This post is a summary of discussions at a recent Robust Incentives Group meeting with input from all RIG members and Francesco.

Vertically sharding the mempool frees up bandwidth validators use for the execution layer mempool since validators would only need to download samples of blobs in the mempool instead of entire blobs. Lower bandwidth usage for the blob mempool is especially relevant as the number of blobs will increase by around 8x with PeerDAS, the next big upgrade planned to come to Ethereum around the end of 2025.

Only downloading samples of the data opens a DoS attack that needs to be solved. Dankrad proposed to use some form of prepayment to guarantee payment and limit the number of sybils that may flood the mempool. Francesco later proposed a specific form of sybil protection called mempool tickets.

The main two problem with the current mempool ticket proposals are:

-

Gas: the mechanism to allocate mempool tickets requires users to send transactions, distinct from their blob transactions, to buy mempool tickets. These transactions consume gas. The mechanism should not consume too much gas since that would gas left for regular users.

-

User Experience: the mechanism to allocate mempool tickets requires users to buy tickets in advance. This changes the user experience as users need to plan ahead how much demand they expect to have. How large the change to user experience is may be minimal in some designs (e.g. the Simple Mempool Tickets proposal below), but more pronounced in others (e.g. LIFO Mempool Leases). In the exceptional circumstance that a rollup must post a blob immediately and did not expect it, a rollup could always post through calldata.

It is especially hard to predict what a good user experience may feel like since current blob throughput is almost an order of magnitude smaller than what we expect to have in the short-term through PeerDAS and networking improvements. Both the throughput increase and mempool tickets would change user experience and it is hard to predict the effect of their interaction.

Mempool improvements are, however, very necessary. Therefore, in this post we:

-

Lay out 3 proposals for how mempool tickets may be implemented and explore their trade-offs.

-

Highlight that no hard fork is necessary to implement mempool tickets as the vertically sharded mempool is a networking upgrade that does not require a hard fork and the mempool tickets themselves can be implemented via a smart contract. The smart contract could relatively easily be changed in the future to accomodate changes in blob submitter behavior.

Wholesale Tickets

A wholesale ticket mechanism lets blob submitters buy a reasonably large amount of tickets at a time. In each slot k times as many tickets are sold as blobs are supplied, for example, we may sell 90 blob tickets even if only 9* blobs can be included in a slot at most (k = 10). Oversupplying tickets allows blob submitters to buy tickets for multiple slots at a time which may be operationally easier. Selling tickets in each slot ensures that rollups who need a ticket for the next slot can still buy it and prevents censorship that would occur if you sold in only one slot.

The mechanism works as follows:

-

Buying: Orders of the form

(sender_ID, number_of_tickets)are submitted to a smart contract during each slot. -

Allocation: The smart contract takes as input the orders and outputs a list of

sender_ID, their respectiveallocated_tickets, andticket_expiry_slot, which resembles when the tickets expire. For each order that interacts with the smart contract, it allocates \max(\text{number_of_tickets}, \text{tickets_left}), wheretickets_leftis a variable equal to the difference between the total number of tickets and the number of tickets already allocated. Allocation happens in each slot where there is at least one order. -

Blob Propagation: Ticket holders may propagate one blob per ticket they hold in any slot. Each node that participates in the vertically sharded mempool maintains a local list of how many tickets each

sender_IDhas left. After seeing samples of a unique blob, the node updates its local list by deducting 1 fromnumber_of_tickets.

Tickets expire since otherwise there could be a large reserve of tickets which would allow too many blobs to be propagated in the mempool at the same time which could create a DoS vector. The parameters to set here should be tested, however, there is a clear trade-off between the oversupply factor k and the validity duration that influences ticket_expiry_slot. If tickets are valid for a longer time, then we should sell fewer per slot in order to have the same maximum amount of valid tickets outstanding.

We do not propose refunds here for tickets, as was proposed previously, because refunding ticket costs requires a more costly system in terms of gas.

Mempool Leases

This mempool leases mechanism allows some ticket holders to keep their ticket over a longer time period while allowing anyone to buy a ticket in each slot. It does so by keeping a list of so-called lease holders. New lease holders may enter the set by either setting a deposit that is higher than the lowest deposit currently in the set, or by setting a minimum deposit and evicting the lease holder that was in the set for the shortest amount of time.

