I thank participants that have discussed these topics during our recent meetings: Maria, Ansgar, Vitalik, Francesco, Caspar, Julian, and many more.

1. Overview

EIP-8037 harmonizes and raises the gas cost for state creation. A concern is that an increase in the gas cost may impede scaling, as users spend a larger fraction of the gas limit on state creation, crowding out regular gas usage. Therefore, researchers have studied mechanisms for moving state creation gas outside of the targets and limits imposed on all other operations, giving state creation its own target and limit. If 50% of the gas is spent on state creation gas after repricing (up from 30%), then separating out state creation produces around a 100% scaling gain across all other operations, a very tempting proposition.

Three paradigms for how to approach this issue have been suggested. Besides a vanilla repricing, Ethereum could adopt gas metering as in EIP-8011. The gas price could be set to vary dynamically with the gas limit, with one possible specification proposed here and a similar specification also adopted in the latest version of EIP-8037. Metered state creation can as an alternative be used to target some specific state growth with adaptive gas cost, as in EIP-8075.

This post analyzes a specific topic: how the base fee should be updated each block when two separate resources (regular gas and state creation gas) are used. Lessons can be used both for EIP-8011 and EIP-8075, but are the most important in EIP-8011 since it does not have a targeting mechanism to bring resource consumption of the two separate resources to a certain relative level.

First, existing approaches such as applying the max and average function are visualized. Then the Euclidean norm is proposed as a viable compromise solution. Asymmetric approaches are also explored. The more non-linear the metered-gas equation, the more asymmetric it can be, to maximize scaling. Finally, the simplest change: multidimensional gas accounting, is outlined. Throughout this post, metered gas G, regular gas G_1, and state creation gas G_2, are expressed as fractions of the regular gas limit.

2. Max function of EIP-8011

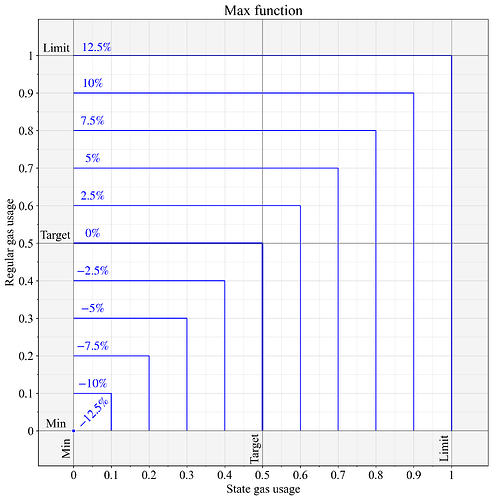

EIP-8011 computes the metered gas G that is fed into the EIP-1559 base fee update formula as the max of the gas used by all separate resources. Figure 1 illustrates the outcome.

One concern is a suboptimal scaling boost. If one resource consumes much more gas than the others, remaining resources can be pushed far below their targets under equilibrium, due to the high base fee relative to demand for these resources. The resource with higher demand remains around its 50% target. Resources that are burst-constrained, such as compute, should ideally be utilized close to their limits, as the available processing power otherwise is left underutilized in most blocks.

Figure 1. Base fee change when applying the max function to compute metered gas of two individually metered resources. According to the EIP-1559 specification, a price change of 0% means that the metered resource was computed to G=0.5, a 12.5% price change is produced from G=1, and -\text{12.5%} implies G=0.

Note that the non-linearity of the max function will lead long-run consumption to be below the targets. Even if the long-run consumption of the two resources is balanced, it will not always be balanced at the individual block level. The price is then set to preserve target utilization only for the more utilized resource. For example, if some blocks are utilized as (0.5, 0.3) and others as (0.3, 0.5), the long run average utilization may only be around (0.4, 0.4).

Further note that the specified gas prices for the two resources may not lead them to both be consumed at the specified “target”. This aspect can both be a benefit and drawback, and can be tuned with a preprocessing step during metering, as discussed in Section 7.

