Thanks to Julian Ma, Benedikt Wagner and Justin Florentine for feedback and review. Thanks also to participants of the early January Berlin sessions where certain properties of the design were discussed: Julian, Thomas, Justin, Vitalik, Caspar, Marios, Ansgar and Francesco.

1. Overview

This post introduces LUCID, an encrypted mempool design that bridges the gap between includer and proposer, while adhering to existing Ethereum mechanisms such as ePBS, BALs, and auditable builder bids (ABBs). The design is general purpose and can be used for, e.g., trustless self-decryption by the sender, decryption by a trusted party, or in threshold designs. LUCID is an acronym capturing key features:

- IL – The design relies on inclusion lists (ILs) enforced by the fork-choice, like FOCIL, but tentatively modified to grant includers more equitable inclusion rights as well as encryption capabilities for MEV protection. Includers thus act more like proposers. The ILs can be staggered to improve censorship resistance, facilitate decentralized inclusion preconfirmations, and reward includers without inducing networking inefficiencies.

- U – Two IL design options are considered: a Uniform price auction over inclusion lists (UPIL), which ranks transactions based on the fee that senders offer for inclusion; Unconditional ILs (UILs), where the includers determine priority order for their own list.

- C – The ILs can carry Ciphertexts in sealed transactions (STs) that are propagated in an encrypted mempool and can be bundled. The STs are committed to in the ABB.

- D – The payload is propagated in a Distributed fashion and only includes references to IL transactions in the network representation. The consensus representation remains a self-contained execution payload, and includes ST tickets used for debiting ST senders as well as the decrypted STs.

Many of the components described in this post can be adopted separately or together. For example, it is possible to run only the encryption scheme without distributed payload propagation (DPP); the only downside is worse broadcast efficiency. The timeline for LUCID is presented below.

Section 2 introduces the reader to the problem that is addressed and Section 3 takes a closer look at the encryption design. Section 4 presents DPP and Section 5 discusses how reveal optionality is dealt with in the design. Section 6 finally offers a brief discussion, where Section 6.1 details how a minimum viable EIP could be structured. Appendix A completes the vision for DPP by proposing staggered inclusion lists (SIL), where includers gradually build the payload during the slot. Appendix B presents a tighter design where STs to be decrypted are specified in the payload as opposed to in the ABB. Appendix C finally shows one decryption scheme that decryptors could deploy.

Timeline

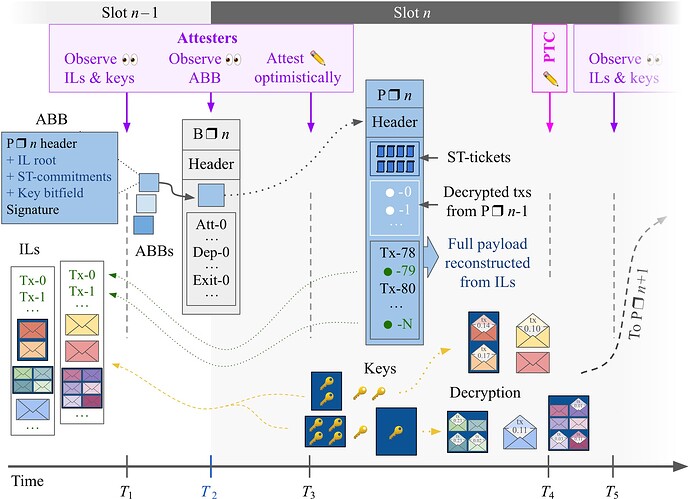

Figure 1 provides an overview of the LUCID mechanism.

Figure 1. LUCID timeline. Builders produce ABBs with commitments to sealed transactions. These ABBs are included in the beacon block to allow decryptors to release keys in a timely manner before the next slot starts. Transactions listed in ILs can be included in the payload by reference.

- Before T_1 – Includers propagate ILs that, besides plaintext transactions (PTs), can incorporate STs. The STs are either included individually or in a bundle (dark blue background), and can be sourced from a public encrypted mempool. Each ST consists of a signed ST ticket used for charging the sender and binding to a decryptor as well as the ciphertext

encrypted_txalso included in the ST. Theencrypted_txdecrypts to a signed PT that can have a differentfromfield than the ST, together with aToB_fee_per_gasthat will be used for ordering the PT top-of-block (ToB) once decrypted. Senders encrypt transactions to a decryptor in an open design following the decryptor’s off‑protocol instructions (and if applicable, using its public key), or can otherwise self‑decrypt trustlessly. Appendix A describes how the ILs could be staggered to achieve better coverage and Appendix C gives an example encryption design the decryptor could deploy. - T_1 – Attesters (purple) of slot n freeze their view of propagated ILs as well as the decryption keys for the previous block.

