Thank you for your contribution to the issuance debate. I will offer some brief remarks on your post, often including links to the issuance reduction FAQ.

Section 2

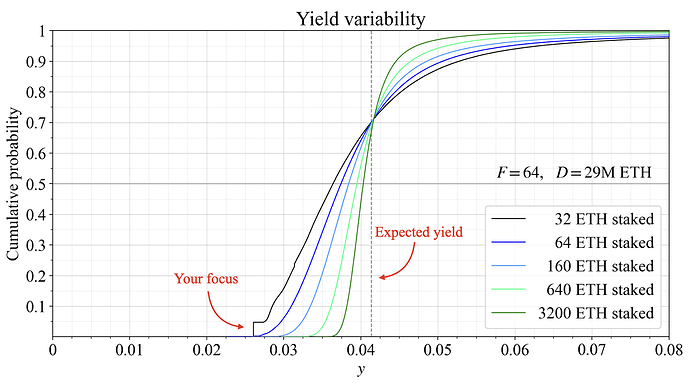

The modeling in Section 2.1.3 is very problematic. It is not correct to base a solo staker’s yield on the short-term median and a delegating staker’s yield on the average. The expected staking yield that solo stakers and staking service providers (SSPs) take home is essentially the same. If the idea is to account for variability in staking rewards for solo stakers, a review of the post on properties of issuance level would be fruitful. Figure 9 in Section 4.2 illustrates how variability in rewards varies with pooling over a year when 29M ETH is staked (based on data of MEV over the preceding year). I reproduce it here and highlight the tiny vertical line segment of the black line, representing only 5 % of 32-ETH stakers over a year. These are the unlucky solo stakers that the text bases its analysis on (note that the expected yield is the same because there are also lucky solo stakers). Over 2-3 years, this vertical line goes away. It would be better to have the expected yield the same for both parties. Variability can still be woven into the argument.

Another remark concerning the model:

If this is so simple, why don’t they do it right now? In any case, note that if node operators raise their commision, the gap between how much of the staking yield that befalls the delegator and solo staker increases. From the perspective of retaining a higher proportion of solo stakers, this could be considered as beneficial.

Concerning Section 2.1.1:

[quote="xadcv, post:1, topic:19992”]

Market forces and fiduciary duties ensure that CEXs like Coinbase squeeze the maximum amount of profit from staking-as-a-service (for their customers and ETF issuers), and long-term the majority of their holdings are staked.

We model the above impact by assigning a 10m staked ETH inflow to Coinbase.

[/quote]

I would expect some actual model here. How do you explain the assigned 10M staked ETH to Coinbase in light of the steady decline among the CEXes in red in the Dune graph in Section 2.1.3 (Coinbase, Kraken, Binance, Bitcoin Suisse)? This decline has taken place even as the staking yield has gradually fallen.

Section 2.1.2 feels like a restatement of the associated discussion in the FAQ. While my biggest concern is the proportion of solo stakers, I still think we can cap the stake, just not at 25%.

Section 2.2.1 “Issuance as a cost is a reductive framing”: does not fully address issuance as a cost, rather just taxes.

This gives a very incomplete picture of issuance policy. The welfare gain to Ethereum from an issuance reduction is addressed in two parts in the FAQ. The first part that we will focus on here explains how reduced costs raise welfare.

In other words, it is insufficient to only address taxes. Relevant costs include hardware and other resources, upkeep, the acquisition of technical knowledge, illiquidity, trust in third parties and other factors increasing the risk premium, various opportunity costs, taxes, etc. We know the cost that the marginal staker assigns to staking from the equilibrium, and can through assumptions regarding the slope of the supply curve quantify the welfare gain from an issuance reduction using the integral of the inverse supply curve. If we force users to choose between incurring costs as stakers, or to subject themselves to increased dilution under equilibrium, they might in the future simply decide to use another blockchain where the imposed costs are lower.

