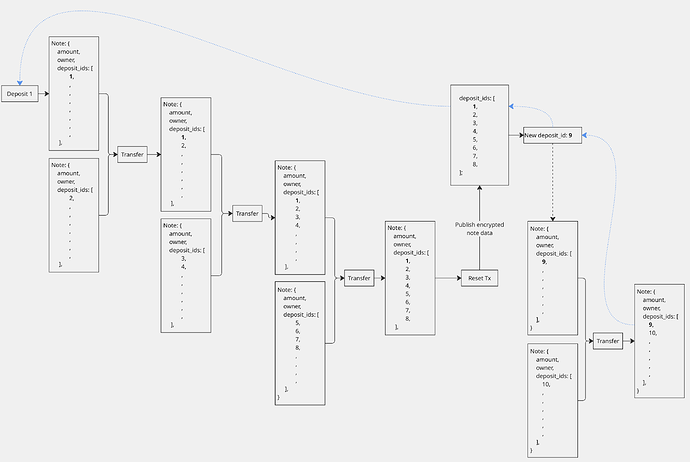

There’s a bigger diagram that illustrates this:

Suppose we have a note whose list of encrypted deposit_ids has reached max capacity:

We can execute the “reset” circuit, which publishes a re-randomised encryption of the list to L1:

There’s quite a lot to explain here.

The “reset tx” publishes the saturated list of re-encrypted deposit_ids. It’s important to re-encrypt, so that the person who created that note can’t see that you’ve chosen to reset your note.

In the worst case (if the anti-collusion assumption doesn’t hold) the Key Holder(s) can technically decrypt the published list of deposit_ids to learn “Someone has ‘reset’ some note which is downstream of these particular deposit_ids”. The Key Holders wouldn’t be able to learn: which note is being reset; the value of the note; the owner of the note. I’d say that’s not a terrible worst-case leakage.

In this worst case, the person who created that note in the first place would spot that this decrypted list matches the list contained within the note they sent to you, and hence they’d infer that you’d reset your note. But this isn’t new information: if the list of an output note is saturated, it’s obvious that the recipient of the note would need to reset it. In the best case, these lists look unintelligible.

In addition to the list of re-encrypted deposit_ids, the reset tx also publishes a list of re-encrypted fractions. This list is further encrypted by a symmetric key.

Why do we encrypt a list of already-encrypted information?

I was trying to hide as much as possible from the Key Holder(s) in the worst case that they collude: Even if the Key Holder(s) turned malicious and tried to decrypt this list, they wouldn’t have the extra symmetric key, and so they wouldn’t be able to decrypt this list.

The symmetric key is chosen by the user who executed this “Reset Tx”, and it is henceforth passed-along through all downstream notes. You can see in the diagram that the output note contains an enc_sym_key field. To avoid users using this symmetric key as a “marker”, the symmetric key is itself encrypted using the Key Holders’ public key that corresponds to this Reset Tx (i.e. the public key Y_9 in the diagram).

Ok, so this is a bit weird. We sought to hide a list from the Key Holders, so we encrypted that list with a symmetric key that they don’t know, but then we encrypt that symmetric key with another of the Key Holders’ keys. If the malicious Key Holders ever come into possession of a downstream note of this “Reset Tx”, they will have enough information to decrypt the list of encrypted fractions that we sought to hide. But again, the Key Holders’ ability to decrypt the list of published fractions is only in the worst case that they collude to leak their secret keys. The leakage in this worst case is a bit more severe: the Key Holders would be able to use the decrypted fractions to learn how much value was contained within the note. I.e. they’ll learn “Someone (we don’t know who) has reset some note (we don’t know which note), and it contained [some known amount of ETH].”. That’s not great. It’s why I did the spaghetti to encrypt the list from the Key Holders (with dubious success). This is the part of this protocol that really leans on the hope that the MPC collective won’t collude.

You can think of the worst case leakage being like invisible flying fish. Occasionally (every time there’s a reset) the malicious Key Holders would hear a fish leap out of the water (they don’t know which fish) and shout “value = 8”. They’re talking fish.

