Thanks to Gustavo Gonzalez (Taiko), Jason Vranek (Fabric) and Lin Oshitani (Nethermind) for their review and feedback.

Overview

I’d like to describe a mechanism to extend the flexibility of rollups. I learned the core insight through Taiko’s anchor transaction mechanism and Nethermind’s Same Slot L1->L2 Message Passing design, and I would generalise it to the statement:

L2 users and contracts can rely on arbitrary assertions about future state, provided their transactions are conditioned on those assertions eventually being proven.

This article will unpack that statement and provide some example use cases. We will cover:

- Background information about rollup communication, focussing on timing.

- Anchor blocks for reading L1 state.

- Same-slot message passing.

- A mechanism for realtime L1 reads.

- A mechanism for interdependent L2 transactions.

- Mechanisms for cross-rollup assertions.

- A suggested implementation framework.

- An example walkthrough.

To forestall a possible misunderstanding, it’s worth emphasising that my preference is for protocols to strictly define and enforce simple, secure and flexible abstractions. For convenience (or as a Schelling point), the developer team may enshrine some particular use cases, but they should always be implemented at a higher layer. Therefore, this article attempts to improve flexibility in two directions:

- the mechanism (explained below) is generalised to allow arbitrarily complex assertions.

- the sample implementation exposes the “assertion” primitive to users, developers and sequencers, allowing them to build whatever systems they choose with whatever risks they accept. The protocol’s job is to provide the framework and ensure risks are contained, so they only affect participants who choose to opt in.

Background

Every 12 seconds, Ethereum selects an L1 proposer that can aggregate new L1 transactions into a block and add it to the chain.

L2 transactions are derived from data published in an L1 transaction. Typically, they are aggregated into L2 blocks with a shorter block time, so there are several L2 blocks per L1 block.

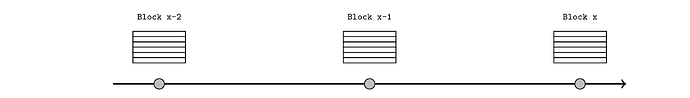

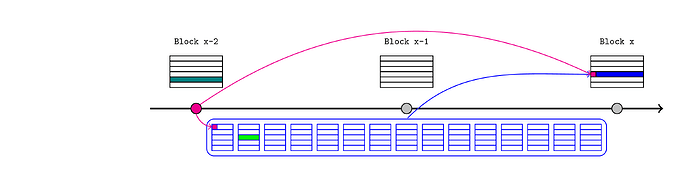

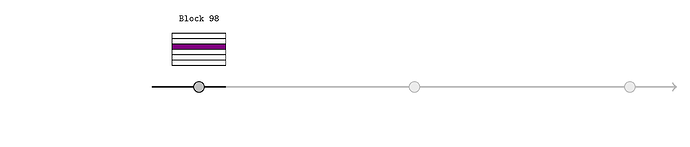

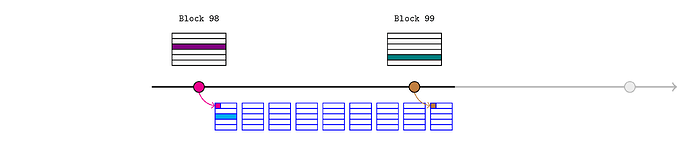

We are focussed on potential functionality that can be offered by an L2 sequencer with monopoly rights until a particular slot, typically spanning several L1 blocks (although just two are depicted here).

Such a sequencer would be partially limited in their flexibility to reorganise L2 transactions over several slots, because they may offer preconfirmations or liveness guarantees to users. Whenever we discuss a transaction occurring on L2 before it is actually published to L1, we really just mean that it can influence later transactions and the sequencer is unlikely to remove or delay it. For simplicity, this article will default to describing L2 blocks as if they are continuously created and finalised in real time.

Anchor blocks

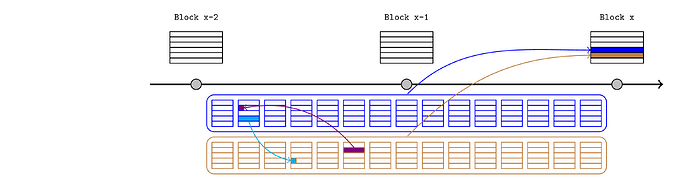

We need a mechanism to send messages from L1 to L2, so that L2 users and contracts can react to L1 activity. I will describe Taiko’s standard architecture, although the concepts are broadly applicable across rollups.

The L2 sequencer is required to start each block with an anchor transaction, and pass in a recent L1 block number and state root as arguments. Any user can then prove that a particular storage value is consistent with the latest state root, and the rest of the chain can proceed with this knowledge.

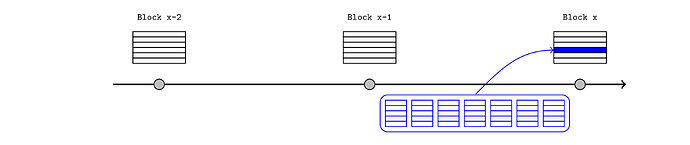

For example, consider a scenario spanning a cross-chain token deposit and a few subsequent L2 blocks:

- an L1 bridge contract receives the tokens and records this fact in L1 storage (the dark green transaction in the below diagram).