- After T_1 – Once builders are confident they have observed all relevant ILs and keys (those in the frozen view of most attesters), they cast ABBs (an expanded

ExecutionPayloadBid) for the right to build the block (blue rectangles). These ABBs contain “ST-commitments” of the hash of the STs and ST bundles in the ILs. The ABB also flags observed decryption keys from the previous slot. - T_2 – At the start of slot n, the proposer selects a winning ABB, which is at least as encompassing as its own view of required ILs and keys. It includes that ABB in the beacon block.

- After T_2 – Upon observing the ABB, nodes begin requesting any missing ILs as well as ST bytes that are referenced by the ABB’s ST‑commitments. Senders and decryptors can also independently propagate those bytes now.

- T_3 – Attesters of slot n cast a vote on the current head of the chain. If the beacon block is missing or if the included ABB fails their audit due to left out ILs or keys from their frozen view, they indicate the preceding block that is the head of the chain in their view. If the ABB passes their audit, they optimistically attest to the block.

- After T_3 (Payload release) – The builder releases the payload which also carries ST tickets. The first transactions (white rectangle) are decrypted STs, previously committed to in block n-1, ordered by their decrypted ToB fee per gas. Regular PTs from the current slot follow (black rectangle), ordered freely by the builder. The builder references the IL transactions by index into the IL instead of propagating them anew (using a separate list in the network representation).

- After T_3 (Payload reconstruction) – Each client resolves the IL transaction references against its local cache of ILs as well as ST-commitments and assembles the full payload. It computes and verifies the payload root and proceeds to execute the payload. The STs selected by the included ABB for next-slot decryption are represented in the execution payload by a list of ST tickets, which are charged according to their full specified

gas_limit. - After T_3 (Key release) – Each decryptor observes the ST-commitments in the ABB that was included in the beacon block. It confirms that the ABB has correct data for its own ST-commitment (pertaining, e.g., to its

gas_obligationspecifying how much gas it consumes), that the aggregate of allgas_obligationentries is within the allotted share of the next payload (ToB_gas_limit), and that the beacon block is attested to. It propagates the signed key(s) that reveal the STs that fit into the next block. The key(s) are flooded P2P and observed by attesters of the next block before their deadline at T_5. The ToB of payload n+1 can then be constructed with the decrypted STs ordered ToB. - T_4 – The payload timeliness committee (PTC) votes for the timeliness of the payload. Given the distributed design, the ILs carrying transactions referenced in the payload or the committed full STs/ST-bundles must by this point also have reached the PTC member for the vote to indicate a timely payload.

- T_4 or T_5 – The deadline for the released keys can be enforced either by a PTC bitfield vote on their timeliness, or by attesters of slot n+1 freezing their view of the released keys and using view-merge. Attesters vote on the next ABB contingent on adherence to either the PTC bitfield vote or the frozen key view.

- After T_5 – The process follows the same trajectory as after T_1 (for the previous slot). The decrypted STs from slot n are added ToB, ordered by ToB fee and charged that fee. Given that the STs are decrypted before block n is constructed, the design is fully compatible with BALs: the builder of block n+1 executes and prepares the BAL as normal.

2. Introduction

A concern for decentralized blockchains such as Ethereum is the monopoly that the single proposer has over transaction inclusion in each block, which may lead to censorship and suboptimal user welfare. For this reason, designs with multiple concurrent proposers (MCP) have been proposed (1, 2, 3, 4). Years of research into inclusion lists (ILs) (e.g., 1, 2) in parallel led to the Fork-choice enforced inclusion lists (FOCIL) design. FOCIL has via EIP-7805 gained ground as the primary option for facilitating censorship resistance (CR) in Ethereum, allowing several includers to propagate ILs of transactions to be included in the next block. However, when the block is full, the proposer still has the right to censor transactions, even if they are willing to pay more than the transactions that actually are included. Furthermore, a large proportion of censorable transactions must be propagated privately to avoid MEV, and can therefore not rely on FOCIL for CR.

Various IL designs that give the proposer less leeway in controlling the content of the block have been proposed. Unconditional ILs (UILs) require all listed transactions to be included, if they meet regular inclusion criteria. EIP-8046 introduced a Uniform price auction over inclusion lists (UPIL), which ensures that the proposer no longer can ignore the ILs when the block is full. Transactions are ranked by the fee they offer to pay, and those willing to pay the most are included, each paying the same uniform intra-block base fee, which is burned. This provides strong CR and is beneficial for time-sensitive transactions and a multidimensional fee market. Still, UILs and UPIL do not prevent MEV because transactions must still be propagated openly.