The mechanism works as follows:

-

Buying: Orders of the form

(sender_ID, number_of_leases, deposit_per_lease)are submitted to a smart contract in any slot. -

Allocation: We lay out two options for allocation. The first option is a stake-based system that is similar to a capped validator set used in some blockchains. The second option is a last-in-first-out system that aims to keep the lease holders in the set that are most likely to submit a blob soon again in order to minimize turn-over.

-

Stake Option: The smart contract maintains a list of length

Nthat contains lease holders as(sender_ID, deposit)for each lease holder. For each order that interacts with the smart contract and for each lease demanded (in the range ofnumber_of_leases), the contract checks whether thedeposit_per_leasein the order is larger than the lowestdeposita lease holder currently has deposited. -

Last-In-First-Out (LIFO) Option: The smart contract maintains a list of length

Nthat contains lease holders as(sender_ID, slot_entered)for each lease holder. For each order that interacts with the smart contract and for each lease demanded, ifdeposit_per_leaseis larger thanmin_deposit, the lease holder with the highestslot_enteredis removed from the set and the new lease holder’ssender_IDis added to the set along with the current slot number asslot_entered.

-

-

Blob Propagation: Each lease holder may propagate one blob per lease that they hold in the vertically sharded mempool.

If mempool leases were implemented today, we may see Base retain their lease for some consecutive slots. Other chains do not submit blobs as frequently (see the Blob Submitters table with “Past 24H ~🕰️ Between Blobs” in hildobby’s dashboard). The mempool leases mechanism may work better when the blob throughput per slot is a lot higher than it is today, for example, after an 8x increase in blob throughput PeerDAS may bring us around the end of 2025.

This mechanism may significantly impact blob submitter behaviour. Today, blob submitters tend to submit a large amount of blobs at the same time (e.g. 3 or 6 blobs per slot at a 9 blob limit throughput). Possibly, a mempool lease mechanism would make blob submitters submit blobs for which they still hold leases. If they hold 2 leases, they may submit 2 blobs over 3 slots instead of 6 blobs in one slot.

Moreover, the lease mechanism may benefit larger chains more than smaller chains. Smaller chains may not have the liquidity to deposit a lot of stake to gain a mempool lease in the stake-based system, which would prevent them from using the vertically sharded mempool. The LIFO system may favour larger chains since they will keep their leases without sending new order transactions. The advantage large chains obtain from this should be minimal since it just saves them some gas fees and is unlikely to influence competition between L2s in the bigger picture.

Simple Mempool Tickets

This proposal is the simplest mempool tickets proposal that uses a posted-price to sell an equal amount of mempool tickets as the maximum number of blobs that can be included in the block. This mechanism sells tickets in each slot.

The mechanism works as follows:

-

Buying: Orders of the form

(sender_ID, number_of_tickets)are submitted to the smart contract in any slot. -

Allocation (identical to Wholesale mechanism): The smart contract takes as input the orders and outputs a list of

sender_IDand their respectiveallocated_tickets. For each order that interacts with the smart contract, it allocates \max(\text{number_of_tickets}, \text{tickets_left}), wheretickets_leftis a variable equal to the difference between the total number of tickets and the number of tickets already allocated. -

Blob Propagation: Ticket holders may propagate one blob per ticket they hold.

The advantage of this proposal is that potentially no oversupply is necessary (k = 1) because tickets are bought in each slot. Therefore, there can be a hard cap on the amount of bandwidth nodes need for the blob mempool in each slot which increases the bandwidth nodes can use for other tasks.

This proposal is extremely similar to a previous proposal from Mike and Julian that used a first-price auction. We move to a posted-price mechanism here as it consumes less gas.