- the L2 sequencer passes the latest L1 state root (pink) to the anchor transaction at the start of an L2 block.

- the token recipient (or anyone else) provides a Merkle proof to an L2 bridge contract demonstrating that the deposit was saved under the relevant storage root within the L1 state root. This convinces the L2 bridge that the deposit occurred on L1, so it releases or mints the L2 tokens (light green).

- those tokens are now immediately available to interact with the rest of the L2 ecosystem in future transactions and blocks.

Note that at this point the sequencer has directly asserted the L1 state without justification. Although it is public information (in the sense that anyone can retrieve the value from an L1 node), this cannot be validated from inside the L2 EVM so L2 contracts must simply trust that it was correct. A sequencer that passes an invalid state root could fabricate a plausible alternate history that would be self-consistent from within the L2 EVM. This is eventually resolved when the bundle is published to the L1 inbox contract, which queries the relevant block hash so it can be compared to the injected state root.

Security architecture

Let’s review the security architecture implied by this mechanism. Constraints on L2 sequencers can be categorised as either:

- rules of the rollup, enforced by the L2 nodes and validity proofs.

- other commitments (such as preconfirmations), enforced by economic stake and reputation.

The anchor block requirement (and other assertions described in this article) fall into the first category. This means that all relevant information needs to be available on L1, and it also needs to be verifiable from within the L1 EVM when using ZK or TEE proofs. This is achieved by some combination of:

- performing relevant validations in the L1 Inbox contract at publication time.

- saving a hash of the available information at publication time, so it can be use to constrain the inputs to an off-chain proof.

In this case, the complete procedure is:

- the sequencer reads the latest L1 state and block number from their node.

- the sequencer passes these values to the anchor transactions, which saves them in the L2 state.

- in the Taiko case there is an anchor transaction per L2 block but only ones that update the latest L1 state are relevant for this article.

- the sequencer continues to build L2 blocks, and possibly preconfirms them.

- eventually the sequencer submits the whole bundle to the L1 Inbox contract.

- the Inbox contract calls

blockhash(anchorBlockNumber)and saves (a hash of) it along with the publication. - the rollup’s state transition function, implemented by the rollup nodes, validates the consistency of the entire bundle, which includes confirming (among many other things) that:

- the anchor transaction is called exactly once at the start of every block.

- the block number and state root arguments are consistent with the block hash queried by the L1 inbox.

In this way, a sequencer that asserts the wrong state root would invalidate the whole publication, just like they would if they violated any other state-transition rules like exceeding the block gas limit. Any L2 transaction that reacted to the invalid root (by minting tokens that did not have a matching L1 deposit, for instance) would be contained inside an invalid publication, so it would not be included in the final transaction history.

As we have seen, the sequencer’s claim when constructing the anchor transaction is not strictly “this is the state root of the latest L1 block” but rather “this state root is consistent with the block hash that will be retrieved in the publication block”. This describes a general pattern that we can use whenever:

- the sequencer knows something that they want to assert inside the L2 EVM, so that L2 users and contracts can build on it.

- any L1 information needed to prove the claim will eventually be available in the L1 EVM at publication time. Note that this does not mean the claim itself needs to be verified on L1, just that the final publication can contain a mixture of sequencer-provided data and L1-validated data.

- the rollup’s state transition function requires the claim to be proven for the publication to be valid.

My recommended assertion mechanism just instantiates this pattern generically.

Same Slot Message Passing

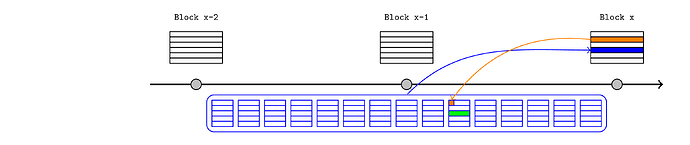

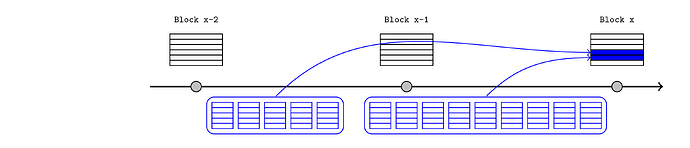

This idea was introduced by Nethermind and as explained in that post, it can be combined with their fast-withdrawal mechanism to perform a same-slot round-trip operation. Here I will just focus on the assert-and-prove structure of the L1-to-L2 message.

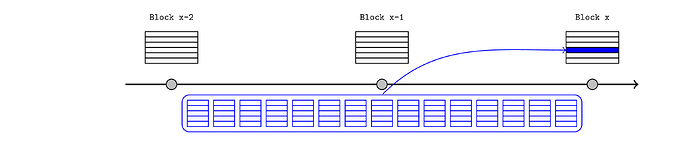

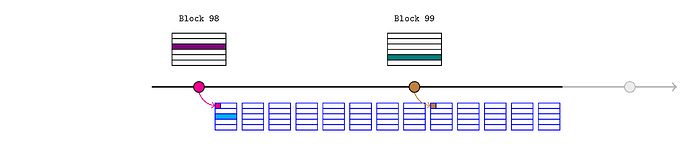

As noted, the anchor block mechanism requires the Inbox contract to query the block hash of the relevant L1 block, which implies it does not support reacting to transactions included in the current L1 block. However, an L2 sequencer that can predict that a particular L1 transaction will be included in the publication block (orange in this example) can assert that claim immediately in the L2.