To prevent MEV, transactions must remain hidden until they are committed to. Various designs have been proposed for encrypted mempools, such as threshold encryption potentially leveraging proposer commitments, commit–reveal schemes as in Sealed transactions, or a hybrid of the two. Sealed transactions may under ePBS leverage ABBs. A commit–reveal scheme under fork-choice enforcement, as in sealed transactions, can further facilitate a wide variety of out-of-protocol encryption schemes—a form of generalized sealed transactions. A design in this direction but with same-slot decryption has also been proposed recently as a research post and EIP. Another strategy is to rely on smart-account encrypted mempools, which has also been proposed as an EIP.

A Hayekian argument for decentralized block-building is that a broader set of participants jointly will have the knowledge required for making a good block. It can be noted that only by shielding individual participants’ contributions to that block from MEV and guaranteeing inclusion for viable transactions do we actually enable them to communicate that knowledge in a trustless fashion.

Inclusion lists generally introduce data redundancy: transactions are gossiped in the mempool, then via the IL, and finally gossiped again inside the execution payload. By instead treating the inclusion list gossip as a “pre-fill” step, the payload can be effectively distributed across the slot duration rather than burst-propagated at the end. Transmission of the same bytes twice (once in IL gossip, once in the payload envelope) within a single slot window is thus avoided. Reducing the size of the ExecutionPayloadEnvelope minimizes propagation latency, allowing for shorter slot times, bigger ILs, or bigger blocks. The design is compatible with payload chunking (1, 2), which would simply operate on already somewhat compressed payloads under DPP.

While DPP increases network efficiency, it does not resolve the inefficiency of several ILs propagating the same transactions. It is desirable to come up with an in-protocol solution that decreases the overlap, and this post proposes staggered inclusion lists (Appendix A) to this end, which also facilitate trustless preconfirmations. To limit the number of independent decryption keys that must be reconciled before execution, the STs can be bundled before being committed. This post proposes LUCID, which realizes generalized sealed transactions (extending on 1, 2) while upgrading includers to shield transactions from MEV and to have equal rights to blockspace, thus bridging the gap between includer and proposer.

3. Encryption design

The encryption design is first described using the UPIL mechanism, and the changes required for the UIL mechanism are presented in Section 3.10. Vanilla FOCIL (conditional ILs) can also be used under the general design. It can be emphasized that several of the features outlined in Sections 3-4 such as DPP, UPIL, and bundles are not critical for a baseline LUCID encrypted mempool, as furhter discussed in Section 6.1.

3.1 Sealed transactions

A sealed transaction (ST) consists of a signed ST ticket and a ciphertext encrypted_tx. The ST has the following fields:

fromwhich signs the ST ticket and pays the fees,- regular fields

nonce,gas_limit,max_fee_per_gas,max_priority_fee_per_gas,max_ranking_fee_per_gas, decryptor_addressof the entity responsible for decryption,decryptor_feethat will be paid upon execution of the decrypted plaintext transaction, under the condition thatfromis funded.reveal_commitment, wherereveal_commitment = hash_tree_root(RevealCommitmentPreimage(ticket.from, ticket.nonce, plaintext_tx, ToB_fee_per_gas))binds the revealed plaintext payload to a specific paid ticket,ciphertext_hash, whereciphertext_hash = keccak256(encrypted_tx)binds the ciphertext bytes,encrypted_tx, which decrypts toRevealedTransaction(plaintext_tx, ToB_fee_per_gas).

In the spirit of promoting a general solution, the baseline idea is that the protocol only specifies how clients parse and open the encrypted_tx, while leaving it up to decryptors to define (off‑protocol) which key‑escrow/hybrid encryption construction they use. Concretely, encrypted_tx is an envelope:

encrypted_tx = header_len:u16 || header || ct_dem

ct_dem = nonce || aead_ciphertext

The header is opaque to the protocol and may contain any decryptor‑specific metadata needed to recover the DEM key (e.g., a hybrid public key encryption (HPKE)/KEM encapsulation, threshold ciphertext under a threshold decryptor key, etc.). Decryptors publish off‑protocol instructions describing how senders populate the header and how the DEM key k_dem is derived for a given ticket. At reveal time, the decryptor releases only this per‑ticket DEM keying material (k_dem) so that anyone can decrypt ct_dem and validate the reveal against reveal_commitment.