A small detail: there’s an orange box that describes an idea that I like: the tx which publishes the saturated list of encrytped deposit_ids should be separated from the tx which emits the new note. It just gives a small improvement in the privacy of the output note.

Blacklisting

What does the act of blacklisting look like?

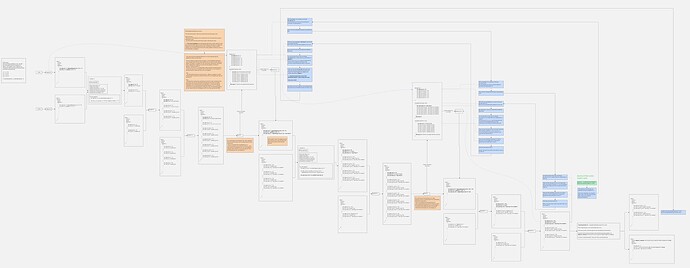

The big diagram does a much better job of illustrating this: Miro

For every deposit into the system, the Blacklist Maintainer would do some due diligence checks to see if the source of funds for the deposit is ‘bad’.

If the deposit is bad, they’d add its deposit_id to their blacklist.

Ordinarily, the deposit won’t even have been allowed into the system. All the fun complexity of this doc only triggers if the bad deposit is allowed into the system before it’s identified as ‘bad’, and is only later identified as being ‘bad’. So let’s explore that case.

Upon seeing this blacklisting, the Key Holders would then reveal the decryption key that corresponds to this ‘bad’ deposit_id.

Upon seeing a new decryption key get published, the owners of all notes would attempt to decrypt each item in their note’s list of deposit_ids. If decryption of any item succeeds, the user would know their note contains some value that descended from the ‘bad’ deposit.

Upon successful decryption, the user can decrypt the corresponding encrypted fraction. This will reveal the fraction of the original deposit amount that is contained within their note.

The user can execute a ‘decontamination’ circuit, to split their note into two: the good value and the bad value.

If one or more Reset Txs have taken place between the deposit and the creation of the user’s contaminated note, then their note won’t contain an encryption of the original deposit_id: it will contain an encryption of the ‘deposit_id’ of the latest reset tx. If the owner of such a note were to try to use the revealed decryption key on any of the items in their note’s list of deposit_ids, the decryptions would not be successful because they don’t have the decryption key for the latest reset tx. What can we do?

The Key Holders would also need to reveal the decryption key for that latest reset tx. After having collaborated to reveal the decryption key of the initial bad deposit_id, they can scan all of the published data of every Reset Tx, and attempt to decrypt each of the deposit_ids contained within that published data. If they get a match, they will know “This reset tx is resetting a note that contained this ‘bad’ deposit_id”. They can then further reveal the decryption key that corresponds to the deposit_id of this Reset Tx. Note owners of notes that are downstream of this Reset Tx can then realise that their note is indeed far-downstream of a bad deposit_id.

If multiple Reset Txs have happened, the Key Holders will need to repeat this process iteratively to reveal the decryption keys for the deposit_ids that correspond to all reset txs along this path.

Observers will see: A bad deposit led to a deposit-id-decryption-key being revealed, which then led to a cascade of reset txs’ deposit-id-decryption-keys being revealed. They still won’t be able to decrypt the other encrypted items that are published as part of a reset tx: not the other encrypted deposit_ids, nor any of the encrypted fractions.

Then, a note owner whose note is far downstream will be able to decrypt the deposit_id of the most recent reset tx.

The note owner can:

- Decrypt one of the deposit_ids contained within their note.

- Realise that it’s associated with a recent reset tx.

- Quickly realise why the deposit_id that corresponds to this reset tx was revealed: it’s because of a particular bad deposit_id.

- Quickly realise the list of all decryption keys that were revealed by the Key Holders as a result of the bad deposit_id – i.e. those of the deposit and of all reset txs that are downstream of that deposit.

- For the most recent reset tx:

- Attempt to decrypt every encrypted deposit_id that was published as part of that reset tx.