For a same-slot deposit, the procedure would be:

- a user signs a transaction that deposits to an L1 bridge contract.

- the L2 sequencer believes this transaction will be included before their own publication transaction and it will succeed.

- typically this implies the L2 sequencer is also the L1 sequencer (i.e. it is a based rollup) but it could also be achieved with L1 preconfirmations.

- the sequencer constructs the corresponding “signal” (a hash of the deposit details) and passes it to the anchor transaction, which saves it in the L2 state. This should be interpreted as an assertion from the sequencer that the deposit will occur on L1.

- this convinces the L2 bridge, so it releases or mints the L2 tokens.

- the sequencer continues to build L2 blocks, and possibly preconfirms them.

- eventually the sequencer submits the whole bundle to the L1 Inbox contract.

- the Inbox contract executes an “existence query” to confirm that the signal was recorded in L1 storage. It also saves (a hash of) the signal along with the publication.

- the rollup’s state transition function, implemented by the rollup nodes, validates the consistency of the entire bundle, which includes confirming (among many other things) that the signal injected in the anchor transaction matches the one validated by the Inbox contract.

As before, this ensures that the sequencer’s assertion is confirmed at publication time, or the entire bundle is invalid.

Generalisation preview

This structure allows for some pretty direct generalisations. In particular, the Taiko Inbox contract is not actually interacting with the same-slot L1 transaction at all, but merely confirms the existence of the signal it would produce in a dedicated SignalService contract. The Inbox could also look for evidence of any other L1 transaction (eg. oracle updates, airdrops, DAO votes, etc) that leave remnants in publicly accessible L1 storage. The mechanism works directly as long as the sequencer knows that:

- the L1 transaction will be included before their own publication, and

- nothing can happen in the mean time to invalidate it. In most cases, this requires the previous L1 block to have been already published.

It’s also possible to make the target L1 call directly from the L1 Inbox, which removes the need to update storage, but the proposer would need to cover the gas costs.

More interestingly, instead of simply insisting the signal exists, the Inbox could save (a hash of) whatever a set of arbitrary queries happen to return. In this way, the Inbox would be responsible for taking L1 actions and retrieving L1 state but would not need to know about the L2 assertions, or evaluate whether they were confirmed. This could be deferred to more complex L2 logic. For example, the sequencer could assert that a transaction will not happen on L1, or it could assert that a DAO proposal will have at least X votes at publication time, before knowing exactly how many votes it will have.

This should be clearer when we discuss my suggested implementation.

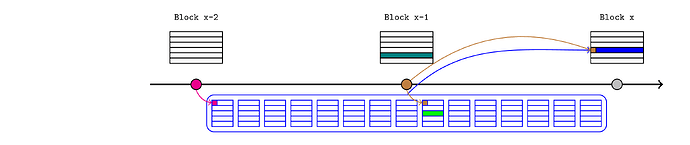

Realtime L1 reads

When an L2 publication spans several L1 slots, it will be useful if every intermediate L1 state root is asserted in the L2 state as soon as it’s known, which would allow the L2 contracts to respond to L1 updates as they occur. For example, the dark green transaction could be an update to an ENS resolver, or a new price in a price feed. The light green transaction could be a DeFi protocol that responds to that change immediately (as soon as the state is asserted), even though it occurred in the middle of a publication. This could be achieved straightforwardly by applying the anchor mechanism to every block.

Naively this appears to require the Inbox to make a different blockhash call for each intermediate block, but as an optimisation, the sequencer could reproduce the entire chain of L1 block headers on L2 (starting from the last validated one) when proving the assertions. If the last block hash is validated on L1, this implicitly validates the entire chain.

It’s worth noting that this mechanism allows the sequencer to provide realtime updates, but it does not compel them to do so. The rollup can be designed to enforce rules like “the L1 block hash needs to be asserted before any L2 transaction with a later timestamp”, but that is a statement about the final order that is recorded (which is under the sequencer’s control), not when it happened in realworld time. We would still rely on preconfirmations or other external mechanisms to constrain how long a sequencer can delay providing the latest block header.

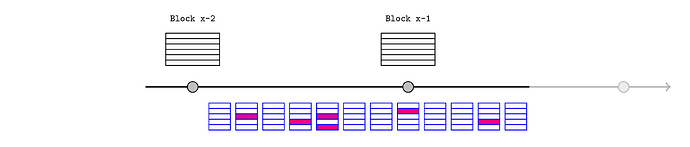

Interdependent L2 transactions

One category of state that the sequencer can predict is the L2 state within the publication that they are constructing. Having decided to respect some constraint about future state, they can assert that claim immediately so L2 contracts can rely on it.