3. Average function of EIP-8075

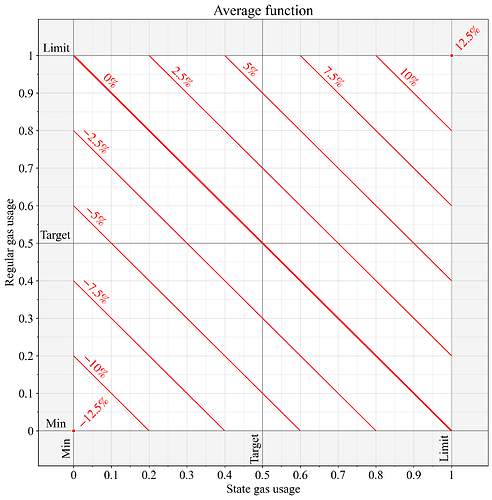

Figure 2 illustrates the metered gas G as the average of the gas used by the two separate resources. This is the approach of EIP-8075 (besides its separate targeting step). With this metering approach, if utilization between the two resources differs under equilibrium, one is pushed above 50% and one below. Concretely, since the system is balanced at (G_1+G_2)/2=0.5, we have G_1+G_2=1. Assuming that the relative difference in utilization remains intact, the outcome is a better preservation of scaling in comparison with the max function, since the total consumed gas remains at 1 (in normalized units).

Another benefit is that both resources always influence the base fee, just as today. The reason for using a dynamic pricing auction in the first place is to surface a fixed price per block that still can vary to keep consumption of burst-constrained resources (such as regular gas) within their limits, and long-run constrained resources (such as state-growth) at their target. To keep state growth close to some specific level, it seems beneficial if the base fee differs when a block consumes the target level of both regular and state creation gas, in comparison with when it only consumes the target level of regular gas and no state creation gas.

Figure 2. Base fee change when applying the average function to compute metered gas of two individually metered resources. According to the EIP-1559 specification, a price change of 0% means that the metered resource was computed to G=0.5, a 12.5% price change is produced from G=1, and -\text{12.5%} implies G=0.

A concern if applying this approach to EIP-8011 is that long run usage of one resource may be pushed very close to its limit. And of course, if more than two resources were to be used in EIP-8011, then one resource may come to fully saturate its limit. The tight limits with two resources are not a concern in EIP-8075 that also uses the average function, since the state creation gas cost quickly adapts to restore equilibrium at 50% utilization for both resources.

4. Solutions in between the max and average

The max and average functions have separate concerns, which could be addressed by positioning the outcome somewhere in between. Scaling is then better preserved, while still not permitting a resource to be pushed very close to its limit in the long run under lopsided distributions.

4.1 Weighted combination of the max and average

A simple solution is a weighted average of the max and average applied to the used gas of the two resource G_1 and G_2:

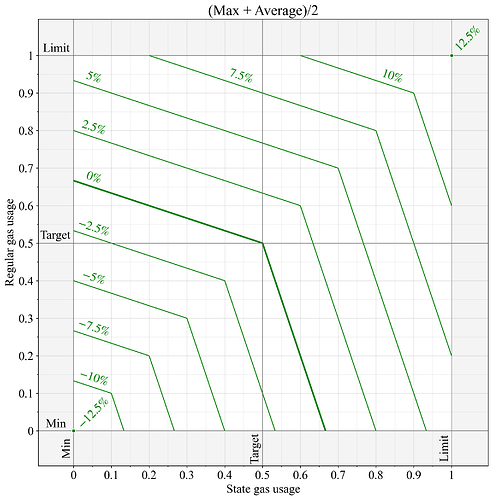

Two possible settings for w are 1/2 and 2/3. Figure 3 shows the outcome under w=1/2, where the full equation thus becomes:

Figure 3. Base fee change when applying a weighted combination (w=1/2) of the max and average function, to compute metered gas of two individually metered resources. According to the EIP-1559 specification, a price change of 0% means that the metered resource was computed to G=0.5, a 12.5% price change is produced from G=1, and -\text{12.5%} implies G=0.