Decryptors should ensure the released k_dem is context‑bound to the paid ticket (e.g., by deriving it using a domain‑separated encoding of (chain_id, ticket.from, ticket.nonce) as KDF input (HPKE info if using HPKE) and/or AEAD associated data). This makes the revealed key ticket‑specific, so releasing the decryption material for one ticket does not help decrypt ciphertexts attached to other tickets even if header bytes are copied across tickets (any long‑term secret recovered from the header must never be revealed). Appendix C gives one example of such a construction (h/t Benedikt Wagner). For trustless self‑decryption, the sender can keep things simple (e.g., set header_len = 0 and choose a fresh per‑ticket DEM key directly).

class RevealedTransaction(Container):

plaintext_tx: Transaction # Type 2 transaction

ToB_fee_per_gas: uint64

class RevealCommitmentPreimage(Container):

ticket_from: ExecutionAddress

ticket_nonce: uint64

plaintext_tx: Transaction

ToB_fee_per_gas: uint64

class STTicket(Container):

from: ExecutionAddress

nonce: uint64

gas_limit: uint64

max_fee_per_gas: uint64

max_priority_fee_per_gas: uint64

max_ranking_fee_per_gas: uint64

decryptor_address: ExecutionAddress

decryptor_fee: uint64

reveal_commitment: Bytes32

ciphertext_hash: Bytes32

signature: Bytes65 # Signature by `from` over the ticket fields

class SealedTransaction(Container):

ticket: STTicket

encrypted_tx: ByteList[MAX_ENCRYPTED_TX_BYTES]

The gas_limit must be sufficient to cover the calldata cost of the byte size of the encrypted_tx, is bounded by MAX_TRANSACTION_GAS_LIMIT, and will be charged in full—there is no refund upon observing actual gas usage after execution. The decrypted plaintext_tx inside RevealedTransaction is an EIP‑1559 (type 2) transaction with max_priority_fee_per_gas = 0, max_fee_per_gas = 0 (since the decrypted transaction has already been prepaid by the ST ticket), and gas_limit = ticket.gas_limit.

The ST ticket’s nonce reuses Ethereum’s normal account nonce and is consumed regardless of whether the ciphertext is later revealed, since STs are charged regardless of execution success. The ST sender signs the ST ticket. The signature is computed over a domain‑separated digest that includes chain_id (and fork/version) and the hash-tree-root of the ticket fields (excluding signature).

The plaintext payload inside encrypted_tx is separately signed by the plaintext sender as part of plaintext_tx. Nodes validate an ST by verifying the ticket signature and checking that ciphertext_hash matches the hash of encrypted_tx.

3.2 Bundles of sealed transactions

Sealed transactions are committed to in the ABB. Should the encrypted mempool become popular, the large number of separate commitments and decryption keys may put strain on the network, particularly as Ethereum scales. There are thus reasons to limit the number of commitments to STs in the ABB, while still facilitating high throughput. Therefore, STs can be bundled together and committed to jointly.

All transactions of a bundle must have the same decryptor_address and the bundle must be signed by the entity in control of the decryptor_address. It is possible to let bundles carry the full STs, or simply contain hashes with a signature over the hashes. This leaves it up to the includer to reconstruct the full ST bundle. It seems reasonable to require ILs to carry the full ST bytes, given that these must be available by the PTC deadline. If the IL referencing the bundle is unavailable upon being observed in the beacon block, the full bundle must be propagated P2P.

The ability to include non-bundled encrypted mempool transactions is still beneficial for three separate reasons:

- any ST can be executed if included in an IL, providing spam resistance to the public mempool,

- designs such as threshold decryption can run without a sequencer that bundles transactions ex-ante,

- users do not need to propagate bundles for single STs they wish to decrypt trustlessly.

3.3 ST-commitments

Sealed transactions are committed to in “ST-commitments” in the ABB, either individually, or as part of bundles sourced from the public encrypted mempool (or possibly provided out-of-protocol, potentially then leveraging designs similar to MEV boost). Inclusion lists provide an important inclusion path for ST-commitments—the builder must adhere to the commitments they propose. Each ST-commitment specifies four fields:

class STCommitment(Container):

bundle: bool # False if ST, True if ST-bundle

commitment_root: Bytes32 # ticket_root if ST, bundle_root if bundle

decrypt: Bitfield # indices to release keys to decrypt the tx

gas_obligation: uint64 # sum of gas_limit over entries with decrypt=1

An ST-commitment is identified via the commitment_root, which is either the SSZ hash-tree-root of the signed ticket ticket_root = hash_tree_root(STTicket) or of the signed bundle, bundle_root, which covers all ticket_root entries in the bundle. A possible scheduled_root over ticket_root entries with decrypt=1 is discussed in Section 6.3. Note that the ciphertext bytes are bound to the ticket via ciphertext_hash = keccak256(encrypted_tx), which is included in the signed ticket.