This could simplify interdependent transactions. For example, consider a literal Prisoner’s Dilemma contract.

contract PrisonersDilemma is IPrisonersDilemma {

const uint256 COOPERATE = 1;

const uint256 DEFECT = 2;

mapping(address participant => uint256 choice) public choices;

function choose(uint256 choice) public {

require(choices[msg.sender] == 0);

choices[msg.sender] = choice;

}

function payout() public {

// partition rewards according to the Prisoner's dilemma payout table

}

}

This example is typically used to explain game theory but in the context of blockchains, it is just a coordination and timing problem. The challenge is that whoever chooses second can freely select DEFECT without worrying about retaliation, which means neither participant will choose first. Ideally, both participants would publish a transaction that says “If my partner chooses COOPERATE, then I choose COOPERATE”. This is a stand-in for generic multi-party simultaneous transactions (eg. “if you send me an NFT, I will send you ETH” or “if you donate to this charity, I will giving you a positive rating”).

The standard way to solve this is for both participants to delegate their voting rights to an external coordination contract. Note that a 7702-enhanced EOA is insufficient because it is not binding: delegating to code that selects COOPERATE will not convince your partner because you can always change the code later. This adds complexity because both participants need to validate that there are no loopholes in the coordination contract, and adds timing overhead to account for delegating the rights and recovering from the possibility of a non-responsive partner.

Using assertions, each participant can declare their conditional choice unilaterally by executing (either through a contract or 7702-enhanced EOA) the following snippet:

// retrieve my partner's choice recorded in the next block

// we could use the same block but using the next block helps to emphasise the concept

partnerChoice = getAssertedFutureState(

block.number + 1,

prisonersDilemma,

abi.encodeCall(IPrisonersDilemma.choices, partner)

)

require(partnerChoice == COOPERATE);

// now that I am convinced my partner will choose COOPERATE, I can as well.

prisonersDilemma.choose(COOPERATE);

Assume both participants (let’s call them Alice and Bob) create and publish such a transaction. The sequencer can recognise that both transactions can succeed together. They can then sequence the following transcript:

- assert that the

choicescall in the next block will returnCOOPERATEfor both participants with the following snippet:assertFutureState( block.number + 1, prisonersDilemma, abi.encodeCall(IPrisonersDilemma.choices, alice), COOPERATE ) assertFutureState( block.number + 1, prisonersDilemma, abi.encodeCall(IPrisonersDilemma.choices, bob), COOPERATE ) - include Alice’s transaction in the current block to set her choice to

COOPERATE. Recall that this would revert if the sequencer did not already assert that Bob will chooseCOOPERATE. - include Bob’s transaction to set his choice to

COOPERATEas well. - at this point the game is complete but the sequencer still needs to prove the two outstanding assertions (explained below).

This mechanism allows users to simply state their desired outcome, offloading the coordination and complexity to the block builders. It could be simplified further if the participants make the assertions themselves (possibly using the pauser mechanism described below) with the following snippet:

// directly assert that my partner will cooperate. This transaction will not be sequenced if the sequencer disagrees.

assertFutureState(

block.number + 1,

prisonersDilemma,

abi.encodeCall(IPrisonersDilemma.choices, partner), COOPERATE

)

// now that I am convinced my partner will choose COOPERATE, I can as well.

prisonersDilemma.choose(COOPERATE);

This allows Alice to pay directly for the assertion she wants rather than compensating the sequencer independendently, and removes the possibility that she would pay for a reverting transaction (if hers was sequenced in isolation).

The mechanism also allows complex transactions to progressively resolve over time. For example, consider a user who offers to withdraw funds from their DeFi investment and provide an unsecured loan to anyone as long as the funds are returned with some minimum interest payment, potentially shared with the builder to justify the effort. This is like offering a flash loan in the sense that no collateral is required and the loan must be repaid or it never occurred, but it could span several L1 slots (as long as it’s still within the sequencer’s publication window).

The offer transaction will sit in the L2 mempool until the sequencer knows that it can fulfill the condition (i.e. there is another transaction that accepts the loan and repays the full amount with interest). At this point, the sequencer can assert that the loan will be repaid and preconfirm the offer transaction. The rest of the ecosystem can build on the knowledge that that loan will be repaid, by emitting events or preemptively paying out dividends (from non-loaned funds).

However, the sequencer does not have to confirm the particular transaction that justified the assertion. Instead, they could wait to see how the rest of the ecosystem develops in case there is a more profitable sequence of transactions. This could involve L1 deposits or oracle updates that can be asserted in L2, or it could just be new transactions in the L2 mempool. Once the specific loan sequence is chosen, the sequencer can include (and possibly preconfirm) those transactions and then prove that the assertion was fulfilled.

Cross-rollup assertions

The same pattern can be extended to provide cross-rollup atomicity, with some additional dependencies or assumptions. Consider a swap where Alice sends 10 ETH to Bob (light blue) on rollup A, in exchange for Bob sending Alice 10 ETH (purple) on rollup B. The goal is to ensure neither transaction can be included without the other, which is achieved by requiring the sequencer to assert the existence of the other transaction into both rollups. Each transaction will revert if the relevant assertion has not been made.