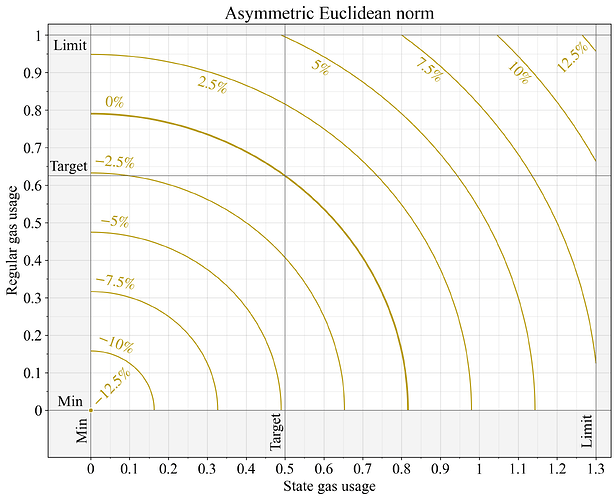

4.2 Euclidean norm

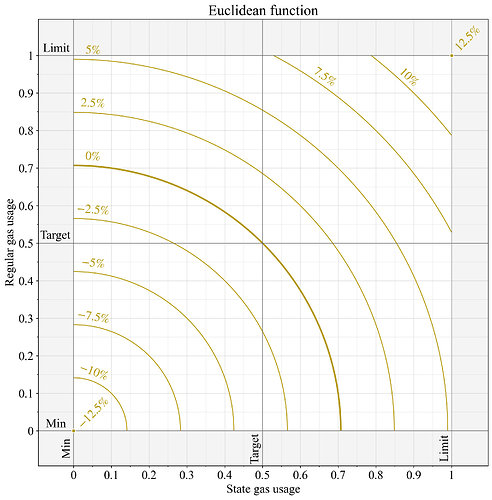

A more refined solution is to rely on the Euclidean norm (L2 norm):

This produces a smooth surface (quarter circle) where each resource’s marginal impact on metered gas is proportional to its current usage:

If the current usage satisfies G_1 = 2G_2, then an additional marginal unit of regular gas increases metered gas about twice as much as an additional marginal unit of state creation gas. The mechanism thus remains most sensitive to the specific resource operating furthest above its target, while still always being influenced by a change in consumption by either resource. Another interesting property is that the Euclidean norm will produce very modest variability drag at the block level when operating close to the target intersection. The Euclidean norm also has intuitive geometrical properties, measuring metered gas as a distance from origin. Figure 4 illustrates this function.

Figure 4. Base fee change when applying the Euclidean norm to compute metered gas of two individually metered resources. According to the EIP-1559 specification, a price change of 0% means that the metered resource was computed to G=0.5, a 12.5% price change is produced from G=1, and -\text{12.5%} implies G=0.

Conceptually, the max, average and Euclidean norm can all be captured by the equation

For the average function, p=1, for the Euclidean norm, p=2, and for the max function, p approaches infinity.

4.3 Joint plot of all functions

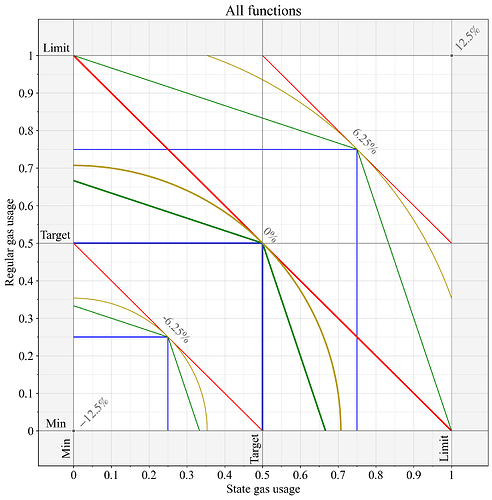

Figure 5 shows the outcomes presented in Figures 1-4 together, for easier comparison. All metered-gas equations produce the same outcome when both resources are used equally, but differ regarding how they react to lopsided utilizations.

Figure 5. Base fee changes of Figures 1-4 presented in the same graph.

5. Asymmetric target/limit ratios

5.1 Motivation

Asymmetric target/limit ratios are also viable. Since state growth is not burst constrained, a higher limit relative to the target can be beneficial. Conversely, since regular gas is burst constrained, it may ideally have its target and long-run average consumption a little closer to its limit, just like blobs today. As previously mentioned, under the average function, pushing the target above half the limit could lead one resource to fully saturate its limit if the other is not used. The target/limit ratio should therefore not be increased when averaging, and it may actually be desirable to decrease it.

For other functions, it is possible to increase the target/limit ratio for the burst constrained resource. One motivation for doing so is that above-target usage of one resource will lower the equilibrium usage of the other. Target usage is just an upper bound with the max function—the actual usage of one resource can fall close to zero under equilibrium if the other resource is relatively more utilized than what was originally foreseen. Furthermore, as discussed in Section 2, uneven utilization at the block level will also serve to push down the equilibrium usage. Thus, the max function would see below-target usage of both resources if they are equally in demand.