- If a decryption succeeds, this reveals the deposit_id of the next-most-recent reset tx along the path back to the bad deposit.

- Repeat for this next-most-recent reset tx.

- Eventually arrive at the bad deposit. The user will have a list of reset txs that lie along the path from the bad deposit to their note. They’ll also have the decryption keys of the bad deposit_id and of the deposit_ids of those reset txs. The user will not have the decryption keys associated with other encrypted deposit_ids nor of their encrypted fractions.

- The user can decrypt the encrypted symmetric keys along the path from their note to the bad deposit.

- The user can then use those symmetric keys to decrypt the encrypted fractions along the path to ultimately deduce how much of the bad deposit is contained within their note.

- Note: this will not leak the encrypted fractions of other deposits that contributed to the user’s note.

- Note: only downstream note owners will be able to do this.

- Note: external observers will not learn anything about the contents of a user’s note.

Stemming the cascade of revealed decryption keys

It’s a bit of a shame that a single blacklisted deposit_id can lead to a cascade of reset txs’ deposit_ids being revealed. Those reset txs’ decryptable deposit_ids can serve as markers on all future notes – the very kind of markers that we sought to remove with this protocol.

We could perhaps stem this leakage.

- If the value that the reset tx contributes to a given note is negligible, the user can execute the ‘decontamination’ tx to remove that value from their note.

- We could also allow any revealed deposit_ids whose value contributes a “negligible amount” to a note to be ignored when executing future reset txs. I.e. “I am resetting a note, I know it contains some contaminated value from some earlier reset tx, but it’s so negligible that the protocol is allowing me to ignore it and not publish its corresponding encrypted deposit_id”.

- We could allow deposit_ids of deposit txs (and of reset txs) to be removed from a note’s list if they’re older than, say, 1 month. Of course, such deposit_ids can only be removed if their decryption keys have been revealed: otherwise they would continue to look like random gibberish to the note owner.

What if theft happens within the pool?

We’ve attempted to cope with a theft that happens before value is deposited into the system. But what if the theft happens within the system?

I haven’t thought deeply about that.

I suppose every transfer could also append some kind of transfer_id to the list of deposit_ids contained within the output note. Then if a theft happens, the victim could complain and provide the transfer_id to the Blacklist Maintainer, who could then blacklist in the same way as for bad desposits. But then every transfer_id would need a corresponding encryption key – much like every deposit_id – but I’m not sure how they’d be assigned from the precomputed list of encryption public keys without causing race conditions between users.

Withdrawals

To withdraw from the system, a user can:

- Nullify their note;

- Prove that their note did not contain any blacklisted deposit_ids;

- This will require a recursive proof, because:

- The user’s note has multiple encrypted deposit_ids. The user needs to prove that if they attempt to decrypt their note’s list of deposit_ids with all of the protocol’s historically revealed decryption keys, they never get a successful decryption.

- Yes, this is inefficient and doesn’t scale well. It’s similar to Tachyon, where a user might need to have an ivc process running in the background, but this time to prove the goodness of their notes.

- If a user decrypts the deposit_id associated with a “reset tx” (rather than a proper deposit tx), the proof needs to recurse through the linked list of reset circuits all the way back to the original deposit_id.

- The user’s note has multiple encrypted deposit_ids. The user needs to prove that if they attempt to decrypt their note’s list of deposit_ids with all of the protocol’s historically revealed decryption keys, they never get a successful decryption.

- This will require a recursive proof, because:

We then hit an ethical dilemma that Vitalik warns against: we don’t want to rugpull people’s privacy if they’ve already withdrawn from the pool.

Our options are:

- Have the withdrawal tx reveal (to the world) the list of encrypted deposit_ids (which is effectively the rugpulling of privacy that Vitalik doesn’t like). This enables bad deposits to be flagged even after withdrawals have taken place. Or

- Don’t reveal the list of encrypted deposit_ids to the world, thereby retaining user privacy even after they’ve left the pool. The withdrawal circuit proves compliance against the current blacklist. The protocol accepts that any later blacklisting cannot catch already-withdrawn users.