The particular mechanism and the corresponding security properties depend on the underlying assumptions, so let’s explore some options.

Setting

In this article we assume that the cross-rollup mechanism is implemented by an entity with temporary monopoly sequencing rights for all relevant rollups up to a given L1 slot. This is a natural scenario when dealing with based rollups, where each sequencer can opt in to whichever rollups they choose to support. However, we do not assume any agreements between rollups to guarantee shared sequencing. We expect a dynamic process where different sequencers can freely opt in or out of different rollups, or could be banned or have insufficient stake for some but not all rollups.

To be clear, the two approaches are not mutually exclusive. Major rollups can still coordinate on a shared sequencer (like AggLayer) to get all the composability and liquidity advantages, while rollup users can take advantage of the mechanism described here for cross-domain communication with smaller rollups and appchains. However, the opportunistic context creates a very strong requirement that complicates composability: the state of a rollup must be entirely derivable in the rollup’s node from the information available on L1, even if it depends on activity occurring on another rollup.

To understand this requirement, consider how our desired atomic transactions would be included (focussing on one side for simplicity, but the other side is symmetrical):

- an opportunity arises when a particular entity can sequence transactions for both rollup A and rollup B.

- this sequencer includes both interdependent transactions in their publications. Alice’s transaction on rollup A should only succeed if Bob’s transaction succeeds on rollup B.

- once the bundles are published, anyone running nodes for both rollups can reconstruct the state of both rollups and can confirm that both transactions succeeded.

- however, the next rollup A sequencer may not be running a rollup B node or know anything about the rollup B state. If they are unable to determine whether Bob’s transaction succeeded on rollup B, they do not know whether Alice’s transaction should succeed on rollup A. The rollup B state will eventually be proven on L1, but until then the rollup A sequencer cannot determine the current state of rollup A so they cannot build on top of it and the rollup will stall. Even if rollup B offers preconfirmations, we cannot force a rollup A sequencer to rely on them.

- therefore, the information about whether Bob’s transaction succeeded must somehow be available on L1 as soon as the next sequencer starts building (i.e. as soon as the rollup A bundle is published).

Realtime proving

This problem is trivially solved when we have real time proving. Any sequencer that created a cross-rollup assertion would be required to include a proof of the publication’s correctness when it is posted. In this way, the validated final state of rollup B (available on L1) could be used to prove the cross-rollup assertion in rollup A, just like all other assertions in this article that are provable at publication time.

Unfortunately, realtime proving is currently only possible for simple app chains with trivial state-transition functions.

Staked claim

An intermediate mechanism would be to require all sequencers to post the final rollup state with each publication. This would be part of the rollup specification, so an incorrect state root would invalidate the whole publication. By default, sequencers would be incentivised to post the correct value to ensure they receive the publication fees, to retain any staked deposit, and to remain part of the rollup’s sequencer set.

Note that this would be useful in the shared sequencer (eg. AggLayer) approach as well, since the posted state would function like a strong preconfirmation. It would be stronger than a regular preconfirmation because it limits the rollup to only two possible states (either the posted state is valid or the state has not changed) and any penalties would be automatically executed when the proof is eventually resolved.

In our case, cross-rollup assertions could be proven against the claimed state, whether or not it is eventually proven correct. Using the cross-chain swap example (focussing on one side for simplicity, but the other side is symmetrical):

- the sequencer would decide to include both interdependent transactions.

- on rollup A, they assert that Bob will send 10 ETH to Alice on rollup B.

- Alice’s transaction on rollup A confirms the assertion and then executes the transfer.

- the sequencer continues to build L2 blocks on both rollups, and possibly preconfirms them.

- eventually both bundles are submitted to their respective Inbox contracts, along with the claimed state roots.

- the rollup A Inbox contract saves the claimed rollup B state root along with the rollup A publication.

- the rollup A’s state transition function validates the consistency of the entire bundle, which includes confirming (among many other things) that Bob’s transaction is recorded in the claimed rollup B state root (so the assertion is proven).

Note that there is an extra level of indirection, which introduces a new risk. All the assertions in the article are treated as validity conditions for the whole bundle, so L2 contracts can build on them, blindly assuming they are correct. If they are not proven, any dependent transactions are discarded (or will revert) anyway. However, in this case, the assertion is only that Bob’s transaction is recorded in the claimed rollup B state root. This assertion could be correct even if the claimed state root is eventually proven to be incorrect. In this scenario:

- Alice’s transaction would be included in rollup A, but the whole rollup B publication would be discarded (so Alice would end up sending a one-sided transfer).

- The sequencer would lose all transaction fees associated with the discarded rollup B publication, along with any deposited stake.

This mechanism should only be considered if a user believes the cost to the sequencer is large enough to deter defecting in this way, or the stakes are low enough. It could also be used in any situation where the user only wants to ensure the absence of a transaction on the other rollup (since either the claimed state is correct or the other rollup’s state is unchanged). However, the rollup protocol itself should not rely on a staked claim for enshrined operations (such as the native bridge) because this would spread the risk to users who had not opted in.