Mostly correct. It is unfortunate that several researchers have pushed this angle without careful consideration, but it is not the fundamental argument for a reduction in issuance policy. The fundamental argument, as previously mentioned, is the cost reduction and macro perspective addressed in the FAQ. In that answer, I outline precisely the topic brought up in Section 2.2.2, highlighting that we must focus on the cost reduction:

Note that to the individual staker, the realization that issuance dilutes them may still be very important. Some stakers may otherwise look only at issuance yield, without considering how the issuance rate increases the inflation rate, ultimately reducing the proportion of all tokens they retain. There is value in highlighting that, even while it is not the reason to reduce issuance. This topic is discussed in a separate answer in the FAQ, also addressing the influence of the slope of the supply curve, as discussed in Section 2.2.2, in the form of an isoproportion map.

In my original thread on minimum viable issuance I captured both the welfare gain (orange area in the figure from the link) and the benefit to the individual staker and non-staker (attainable change in proportion held, which has later been dubbed “real yield” or “proportional yield”) from an issuance reduction in a single graph. This treatment may have led some researchers to not fully appreciate that two separate issues were being simultaneously uncovered.

It is very hard to understand this statement. Retaining a viable application layer is a key reason for pursuing MVI. A situation where some applications can be “held hostage” by an incumbent LST monopoly is scary. It would only benefit the SSPs at the expense of Ethereum’s users. Quoting from the FAQ:

Francesco’s tweet about retaining a trustless asset within Ethereum is particularly astute here.

I find it surprising that people seem to be ok with a future where eth is replaced by LSTs (possibly one, possibly custodial). What good is decentralization of staking if there is no trustless asset? Imho the staking economics debate should focus on this point first

Section 1

Quote from Section 1.3. “There is no future-proof safe level of Security”:

There is value in having a high cost-of-corruption (CoC). However, security needs to be approached holistically. Excessive issuance can render the native token less valuable in the long run, thus reducing the blockchain’s economic security. This is due to the welfare loss associated with compelling users to incur higher costs than necessary for securing the network, as previously discussed. The perspective on economic security I outline in the FAQ seems reasonable in this context:

I recognize that the post indeed takes a different stand on this topic in Section 1.4 and posits that it is instead increased stake participation that is a key to making ETH valuable. Besides the arguments against this that I have presented in my remarks so far, the argument can also be made that beyond certain levels of stake participation, even short-term security begins to degrade. The social layer may lose its neutrality and credibility as the ultimate arbitrator against attacks from dominant SSPs. This argument can be better understood by first analyzing our different positions on the topic as reflected in this part in the end of Section 1.3:

This paragraph implies that the social layer must impose its will through the validator set. However, what is normally meant by the “final defense” is that the social layer can convene to act one layer above the consensus mechanism, in the event of, for example, a 51% attack. People are the last line of defense. In this regard, a proof-of-stake blockchain run by open source developers is certainly not helpless if a large bank were to degrade the consensus mechanism. There are a range of defensive strategies, whose mere existence would presumably scare off any would-be attacker. This leads us to a discussion of the “macro perspective”. A greater concern is namely what would happen if excessive issuance corrupts the social layer:

Section 3

Finally some notes on the conclusions where I somewhat repeat previous answers.

The marginal staker will always have the same cost as revenue under equilibrium—it derives no surplus. An important point of MVI is indeed to reduce costs for Ethereum’s users, thus providing a welfare gain to token holders. It follows from the notion of identical cost and revenue that this must involve a reduction in the marginal staker’s revenue.

Highlighting again that taxes are merely a small part of the costs, as explained in my answer relating to Section 2.2.1.

I am not sure what you refer to by making the network more complex, but building a complex money-lego based on LSTs is in my view very problematic and can impute structural risks on Ethereum.

You can’t. The extra issued ETH will just compel users to take on more and more costs in aggregate (loss of liquidity, hardware costs, taxes, etc.).