Thank you Jason Vranek, Ellie Davidson, Gal Rogozinski and Matheus Franco for reviewing

Ethereum’s scaling roadmap worked — maybe too well.

We now have dozens of rollups, appchains, and modular execution layers, each with its own sequencer, gas market, and state.

That’s great for scalability — but it’s fractured the network. Liquidity, apps, and users are trapped in silos.

The next frontier isn’t throughput — it’s reconnection.

Two major design philosophies are emerging to make Ethereum feel whole again:

-

Synchronous Composability (SC) — a protocol-level approach that extends Ethereum’s atomic execution model across rollups.

Messages between domains (chains) are passed instantly and atomically, so for developers and users, execution feels synchronous — like a single Ethereum transaction. -

Intents — a user-level approach that abstracts away execution.

Instead of specifying how to perform an action, users declare what outcome they want, and a network of off-chain solvers competes to make it happen — bridging, swapping, or routing value between chains for a fee.

Both aim to connect Ethereum’s fragmented landscape.

But they do so from opposite ends of the stack

We’ll compare these two approaches across several key dimensions — execution model, latency, expressiveness, and use cases — to understand not just how they work, but what kinds of experiences and trade-offs they create for developers and users. By breaking each down along these axes, we can see how synchronous composability and intents offer fundamentally different paths toward Ethereum-wide interoperability.

Execution Model

Execution Model

Synchronous Composability

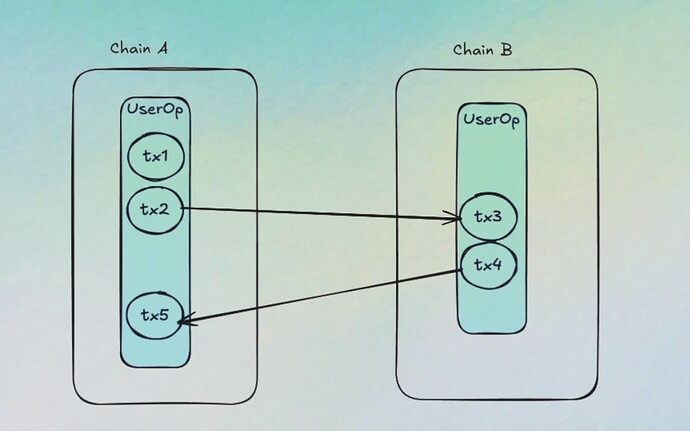

Synchronous composability lets messages pass between rollups in an atomic and instant way — every step succeeds together or reverts together.

That means I can flashloan on Rollup A, trade on Rollup B, and repay on Rollup A — all in one transaction.

There are a few ways to implement synchronous composability.

At its core, it requires a coordination layer that can order and execute cross-domain transactions atomically — ensuring that all involved rollups move forward in lockstep or revert together.

One common approach is mailbox-based message passing, a concept explored by Espresso.

Each rollup maintains a mailbox, a deterministic queue for pending cross-domain calls. The coordination layer then aggregates these mailboxes into a single, ordered execution bundle that spans multiple domains.