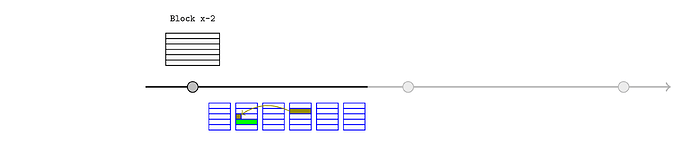

Sub-publication proving

Now that sub-slot proving has been demonstrated, we should consider designs where sequencers provide sub-publication proofs. We could imagine dividing the publication into blocks that come with a publication-time proof, and blocks that are yet to be proven. For simplicity, we could think of this as two different publications transactions (although they do not need to be).

It’s worth noting that proving any blocks in a publication implies ensuring the entire previous publication is already proven. In this case we could use the realtime proving mechanism, as long as the sequencer only makes cross-chain assertions about transactions in L2 blocks that they know they will be able to prove in time. Of course, blocks that consume or build on the assertion can still be proven after the publication.

Implementation Framework

As explained already, I believe rollup designs should support the general pattern of making assertions, but they should not be opinionated about which particular assertions are valid or how they should be resolved. Instead, individual sequencers should decide which assertions (if any) they support, and L2 users and contracts should decide which ones to rely on. This implicitly means L2 users are responsible for ensuring the proving mechanism chosen by the sequencer will reliably confirm the assertion.

The basic structure is a mapping (in an L2 contract) of unproven assertions that must be empty at the start and end of every publication. The assertionId is a hash of anything necessary to describe the assertion type as well as the msg.sender that created it, and it can only be cleared by the same address. The value would be any instance-specific data (or possibly a hash of it).

mapping(bytes32 assertionId => bytes32 value) public assertions;

Creating unproven assertions

For example, anyone could deploy a RealtimeL1State contract that asserts statements like “at L1 block B the state was S” and the assertion would map keccak256(abi.encode(address(realtimeL1State), B)) to S. The sequencer could invoke that contract whenever they want to update the L2 about the latest L1 state, creating a sequence of unproven assertions. The rollup will enforce (explained below) that these assertions are cleared by the end of the publication.

At this point, L2 users or contracts can see the assertions in the mapping, and can rely on them if they can be convinced that the RealtimeL1State contract will only clear the assertion if it’s proven to be consistent with the L1 history. They can use the asserted state to convince other contracts (that trust the RealtimeL1State contract) that a particular L1 contract had a particular value in storage.

Similarly, anyone could deploy a FutureL2Call contract that asserts statements like “at some point during L2 block B, calldata C invoked on destination D by this contract will succeed and return the value V” and the assertion would map keccak256(abi.encode(address(futureL2Call), B, C, D)) to keccak256(V). The sequencer could invoke that contract to guarantee that they will respect this condition, and L2 users or contracts can progress under this assumption.

Lastly, anyone could deploy a PublicationTimeCall contract that asserts statements like “calldata C invoked on destination D by the Inbox contract at publication time will succeed and return the value V”. They may want to allow generic conditions on the return value to cover cases where the sequencer knows the relevant property of V without knowing it exactly. Interestingly, this could include cases where the sequencer is guaranteeing statements about their own publication, such as “this L2 transaction will be included if the L1 DAO votes for it”. To allow for this flexibility, the assertion could be generalised to “calldata C invoked on destination D by the Inbox contract at publication time will succeed and return a value that can be passed to L2 function F (also at publication time) to return the value V”. The assertion would map keccak256(abi.encode(address(publicationTimeCall), C, D, F)) to keccak256(V). The intuition here is that the Inbox needs to perform the L1 calls and save (a hash of) the results, but user-defined L2 contracts can describe the assertion and evaluate whether it is proven. Note that this mechanism can be used to cover queries for publicly available state (eg. previous deposits in a bridge, oracle updates, DAO vote tallies), actual L1 state-changing actions (eg. depositting in a bridge, updating an oracle, voting in a DAO) or values describing other rollups (eg. the latest proven state or the state claimed by the sequencer).

As the publication is being built, it will contain a growing collection of assertions that need to be proven.

Proving assertions

Assertions that only rely on L2 state can be resolved within the publication. For example, the FutureL2State assertion (that “at some point during L2 block B, calldata C invoked on destination D by this contract will succeed and return the value V”) can be cleared in block B by making the call and ensuring it returns the correct value. The sequencer must ensure that such a transaction is included for the publication to be valid.

The ones that require L1 state would need assistance from the rollup state-transition-function (implemented by the rollup nodes). For example, if the RealtimeL1State contract was provided with the block hash of L1 block X:

- anyone could provide the entire L1 header to prove it has the expected hash.

- since the header includes the state root and the previous block hash, both of these values would be proven.

- this could be repeated with the hash of block X-1 to find the state root of block X-1 and the hash of block X-2.

- this could be repeated to cover all L1 state roots that occurred during the publication.