- To improve upon this, a withdrawal delay (from the time of the latest deposit_id in the note’s list of deposit_ids) could be imposed by the withdrawal circuit. This gives the protocol more time to notice bad deposits and update the blacklist. Such a withdrawal delay isn’t terribly restrictive, given that the user is still able to ransfer within the protocol without delay.

The full picture

Checkout the entire diagram in full resolution here: Miro

It includes an explanation of what happens when a deposit_id is blacklisted, and all of the steps a user’s wallet will need to do to ascertain how much ‘bad’ value is contained within their note (if any).

Efficiency

I didn’t implement any of this to measure it; I just wanted to describe the high-level mechanism.

The elgamal re-encryption for all encrypted deposit_ids wouldn’t be too bad.

The paillier re-encryption would be pretty insane, constraint-wise. If you’re willing to let a user wait a few minutes, maybe it’s viable ![]()

Apparently there are more efficient FHE approaches to multiplying a ciphertext by a known scalar.

Pros & Cons

Pros

- Super fun.

- It achieves properties that I haven’t seen before: traceability of transfers through the pool, but in a way where deposit_ids don’t serve as markers that spoil privacy, because they’re re-randomised.

- For notes that don’t contain any bad value, notes are very fungible.

- For notes that do contain bad value, that value can be removed from the notes.

- Only if some contributing value is later identified to be ‘bad’, the note owner can identify how much of their note is ‘bad’.

- It gives good privacy if the Key Holders act honestly and don’t collude.

- In the worst case (where the Key Holders act collude), a user’s privacy is not rugpulled to the world nor to the Key Holders: only a small amount of metadata is leaked to some other note holders. The owners of notes and the values being transferred remain private.

Cons

- No one has validated this, so it might contain a mistake.

- Complex

- Inefficient circuits

- Ugly “reset” step

- Costly “reset” step – lots of ciphertexts being published to DA every few txs.

- Some metadata leakage to some other note owners if a deposit is blacklisted, and/or if the Key Holders collude.

- Doesn’t allow for multiple blacklisters for different jurisdictions. I imagine solutions will need to be able to cope with multiple blacklisters/whitelisters, and enable users to choose.

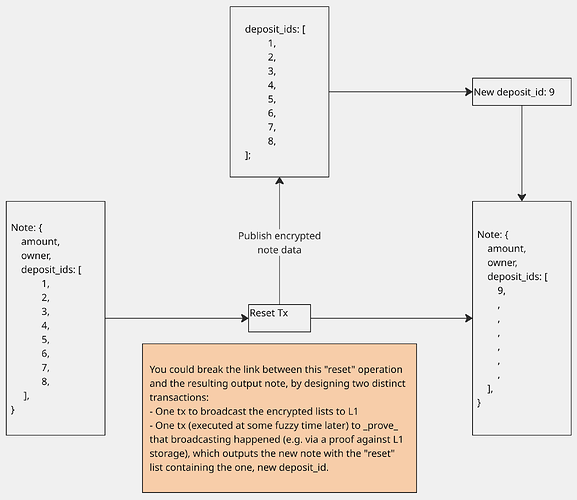

An alternative

If you don’t like the idea that information is being encrypted to a mysterious MPC collective of Key Holders, you could strip-away lots of the fun aims of this doc and still end up with an interesting protocol that gives some traceability:

Instead of seeking to randomise the deposit_ids of every note, you could simply pass-along the raw lists of deposit_ids with every note. You could then do away with the complexities relating to encrypted fractions. (It’s not as fun, though).

The “Reset Tx” could publish the raw list of deposit_ids, and a newly-reset note could be established with a new deposit_id. Subsequent notes would track this new deposit_id in their lists, until the list grows too big and another Reset Tx must be executed. The notes then effectively form a linked list, knitted together by reset operations.

Here’s an illustration of how a user would identify that their note is descended from a bad deposit with deposit_id 1:

Not shown in this diagram: the notes would need to track not only the deposit_id, but also the amount that each deposit is deemed to contribute towards this note.

