What if we only kept 1 year of active state?

Special thanks to Gary Rong, Gabriel Rocheleau and Guillaume Ballet for reviewing this article.

We’ve talked a lot about state expiry as a long-term fix for Ethereum state growth, but there’s been little data on how it would affect day-to-day node operation.

To make the discussion more concrete, we ran a simple experiment using real mainnet workload: execute ~1 year of blocks on (1) a node with the full state and (2) a node that keeps only 1 year of active state (based on what’s actually touched during block execution).

Disclaimer: this is not a full protocol implementation of state expiry (no revive witnesses, no network retrieval). It’s a “what-if” performance experiment: what happens to execution performance if the DB only contains the state you actually touch over the period?

TL;DR

- State size dropped by ~78%.

- Block re-execution time improved ~15% over the same ~1 year of mainnet blocks.

- Read performance accounts for most gains, especially storage reads (P50 -46%, P99 -36%).

- Tail latency improves, which matters for staying near head under load (P99 block insert -21%)

Benchmark Setup

In this experiment, we compare a node with the full state vs a node that only stores 1-year worth of active state.

- Client: go-ethereum v1.16.5

- Machine: follows the spec in EIP-7870

- Workload: execute blocks from 19,999,256 to 22,627,956 (~1 year)

- Runs: 3 times, report the average

How the 1-year active state DB was built:

- Sync a node from block 19,999,256 → 22,627,956 (the “tracking” node).

- Every time a piece of state (accounts, storage slots, trie nodes) is accessed during block processing, mark it as touched.

- Start from a DB at block 19,999,256, then delete unmarked state using the markings from the tracking node. This becomes the pruned DB.

- The pruned DB is not compacted manually after deleting state.

Note: Failed txs still trigger marking (because they still touch state during execution attempts). In actual expiry implementations, markings may not be considered for failed txs, which increases the set of inactive state.

Results

1. State size

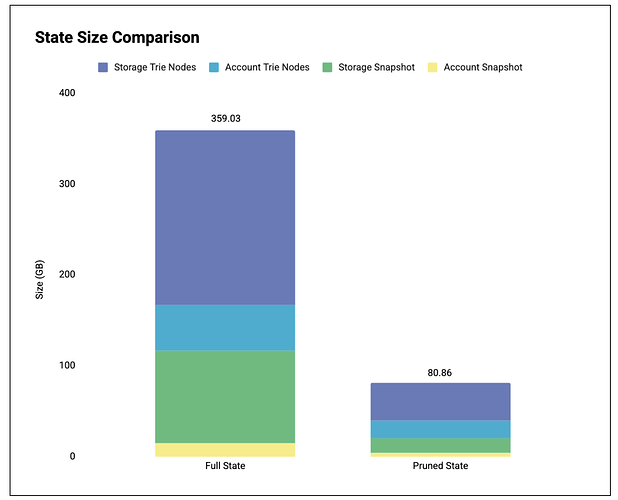

Figure 1: State size comparison in the DB.

Table breakdown (in GB):

| Full State | Pruned State | Reduction | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Account Snapshot | 14.65 | 3.60 | 75.43% |

| Account Trie Nodes | 50.34 | 19.89 | 60.49% |

| Storage Snapshot | 101.87 | 15.95 | 84.34% |

| Storage Trie Nodes | 192.17 | 41.42 | 78.45% |

| Total | 359.03 | 80.86 | 77.48% |

Result: large disk footprint reduction.

- Full state: 359.03 GB

- Pruned state: 80.86 GB (-77.5%)

Most of the footprint reduction comes from storage trie nodes. This reflects the fact that storage is much larger than the account trie to begin with, so there’s more to prune. The account trie, being smaller, has a higher access density: each account access keeps a larger fraction of the trie alive. The results are also aligned with our previous state analysis.

What is “snapshot” in geth?

In geth, snapshots are flattened representation of trie leaves (accounts and storage) to accelerate reads without walking trie paths. They are primarily a read-optimization structure.

2. End-to-end execution time

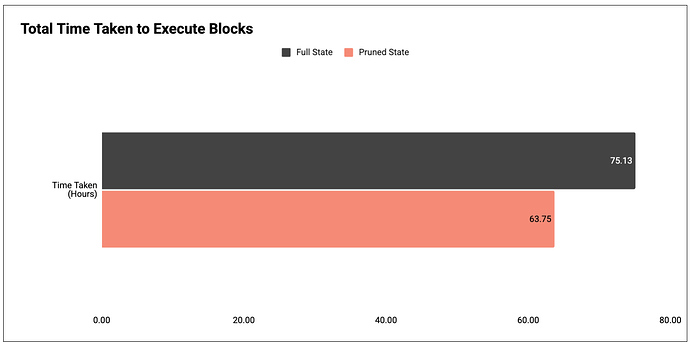

Figure 2: Total time taken to execute blocks 19,999,256 to 22,627,956.

Result: the pruned node finishes ~15% faster than the unpruned one.

- Full state: 75.13 hours

- Pruned state: 63.75 hours (-15%)

3. Block insert and prefetch

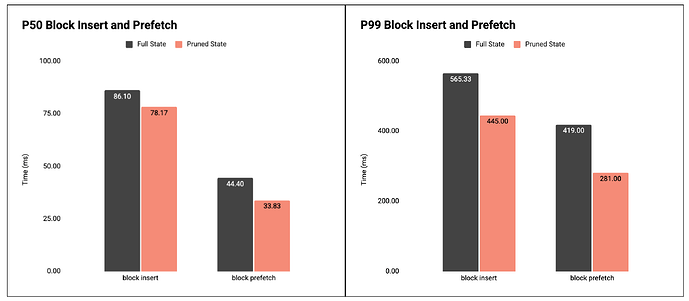

Figure 3: P50 and P99 time for block insert and block prefetch.