The question is how to ensure the provided hash for block X was accurate. My suggestion is to gather all the relevant L1 data in the Inbox contract, which should cover the latest L1 block hash and the result of all calls specified by the sequencer. The hash of this data (let’s call it the consistency hash) will be included as part of the publication. Then, each publication should include an end-of-publication transaction that:

- accepts the consistency hash

- passes it (and any relevant information) to the assertion contracts, which can clear the assertions after validating they have been fulfilled.

- reverts if any unproven assertions remain.

The state-transition-function will guarantee that:

- this is the final transaction in the publication.

- the input hash matches the value computed on L1.

- the transaction succeeds.

This ensures that each assertion is proven according to the standards of the contract that created it, potentially using publication-time L1 data.

Note that since the consistency hash (orange in the diagram) is included in the end-of-publication transaction, this mechanism assumes the sequencer will be able to predict its value before publishing the bundle, which implies one of the following:

- this is a based rollup

- the result of the queries cannot be changed between the time the sequencer creates the end-of-publication transaction and the time the publication is confirmed in L1 (which would be the most common situation).

- the sequencer has received the relevant L1 preconfirmations.

This mechanism creates a minor complication for the staked cross-rollup assertion option. In that scenario, the sequencer is required to publish the claimed state of the rollup after the publication. However, rollup B’s claimed state would be part of rollup A’s consistency hash, which means it would affect rollup A’s final state. A two-way cross-rollup assertion using this mechanism would introduce a circular dependency. This could be resolved by noting the end-of-publication transaction has a very specific and predictable impact on the final state (it clears unproven assertions), but for simplicity and to avoid complications associated with gas costs the mechanism could be altered to require the sequencer to provide the state immediately before the end-of-publication transaction.

Assigning roles

An interesting question to consider is who has the authority and incentive to make and prove assertions. As described, the sequencer is allowed to include an arbitrary list of L1 calls to make when publishing their bundle. The rollup node only enforces that a recent L1 block hash (chosen by the sequencer) and the result of these calls will be faithfully passed to the end-of-publication L2 transaction and that this transaction succeeds. The rest of the logic is contained within regular L2 contracts, which must be invoked with regular L2 transactions that pay L2 gas.

Since the sequencer is providing an additional service for users, they would likely charge for:

- any increased L1 gas costs that they incur (eg. to pay for additional queries in the Inbox)

- any L2 gas costs that they incur (eg. to make or prove an assertion)

- any opportunities they may lose from constraining their options when building publications.

- any effort it takes to validate whether they will be able to prove any assertions that the users want (eg. ensuring an L1 query will have a predictable result at publication time).

As a convenience, I recommend the assertion contract to be enabled and disabled by a pauser address that is set by anyone when it is zero and reset to zero in the end-of-publication transaction, which allows the sequencer to set a trusted pauser address at the start of the publication. This is not strictly necessary because the sequencer can also refuse to include transactions that make unendorsed assertions, but it provides a mechanism for the sequencer to coordinate with users and to defer the costs. In particular, the pauser address could be a contract that only allows assertions from a whitelisted set, and may require the user to provide enough upfront evidence and pay enough fees. For example:

- a user that claims the block hash for L1 block B is H could provide the L1 header that is needed for the proof, along with enough funds to cover the

blockhashquery on L1. - a user that wants an assertion that some property will be true in L2 block X could also sign the proof transaction that will need to be sequenced in block X.

The sequencer is still responsible for ensuring all assertions are proven (so they should only include transactions that make valid provable assertions) but this mechanism defers some of the analysis and cost to the user. It also allows users to create the assertion and react to that assertion within the same transaction, so they remove the risk of signing transactions that might revert if the assertion is not made beforehand. In some sense, this makes it possible for users to create transcript-level (rather than EVM-level) conditions on transactions, such that the transactions can only be included in the presence of other transactions.

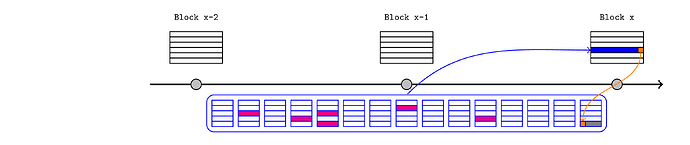

Example walkthrough

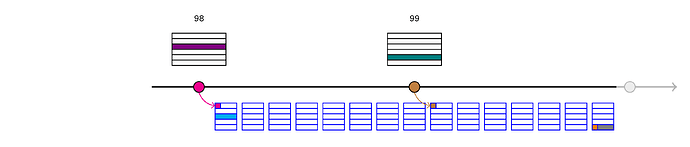

Let’s walkthrough a possible price-feed example in detail using the sample PreemptiveAssertions and RealtimeL1State contracts deployed on L2. This may be overkill if the publications are only a few L1 blocks long (since we’re only saving a few L1 blockhash calls) but this example is detailed enough to elucidate the mechanism.

Context

Assume there is a monopoly sequencer until L1 block 100, and the price feed has just updated (purple) in block 98. Of course, this mechanism can be naturally extended to cover several L1 blocks.