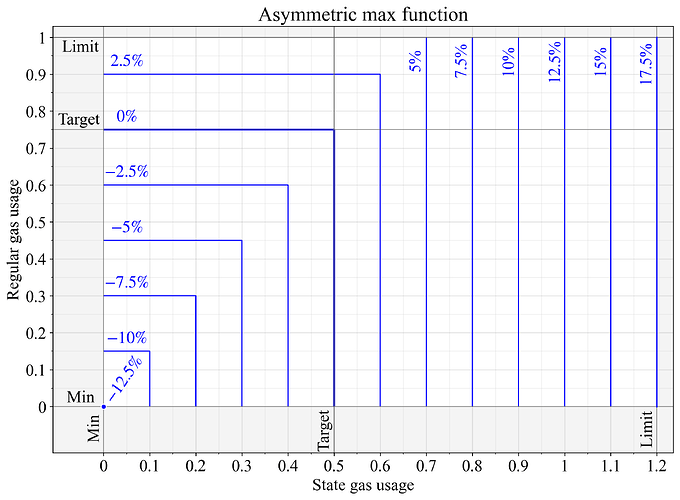

5.2 Asymmetric max

The asymmetric max function in Figure 6 shows the regular gas target positioned 1/4 above the halfway point (at 3/4 of the limit), by applying a preprocessing G'_1 = \frac{2}{3}G_1. This preprocessing makes it such that G_1=3/4 is reset to (3/4) \times (2/3) = 1/2 before applying the max function. State gas has its limit extended by 20% since this resource is not burst-constrained.

Figure 6. Base fee change under an asymmetric max function, that sets the target for regular gas at 3/4 of its limit, and expands the limit for state gas by 20%.

5.3 Asymmetric Euclidean norm

Under the asymmetric Euclidean norm in Figure 7, the regular gas target is instead positioned 1/8 above the halfway point (at T_1=5/8 of the limit). A linear preprocessing step is applied such that one marginal unit of regular gas and state gas have equal impact at the target intersection (T_1,T_2). Consider a preprocessed Euclidean metering equation:

Equal marginal impact at the target means \partial G/\partial G_1 = \partial G/\partial G_2 at (T_1,T_2), which simplifies to

Values for c_1 and c_2 were set such that G(T_1,T_2)=T_2 since T_2 remains unchanged at 1/2. This is achieved at

State gas further has its limit extended by 30% since this resource is not burst-constrained.

Figure 7. Base fee change under an asymmetric Euclidean norm, that sets the target for regular gas at 5/8 of its limit, and expands the limit for state gas by 30%. Preprocessing of the measured gas values ensures that one marginal unit of regular gas and state gas has the same impact at the target intersection (T_1,T_2).

6. Multidimensional gas accounting

The simplest mechanism that can be used for preserving (some) scaling is to rely on the current EIP-1559 mechanism, but to simply count each unit of state gas a little less when aggregating the cumulative gas used in the block. The user still pays the full price for state gas. Thus, the gas_used that the sender pays is computed as normal: gas_used = regular_gas_used + state_gas_used. However, a DISCOUNT_FACTOR (e.g., DISCOUNT_FACTOR = 2) is applied when computing the cumulative_gas_used for the block, that will be counted against the block’s gas limit:

cumulative_gas_used = regular_gas_used + state_gas_used // DISCOUNT_FACTOR

The protocol then does not need to aggregate both resources separately to apply the metered-gas equation at the end, because it does not attempt to uphold separate limits. Of course, this is also to the detriment of scaling, because state gas will still crowd out regular gas (to some reduced extent) under equilibrium.

7. Conclusion

7.1 Comparison between viable options

A few different metered-gas equations were investigated for EIP-8037. At one extreme, metered gas can be computed as the max of both resources. If the target is at half the limit, one resource might then be consumed at a very low level under equilibrium, since the resource with higher demand cannot exceed its target in the long run. To compensate for this, it is however possible to move the target level closer to the limit for the burst-constrained regular gas, in order to preserve scaling, should state creation be much more in demand than anticipated after repricing.

At the other extreme, the metered gas can be computed as the average of both resources. When one resource is relatively more in demand than the other, its long-run usage can increase somewhat, allowing the less used resource to not be pushed as low under equilibrium. On the other hand, the target for regular gas cannot reasonably be set asymmetrically closer to its limit, since the long-run equilibrium usage may already be pushed close to 1, should regular gas be much more popular than state creation gas.

A compromise between the two extremes can be computed as a weighted average or the Euclidean norm. These compromises permit an asymmetric target/limit ratio, albeit more contained than when using the max function.