Result: both block insert and prefetch are faster with the pruned DB, especially at P99.

- Block insert (execution path):

- P50: 86.10ms → 78.17ms (-9%)

- P99: 565.33ms → 445.00ms (-21%)

- Block prefetch:

- P50: 44.40ms → 33.83ms (-24%)

- P99: 419.00ms → 281.00ms (-33%)

What is “prefetch” in geth?

Geth runs a parallel prefetcher that executes transactions to learn which state will be needed, pulls those objects into memory, and then discards the changes. The goal is to warm caches so that the actual execution (including state root computation) hits memory more often and does less disk IO.

In practice, prefetch performance is particularly important in geth. The prefetcher executes transactions concurrently and frequently needs to resolve state from the underlying database, which resembles the access pattern we expect from block-level access lists (BALs). In contrast, during block execution, the expectation is that most state accesses hit cache, making marginal improvements harder to observe.

Overall, the improvements in prefetching highlight the benefits of removing inactive state from the database.

4. State reads and updates

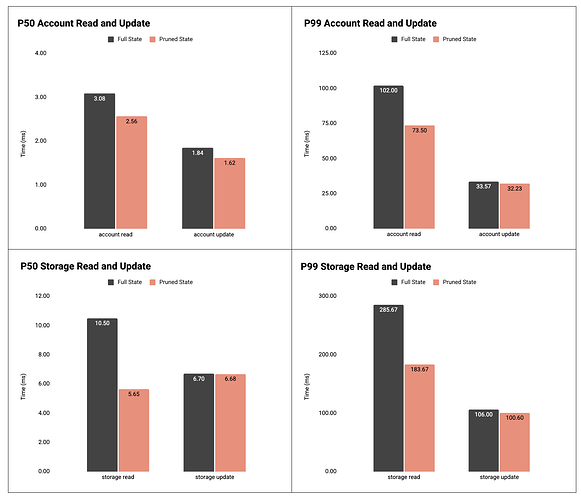

Figure 4: P50 and P99 time to read/update accounts and storage slots.

Result: account and storage reads improve significantly.

- Account read:

- P50: 3.08ms → 2.56ms (-17%)

- P99: 102.00ms → 73.50ms (-28%)

- Account update:

- P50: 1.84ms → 1.62ms (-12%)

- P99: 33.57ms → 32.23ms (-4%)

- Storage read:

- P50: 10.50ms → 5.65ms (-46%)

- P99: 285.67ms → 183.67ms (-36%)

- Storage update:

- P50: 6.70ms → 6.68ms (~flat)

- P99: 106.00ms → 100.60ms (-5%)

This lines up with the block insert/prefetch results. Updates show limited improvement because geth already prefetches the required trie nodes during transaction execution and blocks until prefetching completes. As a result, trie updates are performed entirely in memory, simply placing state changes into the appropriate positions in the trie.

Key Findings and Implications

- State size reduces drastically

The pruned state is about 4.4× smaller, shrinking from 359 GB to 81 GB. This kind of reduction materially lowers the storage and IO burden on node operators, and pushes the “reasonable hardware” line in a more accessible direction.

The reduction is concentrated in storage trie nodes and storage snapshots, which suggests that much of Ethereum’s state is cold contract storage. If most of the savings come from storage, then one potential path for state expiry is to focus solutions that prioritize expiring contract storage. This path leaves accounts untouched which avoids some of the more visible UX risks (for example, accounts unexpectedly requiring revival), while capturing a large fraction of the expiry benefits. The downside is that we may steer users to use accounts as a form of contract storage to avoid expiry, which we may end up doing both account and slot-level expiry.

- Reduced state size = faster execution.

Shrinking the state improves block processing primarily by reducing the cost of retrieving state from disk. Over the same year of mainnet blocks, end-to-end execution time improves by about 15%. The micro-metrics are consistent with this: the largest wins show up on reads, especially storage reads.

This matches what you would expect from LSM-based databases: a smaller dataset tends to improve locality. Practically, this creates headroom in two directions. We can raise gas limits, and we can make state operations less expensive if the state size is under control.

- Improves tail latency

Beyond average speedups, the more operationally important result is the improvement in tail behavior. The pruned database reduces P99 latency for block insert and prefetch substantially, which means fewer long stalls during validation. Those stalls are often what cause nodes to intermittently fall behind the head of the chain under bursty workloads.

What it means for state growth?

Our experiment suggests that if Ethereum could safely limit locally stored state to a rolling window of recently accessed data, clients would benefit from:

- Lower hardware requirements.

- More headroom for higher throughput, since state operations are a major bottleneck currently.

- Better resilience under load, due to improved tail latency.

However, the missing piece is the actual state expiry implementation. Whether it’s in-protocol or out-of-protocol, there will be additional latencies due to the need to mark, delete and revive expired state. Our experiment here using mainnet workload shows positive result, but these trade-offs need to be evaluated end-to-end for any concrete expiry proposal.

Future Work

- Measure how pruning inactive state helps (or fails) in worst-case patterns.

- Repeat the benchmark across other EL clients and compare the findings.

- Explore variants of expiry rules (e.g. 6-months expiry period, prune contract storage only, prune accounts only) and see how the benchmark results differ.