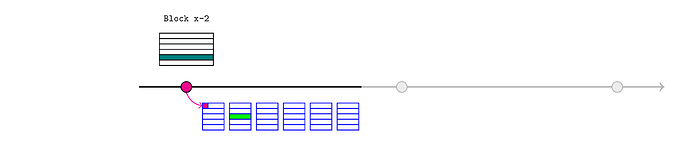

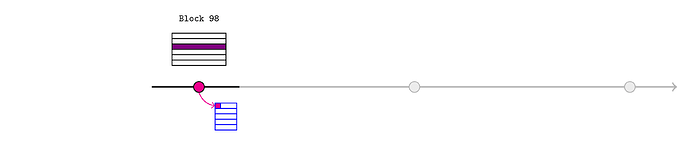

Step 1

Alice would like to inform an L2 oracle of that new price, so she retrieves the block header for L1 block 98 and calls

realtimeL1State.assertL1Header(98, header);

The sequencer should only include this transaction if it corresponds to the real header. They could also ensure that Alice pays a fee to cover the eventual blockhash(99) call on L1 (possibly using the pauser mechanism).

This creates three assertions:

- the blockhash of L1 block 98 is the hash of the provided

header - the parent hash of L1 block 98 is the

header.parentHashfield (unused in this example) - the state root of block 98 is the

header.stateRoot(pink in the diagram)

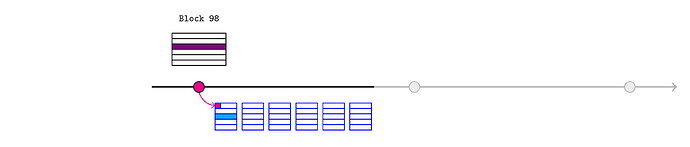

Step 2

We assume the L2 oracle trusts assertions made by the realtimeL1State contract (which actually implies the developers of the L2 oracle believe that the RealtimeL1State code correctly validates the assertion it makes). It should be designed to retrieve the latest L1 state root assertion when invoked.

Alice can provide a Merkle proof to the relevant storage location against the asserted state root to prove the latest price at the end of L1 block 98 (light blue).

The rest of the L2 ecosystem can proceed using this price.

Step 3

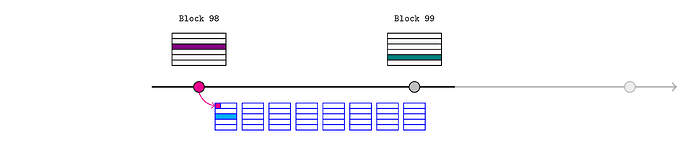

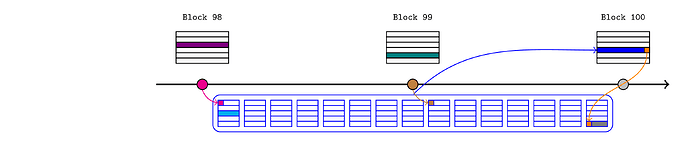

The price feed updates (dark green) in block 99.

Step 4

Bob would like to inform the L2 oracle of that new price, so he retrieves the block header for L1 block 99 and calls

realtimeL1State.assertL1Header(99, header);

As before, the sequencer should only include this transaction if it corresponds to the real header (and Bob has paid the required fees).

This creates three more assertions:

- the blockhash of L1 block 99 is the hash of the provided

header - the parent hash of L1 block 99 is the

header.parentHashfield - the state root of block 99 is the

header.stateRoot(brown in the diagram)

Step 5

As before, anyone can use the asserted state root to prove the latest price at the end of L1 block 99, and the rest of the L2 ecosystem will proceed using this price.

Step 6

Once the block 99 header has been asserted, the block 98 assertions are no longer necessary. At this point, anyone can remove them with the call

realtimeL1State.resolveUsingNextAssertion(98)

The sequencer could design their pauser contract to call this at the end of Step 4 (so Bob pays for it). Alternatively, they could require Alice to sign this transaction in Step 1 (but only sequence it now) so she pays for both adding and removing the assertions.

In either case, this call will

- confirm the asserted blockhash of L1 block 98 matches the asserted parent hash of block 99 (which guarantees the block 98 assertions are implied by the block 99 assertions)

- remove all three block 98 assertions.

Step 7

The end-of-publication transaction accepts the consistency hash (orange), which is derived from (among other things) the result of blockhash(99) executed in the Inbox contract at publication time (block 100). The sequencer can predict this value and pass it to the end-of-publication transaction while finalising the publication.

The sequencer will also specify that the realtimeL1State contract has unproven assertions, so the end-of-publication transaction will call resolve on that contract with the consistency hash (along with the block hash for L1 block 99 provided by the sequencer). This function will:

- confirm that the passed block hash corresponds to the consistency hash (so it matches the value that will be retrieved on L1).

- confirm that this matches the block hash that was asserted for block 99 (in Step 4).

- remove all three block 99 assertions.

The end-of-publication transaction will confirm that there are no remaining unproven assertions.

Step 8

Lastly, the sequencer finalises the publication and posts it in block 100. That state-transition-function (enforced by the rollup nodes) will guarantee that the consistency hash computed in the Inbox matches the one passed to the end-of-publication transaction and that it did not revert (to ensure all assertions were proven).