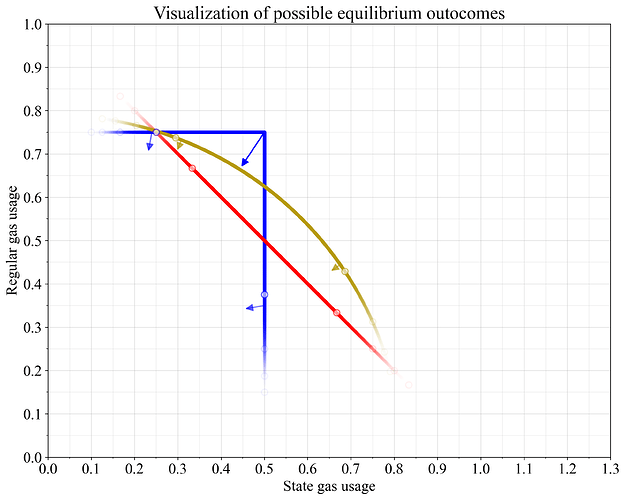

Figure 8 shows all three options, previously presented in Figures 2, 6 and 7, focusing only on the equilibrium points where the base fee is unchanged (0%). An important aspect is how the system behaves when demand between resources turns out to differ from assumptions researchers have made beforehand (particularly when demand is initially assumed to be at the target level for both resources). The outcome at equilibrium utilization ratios between the two resources of {2:1, 3:1, 4:1, 5:1} are therefore marked with circles. For visualization purposes, the opacity of the different lines was set using a normal distribution, with each integer increase to the ratio (each circle) representing one standard deviation.

As discussed in Section 2, the non-linearity of the max function will push down the equilibrium utilization, especially at the target intersection. This feature is illustrated by arrows. The effect is strongest for the max function close to the target intersection. Under the average function, a block-level mismatch instead pushes long-run utilization to move along the 0% line, instead of orthogonal to it.

Figure 8. Illustrating possible outcomes for metered-gas equations studied in this post. Circles show the equilibrium outcome when one resource is consumed at ratios {2:1, 3:1, 4:1, 5:1} relative to the other. Arrows capture the notion that the long-run utilization falls when individual blocks do not have an even resource distribution under non-linear metered-gas equations.

7.2 Demand, targeting and changes to the gas limit

A problem with metering approaches as in EIP-8011, that is not evident in EIP-8075, is the difficulty in predicting how a change in price will affect demand. Whatever metered-gas equation that is adopted, researchers will have to account for how they believe the new effective gas price will affect demand, to then design the processing that takes place based on that.

It can be noted that the demand at a certain gas price will not necessarily match the “target” set by the protocol. There is no complete “targeting” as in EIP-1559, EIP-4844, or EIP-8075, where the price is varied to ensure a certain utilization. If state gas is only demanded at a proportion of 3/7 relative to regular gas, then, ignoring block variability, consumption of state gas would not affect the gas price under a max function even if it doubled. To have state gas metered at a level where it may always affect the gas price (and thus constitute actual targeting), a transfer function could be adopted, where gas is measured and charged at different levels. The user would pay for its transaction at the stipulated gas price, but the max function could for example be applied to a gas metered at a 7/3 higher level.

This strategy is somewhat similar to the normalization step performed for the asymmetric ratios in Section 5, but then applied also under a symmetric ratio to compensate for demand not situated at the target. However, this also means that state creation would have an outsized impact on the overall gas price relative to how much users pay for that gas. When considering this aspect, something less strict than the max function looks a bit more attractive under lopsided demand. Section 6 is also relevant as a comparison here, in that it reduces the impact of state creation gas on pricing. Such an approach could also be applied under, e.g., the average function.

A related issue is how to deal with changes to the gas limit. As the gas limit rises, state creation would rise with it. To keep state creation under check, one solution is to adjust its gas price with changes to the gas limit, for example, as done here. Just as it is difficult to predict the effect of a one-time repricing on demand, it is equally difficult to predict the effect of such a gradual change. It is not as simple as doubling the gas price for state creation when the gas limit doubles. The correct change depends on demand elasticity, and it is at this point rather difficult to make predictions on this matter. However, a best-effort attempt can of course be made, and then adjusted at the next hard fork as elasticities have been observed. This is generally the approach that will have to be taken under a multidimensional metering, concerning many of the assumptions made in the initial hard fork.