The blue arrow shows how the owner of the right-most note (which contains deposit_id 9) would identify that their note is downstream of deposit_id 1. They would then be able to deduce the amount (not shown) of deposit_id 1 that contributed to their note.

Notice, though, that this act of resetting the list would also require publishing the constituent amounts that each deposit_id (ids 1-8) contributed to the note being reset, so that the owner of the right-most note has sufficient information to deduce how much of their note is contaminated. I haven’t shown the leakage of amounts in this diagram.

It’s for this reason that I still like the unhinged approach of re-encrypting everything, that this doc has explored.

There are valid criticisms to the leakage that comes from tracking raw deposit_ids, but it does massively simplify things.

Appendix

Elgamal

The encrypted message M_i can be some representation of i as a point. E.g. M_i = i \cdot G or M = Y_i or M = H2C(i). Whichever is secure.

Choose random r_{i, 1} \in \mathbb{F}.

Let:

R_{i, 1} = r_{i, 1} \cdot G.

S_{i, 1} = M_i + r \cdot Y_i.

The ciphertext is then a pair of points:

C_{i, 1} = (R_{i, 1}, S_{i, 1})

Decryption

Given the secret key x_i, compute:

M_i = S_{i, 1} - x_i \cdot R_{i, 1}

Note: S_{i, 1} - x_i \cdot R_{i, 1} = (M_i + r_{i, 1} \cdot Y_i) - x_i \cdot (r_{i, 1} \cdot G) = M_i + (r_{i, 1} \cdot x_i) \cdot G - (x_i \cdot r_{i, 1}) \cdot G = M_i

Elgamal

Elgamal supports efficient re-randomisation of a ciphertext.

The encrypted message M_i can be some representation of i as a point. E.g. M = i \cdot G or M = Y (if secure).

Choose random r \in \mathbb{F}.

Let:

R = r \cdot G.

S = M + r \cdot Y.

The ciphertext is then a pair of points:

C = (R, S)

Decryption

Given the secret key x, compute:

M = S - x \cdot R

Note:

S - x \cdot R = (M + r \cdot Y) - x \cdot (r \cdot G)

= M + (r \cdot x) \cdot G - (x \cdot r) \cdot G

= M

Re-randomising

We can take an elgamal ciphertext and re-randomise it. This means if Alice’s note contains ciphertext C, then she sends a note to Bob containing a re-randomised C’, and then Bob (or some owner of any later descendant note) sends Alice a re-randomised C’', then Alice will have no idea that her new note is a descendant of her earlier note or of the note that she sent to Bob. Very nice.

To re-randomise ciphertext C = (R, S) which has been encrypted to public key Y:

Pick random scalar r'.

Let:

R' = R + r' \cdot G

S' = S + r' \cdot Y

Then the new ciphertext C' is:

C' = (R', S').

To decrypt C' using secret key x:

M = S' - x \cdot R'

Note:

S' - x \cdot R' = (M + (r + r') \cdot Y) - x \cdot ((r + r') \cdot G)

= M + ((r + r') \cdot x) \cdot G - (x \cdot (r + r')) \cdot G

= M

Re-randomising, whilst hiding Y

But there’s a problem. To re-randomise, notice that you need to know the public key Y. But our goal of re-randomising is to hide which deposit this ciphertext relates to, but the public key Y is (by design) an identifier for the deposit!

So we also need to re-randomise the public key Y to some Y', so that the next person to re-randomise can do so without knowing which deposit they’re actually dealing with.

So when the first depositor computes C = (R, S), they also re-randomise the public key Y as:

Y' = \alpha \cdot Y for some random scalar \alpha.

They’ll also need to randomise the generator G accordingly, so that all terms can cancel when we decrypt.

G' = \alpha \cdot G

The initial depisitor sends a revised ciphertext of C = (R, S, Y', G').

The receipient will not be able to tell that Y' relates to Y. (See a section below exploring whether this is indeed the case…!).

The recipient will have confidence that Y' has indeed been computed with the same \alpha as was used to derive G', because a snark will have constrained their derivation.