Loyalty Tickets

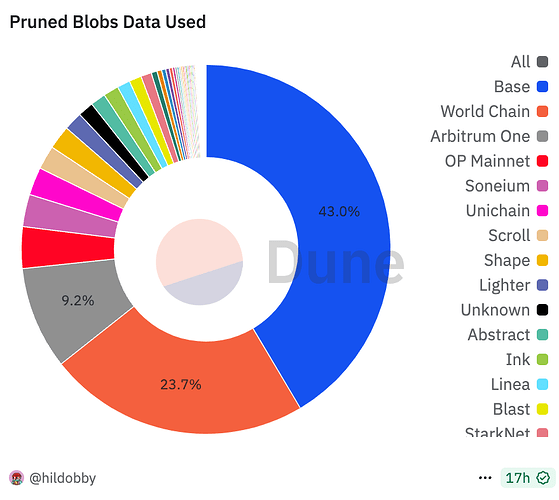

This proposal allocates tickets to those that have submitted blobs in the recent past. The goal is to supply mempool tickets to blob submitters who are most likely to submit a blob in the next slot. Figure 1 (taken from Hildobby’s Blob Dashboard) shows how Base consumes 43% of blobs, World Chain 24%, Arbitrum One 9% and the other rollups the remaining 24%.

Figure 1: Pie chart of blob usage showing a power law distribution.

The mechanism could work as follows:

-

Monitoring: In each slot, the smart contract takes as input which blob submitters (stored as

sender_ID) submitted blobs in the previous slot. The smart contract maintains weights for a set ofsender_IDs N. It assigns weights to eachsender_IDas follows:-

Update_{i} = \alpha \frac{Blobs_{i}}{Total \text{ }Blobs} + (1 - \alpha) Old \text{ } Weight_{i}

-

New \text{ } Weight_{i} = \frac{Update_{i}}{\sum_{i \in N} Update_{i}}

-

We may consider a minimum weight such that allocated blob submitters receive at least e.g. 3 tickets since blob submitters seem to submit at least 3 blobs per block to amortize costs.

-

-

Allocation: In each slot,

ntickets are allocated to the set ofsender_IDs N proportional to their weight, rounded to the closest integer and capped atmax_blobs.nmay be a multiple of the maximum amount of blobs that may be submitted in each slot. -

Blob Propagation: Ticket holders may propagate one blob per ticket they hold.

This mechanism looks similar to the LIFO Lease mechanism described above. Both try to allocate tickets to those that are most likely to need tickets in the next slot. I think simulation is necessary using current blob submitter behaviour to fully understand the differences between the two.

Moreover, Francesco proposed to mix this mechanism with the Simple Mempool Tickets mechanism to allow free entry while maximizing the probability that rollups who need tickets already have tickets.

Finally, the parameters would need finetuning to minimize the UX burden on rollups. We need simulation to do so. Since blob submitter behaviour is likely to change significantly as blob throughput increases, the parameters may need to be changed, which could be a change to the smart contract.

Out-of-protocol Auction and Free Tickets

To reduce the gas costs of the system, we move from an auction-based system to a posted-price system. In the case of congestion, we assume that blob submitters can attach a priority fee to their order to buy tickets and that builders order transactions with a higher priority fee above those with a lower priority fee.

Since we assume transactions paying a higher priority fee are included over those that pay less, we do not need to charge a price for the tickets. An attacker aiming to prevent rollups from posting blobs needs to outbid rollups who want to propagate their blobs via the vertically sharded mempool regardless of the price of tickets. Congestion would be extremely rare and most likely caused by an attacker since the tickets are k-oversupplied to the maximum amount of blobs and the target amount of blobs is only 2/3rds of the maximum. In other words, the natural demand would have to be 15 times as high as expected to cause congestion (with k = 10).

Note that the worst-case attack would prevent rollups from using the vertically sharded mempool for some period of time. Rollups could still use private builder mempools or calldata to post their data. The worst-case attack is expensive as an attacker either needs to incur costs to outbid rollups or must forgo priority fees rollups are willing to pay.

Free tickets reduces the complexity, and therefore gas costs, of the system because it is not necessary to set a minimum price and no refunds have to be implemented.

Smart Contract Implementation

All of the aboved mempool ticket/lease proposals can be implemented via a smart contract and do not require a hard fork. The smart contract chooses an allocation rule (e.g. LIFO Mempool Leases or the Simple Mempool Tickets). It takes as input orders and outputs a list of sender_IDs that may propagate blobs in the vertically sharded mempool. Nodes then take this list and use it in their execution layer vertically sharded mempool.

Finally, vertically sharding the mempool also does not require a hard fork since it is a networking level change. Vertically sharded mempools do require social coordination since blob submitters must shard their blobs to be able to propagate in the vertically sharded mempool.