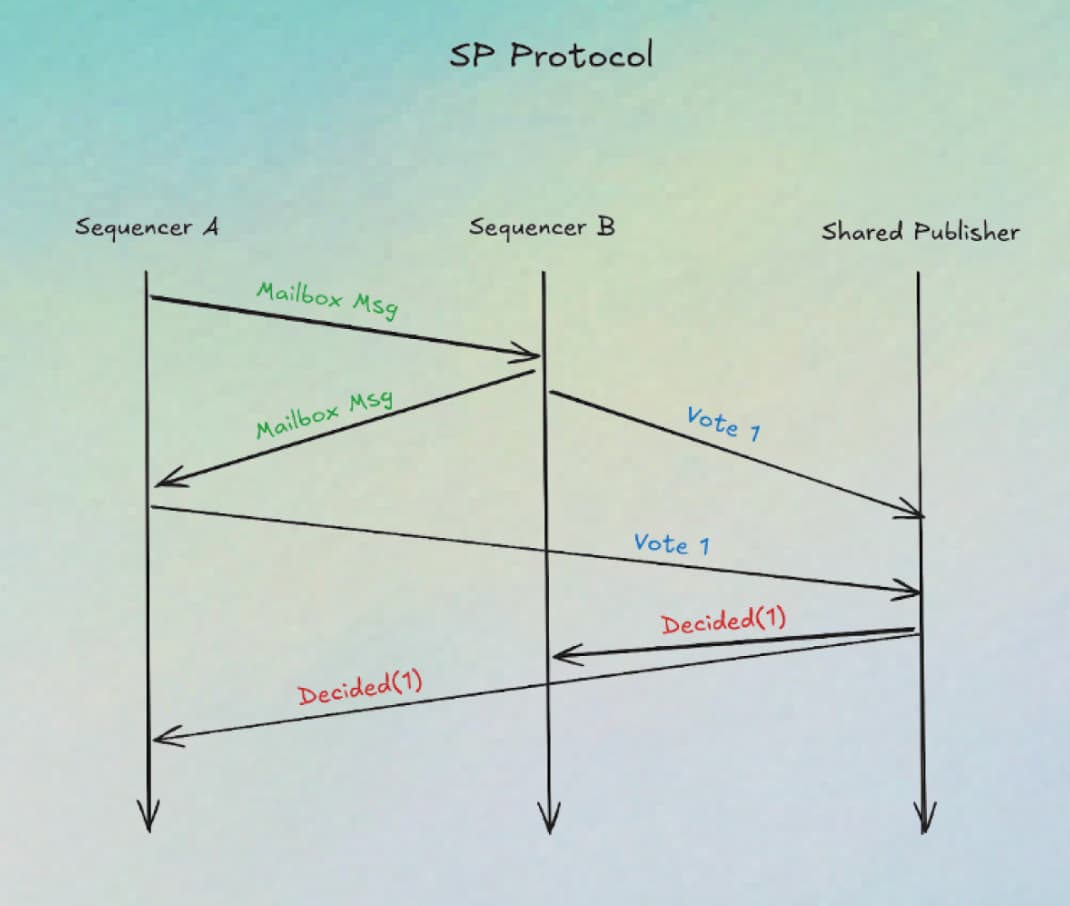

Compose.network implements this model using a Shared Publisher, which coordinates execution across rollups. Before committing, the Shared Publisher runs a simulation phase to verify that all cross-domain calls can succeed together. Only after the simulation passes does it finalize execution, enforcing the same ordered state transitions across every domain involved.

Another implementation path, proposed by Jason Vranek’s SCOPE protocol, achieves synchronous composability without mailboxes or a shared coordinator. It uses rolling hashes of cross-domain requests and responses to ensure every domain observes the same state transitions, and a super-builder model to bundle L1↔L2 transactions atomically. This design shows that synchrony can also be achieved through cryptographic equivalence proofs rather than centralized coordination.

The result is deterministic, atomic, and provable cross-rollup execution — making multi-chain apps feel like a single Ethereum transaction.

Intents

Intents invert the model.

Instead of defining how to perform an action, the user declares what outcome they want — for example:

“Bridge 100 USDC from Arbitrum to Base and receive at least 99.8 USDC.”

From there, a network of off-chain solvers competes to fulfill that goal. Each solver simulates potential routes — bridge → swap → transfer — and decides whether it can deliver the requested result profitably.Once a solver commits, it executes its own sequence of on-chain actions to fulfill the user’s intent.

For example, if a user wants to bridge 100 USDC from Arbitrum to Base and receive at least 99.8 USDC, the solver uses its own liquidity to send 99.8 USDC to the user on Base, then later claims the user’s 100 USDC locked on Arbitrum once the transfer is settled.

This flow happens off-chain from the solver’s perspective — it fronts the liquidity and only finalizes settlement on-chain once all steps complete successfully.

This execution is asynchronous in time but atomic in outcome — either the intent is fully filled or not filled at all. There’s no partial execution or stuck state.

The trade-off is that intents rely on solver profitability, not shared on-chain state. Solvers temporarily front liquidity and take on the risk of price movement, bridge delays, or reorgs. They’re compensated through solver fees or spreads built into the transaction.

Coordination happens through intent networks or frameworks like the Open Intents Framework (OIF) or CoW Swap, which standardize how intents are expressed, discovered, and settled.

-

Users broadcast intents (often signed off-chain).

-

Solvers compete to fill them through open auctions.

-

Winning fills are then settled on-chain via standardized contracts like ERC-7683.

This architecture shifts complexity away from on-chain execution toward off-chain coordination, optimizing for UX and liquidity depth. In theory, intents can be fully generic — able to describe any desired outcome — but in practice, their complexity grows rapidly with the number of domains and steps involved. Each intent type demands significant solver sophistication and capital, since solvers must front liquidity and manage execution risk across chains. While synchronous composability connects rollups through protocol-level determinism, intents rely on market-level competition constrained by these economic and operational limits.

Latency

Latency

This is one of the sharpest distinctions between the two models — the difference between synchronous finality and asynchronous coordination.

-

Synchronous Composability:

Execution is effectively instant.

Once a transaction is included in a block, all cross-domain logic finalizes atomically within that same block.

The coordination layer (or shared publisher, in Compose’s case) ensures that every domain involved transitions state together, so there’s no waiting for bridge confirmations or message relays.

From the user’s perspective, it feels exactly like a normal Ethereum transaction — no intermediate lockups and no pending fills.The only latency is block production itself. If the rollups share a common proof or sequencing window, state updates can even be verified within the same global slot.

-

Intents:

Intents, by contrast, are asynchronous by design.

Because solvers operate off-chain and front liquidity, they need at least one confirmed on-chain event — such as an asset lock — before acting.