Some time later, the new owner will want to re-randomise the ciphertext for their recipient.

We revise the definitions of our earlier points R' and S' to be:

Pick random scalar r'.

R' = R + r' \cdot G'

S' = S + r' \cdot Y'

Notice the usage of G' instead of G, and Y' instead of Y.

Choose random scalar \alpha'.

Y'' = \alpha' \cdot Y'

G'' = \alpha' \cdot G'

The re-randomised ciphertext becomes:

C'' = (R', S', Y'', G'').

To decrypt C^{(i)} using secret key x:

M = S^{(i)} - x \cdot R^{(i)}

Note:

S^{(i)} - x \cdot R^{(i)} = M + \sum_{j=0}^{i}(r^{(i)} \cdot Y^{(i)}) - x \cdot \sum_{j=0}^{i}(r^{(i)} \cdot G^{(i)})

= M + x\cdot\sum_{j=0}^{i}(r^{(i)} \cdot G^{(i)}) - x \cdot \sum_{j=0}^{i}(r^{(i)} \cdot G^{(i)})

= M

The user has been able to successfully re-randomise the ciphertext without knowing which public key this ciphertext has been encrypted to!

There is a slight danger to worry about. If I give you Y^{(i)} := (\prod_{j=0}^{i-1}\alpha^{(j)})\cdot Y and G^{(i)} := (\prod_{j=0}^{i-1}\alpha^{(j)})\cdot G, and you already know G and Y, can you figure out that Y^{(i)} relates to Y? I don’t want you to be able to: that’s the whole aim of this re-randomisation gubbins.

I have in mind that our group \mathbb{G} will be the Grumpkin curve, for efficiency reasons. Thankfully, Grumpkin is not a pairing-friendly curve. I was worried about an attacker learning the relationship between Y^{(i)} and Y by doing something like:

e(Y^{(i)}, G) == e(G^{(i)}, Y)

This hypothetical equality would indeed hold and hence would leak the relationship. But: Grumpkin is not pairing-friendly, and we haven’t even established any \mathbb{G_2} elements that could be fed-into such a pairing; all we’ve been using are \mathbb{G_1} elements. Indeed I’m not sure anyone’s bothered to find the embedding degree of Grumpkin, so we don’t even know how to express \mathbb{G_2} elements, and even if we did they would be (presumably) so astronomically huge as to be impractical.

So I think this re-randomisation approach works, but as I say: this isn’t a rigourous write-up. There could be mistakes, and hopefully someone on the internet will tell me the mistakes! Have I missed an easy attack that can relate Y^{(i)} to Y?

Paillier Encryption

Paillier encryption is really cool, so I explain it below.

The property we need is “multiplication of a ciphertext by a known scalar”.

I.e. if I give you enc(m), you can compute enc(km) for a known scalar k.

This is slightly easier to achieve than multiplication by an encrypted value enc(k).

There are a couple of options:

- Paillier encryption

- FHE

Interestingly, although Paillier encryption looks quite simple (see below), it’s actually a significant number of constraints to compute enc(km) from enc(m) and k within a circuit.

Surprisingly (for me who is a novice at FHE maths), there are apparently FHE schemes that can compute enc(km) from enc(m) and k much more efficiently than Paillier encryption, within a circuit.

Exploration of using FHE to perform this known-scalar multiplication are left to the reader. We’ll treat known-scalar multiplication as a blackbox that we know can be achieved (albeit possibly inefficiently within a circuit).

Setup

Choose two large primes p and q, such that gcd(pq, (p-1)(q-1)) = 1. This property is apparently assured if both primes are of equal length. Assume they’re of equal length, because we can use the following more-efficient approach.

Compute:

n = pq

\lambda = \phi(n) = (p - 1)(q - 1)

\mu = \phi(n)^{-1} \mod n

(Note: \phi(n) := (p - 1)(q - 1))

Let g := n + 1.

- Public key: (n, g)

- Private key: (\lambda, \mu) (or just \lambda would suffice).

Encrypt

Let m be the message to encrypt, where 0 \leq m < n.