Importantly, since mempool ticket allocation will be done via a smart contract, it is relatively easy to change. Suppose that the behaviour of blob submitters changes, the smart contract with the mempool ticket allocation rule can be swapped out for another that better fits the new behaviour.

Comparison to Sparse Blobpool and Horizontal Sharding

In this section we compare a vertically sharded mempool with the sparse blobpool and horizontal sharding proposals. This section assumes familiarity with the vertically sharded mempool, sparse blobpool, and horizontal sharding proposals.

Sparse Blobpool

In a sparse blobpool, nodes download a blob in full with some probability (proposed: p=0.15) and sample it otherwise (p=0.85). That means that the expected amount of data that must be downloaded per blob is 0.15 + \frac{0.85}{8} \approx 25%. In the vertically sharded mempool proposal, it is only \frac{1}{8} = 12.5%. Therefore the vertically sharded mempool reduces the amount of bandwidth nodes need to use in the mempool. This is especially relevant if the sharding factor (8 above) increases further, which is discussed to happen in the future.

An advantage of the sparse blobpool proposal is that it does not change the user experience of blob submitters compared to the status quo. Mempool tickets do change the user experience. Potential iterations on the mempool tickets concept could change the user experience to something that rollups want, such as fixing the blob price in advance.

Horizontal Sharding

In a horizontally sharded mempool, validators use a rule to determine whether to download a blob in full or not at all. The advantage is that the horizontally sharded mempool can be easy to implement since there is no ticketing system necessary to prevent DoS attacks. The disadvantage is that the bandwidth used per node per slot has a high variance, as in some slots a validator may need to download many blobs and in some none.

Importantly, a vertically sharded mempool prevents validators from doing duplicate work since they can download the samples for the blobs they see in the execution layer mempool and do not have to download them again on the consensus layer when the block arrives (assuming cell-level messaging). In a horizontally sharded mempool, validators will do extra work since they download parts of blobs that they do not need in the execution layer mempool and then need to download samples in the consensus layer when the block arrives. Although in FullDAS validators may be expected to custody full blobs as opposed to only samples in PeerDAS, PeerDAS is what is being shipped now and it is unknown when FullDAS may arrive.

Conclusion

Improving the blob mempool is a top priority as today’s mempool cannot sustain a large increase in the number of blobs Ethereum may expect to see soon. Vertically sharding the mempool is an appealing solution as it greatly reduces the bandwidth necessary for the mempool and prevents duplicate work on the consensus layer to do the consensus critical data availability sampling.

The main problem with implementing a vertically sharded mempool is that there needs to be some DoS prevention mechanism. In this work we propose three mempool ticket mechanisms that prevent DoS while enabling a vertically sharded mempool. The main trade-off is between impacting the user experience and the gas needed to operate the mechanism. Table 1 summarizes the properties of this post’s proposals.

| Wholesale Tickets | Mempool Leases (Stake) | Mempool Leases (LIFO) | Simple Mempool Tickets | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gas | Low. Many tickets bought with few transactions. | High. Ideally low lease holder turn-over. Mechanism requires a more complicated smart contract. | High. Ideally low lease holder turn-over. Mechanism requires a more complicated smart contract. | Medium. Simple smart contract but tickets bought in every slot. |

| UX Pro | Many tickets available. | Big rollups may not need to buy tickets every slot. | Big rollups may not need to buy tickets every slot. | Little estimation necessary. |

| UX Con | Rollups risk being censored. | Small rollups need sufficient liquidity. | Small rollups may spend proportionally more on fees for leases. | Need to buy tickets every slot. |

| Other | N/A | N/A | N/A | Hard cap on bandwidth usage. |

Table 1: Summary of the gas and user experience properties of the Wholesale Tickets, Mempool Leases (Stake and LIFO), and Simple Mempool Tickets proposals.

Importantly, ticket mechanisms could be relatively easily exchanged for another if needed since they are implemented via a smart contract and do not require protocol changes. This is especially relevant as not only do mempool tickets change the user experience of blob submitters but so does the large increase in throughput we will see soon. The effect of the interaction between the throughput increase and the mempool ticket on user experience is hard to predict so flexibility on the mempool ticket mechanism is desirable.