This introduces a minimum one-block delay between the user’s broadcast and the solver’s execution.

In practice, solvers also wait for a few confirmations to guard against reorgs or invalid fills.Depending on network congestion, bridge latency, and solver liquidity, total completion time can range from a few seconds to tens of seconds.

Some frameworks optimize perceived speed — for example, showing users “instant fills” using solver-provided liquidity

The downside is non-determinism — users depend on market conditions and solver responsiveness, not consensus-level finality.

Expressiveness

Expressiveness

Synchronous composability is as expressive as Ethereum itself.

Because execution happens atomically across rollups, developers can compose arbitrary read/write operations between rollups just like they would between contracts on a single chain.

A cross-rollup transaction can include dozens of interdependent calls — flash loans, swaps, liquidations, or NFT transfers — all guaranteed to succeed or revert together.

This makes synchronous composability the foundation for multi-rollup dApps: protocols that span multiple domains but share one coherent state. Developers can write logic once, reason about it deterministically, and rely on the coordination layer (like Compose’s Shared Publisher) to synchronize execution across chains.

There’s no need for specialized middleware, liquidity provisioning, or off-chain routing — the network itself enforces atomicity and ordering.

Intents, on the other hand, are declarative and outcome-driven.

They express what a user wants, not how to get there.

That abstraction simplifies UX — the user only specifies the end goal — but it also limits programmability.

Each new type of intent (for example, “lend across two chains and hedge on a third”) requires new solver logic capable of interpreting, routing, and executing it safely and profitably.

In theory, intents can describe very complex operations; in practice, their expressiveness is bounded by solver sophistication and economic incentives. Solvers focus, mainly, on larger chains and tokens to maximize their profitability vs complexity function.

As intents grow more complex, the solver ecosystem must evolve — integrating price discovery, route simulation, and risk management across domains.

This pushes innovation off-chain, turning solvers into adaptive agents competing not just on price but on execution intelligence.

Defining outcomes in intents is not always as simple as it sounds. For straightforward use cases like a bridge or swap — “pay some token here, receive some token there” — the outcome can be clearly expressed and verified. But as soon as execution depends on dynamic, interdependent states, “defining the desired result” becomes a moving target.

How do you define the outcome of an arbitrage trade, where success depends on transient price spreads?

How do you encode a read operation that queries contract state on another chain mid-execution?

Or how do you define an intent that relies on runtime parameters — like oracle updates or auction results — that aren’t known upfront?

In those cases, writing an intent is like practicing test-driven development taken to its extreme: you must fully specify what “success” looks like before execution, but without full visibility into runtime conditions. It works for simple, well-bounded tasks — but quickly collapses when logic branches or depends on external state. Synchronous composability, by contrast, doesn’t require predefining success conditions at all — developers simply write executable logic that runs atomically across chains, with outcomes guaranteed by consensus rather than off-chain interpretation.

Use Cases

Use Cases

Synchronous Composability

Synchronous composability enables any use case that requires instant, atomic state transitions across domains — even when intermediate states depend on each other.

Because all operations finalize within the same global block, developers can safely compose complex, multi-rollup logic that would be impossible to express through asynchronous systems.

Typical use cases include:

-

Cross-chain no-liquidity bridging (direct state transfer)

-

Cross-chain swaps

-

Cross-chain flash loans

-

Multi-rollup atomic arbitrage and liquidation flows

-

NFT bridging

-

Complex DeFi strategies across multiple chains

-

Singleton dApps (deployed once for multiple chains)

Many of these — such as flash loans, cross-rollup liquidations, or multi-step arbitrage — cannot be replicated with intents, since they rely on synchronous guarantees and shared state visibility at execution time.

Intents can approximate them through liquidity-backed simulation, but they lack the atomic guarantees needed for deterministic multi-domain execution.

Intents

Intents excel at user-driven, goal-oriented operations — actions where the exact execution path doesn’t matter as long as the outcome is correct.

This makes them ideal for consumer-facing experiences and liquidity-driven coordination, such as:

-

Cross-chain swaps and bridges

-

Route optimization

-

Liquidity aggregation networks

-

L2->L1 bridging

However, intents are limited to asynchronous, result-based workflows. They cannot safely support logic that depends on immediate, verifiable state changes across domains within a single transaction — which is where synchronous composability truly shines.

One worth mentioning use-case is L2->L1 bridging, Intents excel in it without real competition from SC. At least until real-time ZK proving is widespread enough.

Summary

Ethereum’s scaling success came with fragmentation. Intents bridge that gap through off-chain coordination, but Synchronous Composability goes deeper — extending Ethereum’s atomic execution model across rollups.

By enabling instant, provable cross-domain transactions, it dissolves the boundaries between chains and unlocks experiences that feel like a single, global Ethereum. This new frontier in interoperability can redefine UX, liquidity, and adoption — turning Ethereum from a network of rollups into one synchronous economic system.