Select random r where 0 < r < n and gcd(r, n) = 1.

Compute ciphertext c = g^m \cdot r^n \mod n^2. So c \in \mathbb{Z}^*_{n^2}.

Decrypt

Compute message m = L(c^\lambda \mod n^2) \cdot \mu \mod n,

where the function L is defined as L(x) = \frac{x - 1}{n}.

See the next next next section for why this works.

Multiplying a ciphertext by a known scalar

We can take a ciphertext enc(m) and known scalar k and compute enc(km) (without knowledge of m) by computing:

enc(km) = enc(m)^k

This works because:

enc(m)^k = (g^m \cdot r^n)^k \mod n^2 = (g^{km} \cdot (r^k)^n) \mod n^2

And if you view (r^k) simply as some different randomness – and observing that the earlier criterion of gcd(r, n) = 1 still holds for gcd(r^k, n) = 1 – then raising to the power does indeed leave us with a new paillier ciphertext that is the encryption of km.

Computing that exponentiation on a very large number (~2048 bits) will be painfully expensive inside a snark, but you’re having fun so who cares.

Why does decryption work?

Why is it true that m = L(c^\lambda \mod n^2) \cdot \mu \mod n?

Expanding c:

m = L((g^m \cdot r^n)^\lambda \mod n^2) \cdot \mu \mod n

m = L(g^{\lambda m} \cdot r^{\lambda n} \mod n^2) \cdot \mu \mod n

Big observation: r^{n\lambda} \equiv 1 \pmod{n^2}. Why?

By the definition of \lambda, it is the Carmichael function \lambda(n) wrt n.

So, for any integer x coprime to n,

x^{\lambda} ≡ 1 \mod n

r is coprime to n by definition. So:

r^{\lambda} \equiv 1 \mod n

So there exists some integer k such that:

r^{\lambda} = 1 + k n

Raise both sides to the n-th power:

(r^{\lambda})^n = (1 + k n)^n

Using the binomial theorem:

(1 + k n)^n = 1 + n(k n) + \frac{n(n-1)}{2}(k n)^2 + \cdots

All terms after the first two contain at least a factor of n^2.

Therefore:

(1 + k n)^n \equiv 1 + k n^2 \equiv 1 \pmod{n^2}

And so

(r^{\lambda})^n \equiv 1 \pmod{n^2}

Great! So we can cancel (r^{\lambda})^n from our earlier equation:

m = L(g^{\lambda m} \cdot r^{\lambda n} \mod n^2) \cdot \mu \mod n

m = L(g^{\lambda m} \mod n^2) \cdot \mu \mod n

Since g := 1 + n, then by binomial expansion:

g^{\lambda m} = (1 + n)^{\lambda m} \equiv 1 + m \lambda n \mod n^2

So:

m = L(1 + m \lambda n \mod n^2) \cdot \mu \mod n

Since L(x) = \frac{x - 1}{n}, we have:

m = \frac{m \lambda n \mod n^2}{n} \mu \mod n

Reasoning about that “mod n^2” term, we have that for some k (different from earlier k's):

m = \frac{m \lambda n + k n^2}{n} \mu \mod n

m = (m \lambda + k n) \mu \mod n

m = m \lambda \mu \mod n

And since \mu := \lambda^{-1} \mod n, we finally reach m!

Disclaimer

This post is provided solely for informational, academic, and exploratory research purposes. Nothing herein constitutes legal, financial, investment, or security advice, nor any other form of professional counsel. The concepts described are experimental and may be incomplete, incorrect, insecure, or subject to significant technical or theoretical limitations.

The content is provided on an “as-is” basis without any representations or warranties, express or implied, regarding accuracy, completeness, reliability, or fitness for any purpose. Any protocols, constructions, or implementations discussed may involve substantial legal, regulatory, compliance, or security risks, and readers should conduct their own independent analysis before relying on or applying any part of this material.

The author expressly disclaims all liability for any direct or indirect loss, damage, or consequences arising from the use, misuse, interpretation, or implementation of the ideas presented herein.