3.4 Allotments and ToB gas limit

Each IL has an allotment of ST-commitments, which can initially be set rather low; for example, each IL may commit MAX_COMMITS_PER_IL = 4 ST-commitments. It is possible to enable the builder to make commitments of its own, for example MAX_COMMITS_PER_IL ST-commitments as well. However, for design simplicity, it may be easiest to then simply give the builder its own IL. There is a max_bytes_per_inclusion_list allotment for each IL, just as in FOCIL. It varies with the gas limit so that includers are not disadvantaged relative to the proposer when the block’s gas_limit increases. It can be computed as max_bytes_per_inclusion_list = gas_limit/(IL_COMMITTEE_SIZE * GAS_PER_AGG_IL_BYTES). Setting GAS_PER_AGG_IL_BYTES = 2**9 gives an IL byte-size of 7.15 KiB at a gas limit of 60M when using IL_COMMITTEE_SIZE = 16 as in FOCIL. The ST-commitments still count against the max_bytes_per_inclusion_list.

Each block has a ToB_gas_limit for the decrypted transactions, set to some fraction of the overall gas_limit of the previous block, tentatively 1/4 * gas_limit. There is also a ToB_marginal_ranking_fee_per_gas, computed as the maximum of the marginal_ranking_fee_per_gas of the current block (as specified in EIP-8046) and the ranking_fee_per_gas of the highest-ranked ST excluded from the ToB_gas_limit allocation for the next block.

3.5 Auditable builder bids (ABBs)

The builder makes auditable builder bids (ABBs) for the right to build the payload. The ABB extends the ExecutionPayloadBid by including a ToB_marginal_ranking_fee_per_gas, ST-commitments and a bitfield on key adherence for ST-commitments of the previous block:

class ILCommitments(Container):

IL_root: Bytes32

commits: List[STCommitment, MAX_COMMITS_PER_IL]

class ILKeyAdherence(Container):

key_adherence: List[Boolean, MAX_COMMITS_PER_IL]

class ABB(Container):

... # existing fields of the ExecutionPayloadBid

ToB_marginal_ranking_fee_per_gas: uint64

IL_data: List[ILCommitments, IL_COMMITTEE_SIZE]

key_adherence: List[ILKeyAdherence, IL_COMMITTEE_SIZE] # one bitfield per previous IL in a list of bitfields

The builder deduplicates the STs of the ST-commitments using (ticket.from, ticket.nonce). There can only be one ST with the same (ticket.from, ticket.nonce) in the deduplicated set that should go into the payload, having a decrypt bit set to 1. All other STs with the same (ticket.from, ticket.nonce) must have their decrypt bit set to 0. Furthermore, STs that generate an invalid ticket-nonce sequence for ticket.from, or that are not chargeable at the start of ticket charging (Section 3.9), are also removed in the same way. A deterministic rule for determining which ST to retain during deduplication is applied, selecting the instance in the bundle with the most STs and tie-breaking by the IL’s committee_index.

If there is more than one IL commitment to a specific ST-bundle, the duplicate commitments set decrypt to the canonical zero encoding 0 (a single-bit 0) to save space, and only the ST-bundle from the IL with the highest committee_index remains. To avoid malleability, when decrypt has no set bits it must be encoded as exactly 0 (single-bit 0) and interpreted as an all-zero mask regardless of bundle length; other all-zero encodings are invalid.

For duplicate STs within bundles, all share the same decryptor_address, making deduplication strictly an accounting matter for the decryptor. Further note that the builder is not free to set decrypt bits as it pleases. The attesters, builders (and all other nodes) for slot n+1 will review that the decrypt bits were set strictly to facilitate the deterministic rules (for, e.g., deduplication), without leaving out valid STs surfaced by an IL. If the payload fails their audit, the protocol enters the recovery process under invalid payload, as described in Section 4.5.

Deduplicated STs are finally included by setting decrypt = 1 if their ranking_fee_per_gas exceeds the ToB_marginal_ranking_fee_per_gas, tie-breaking by ticket_root. After determining which STs to include, the gas_obligation is set for each ST‑commitment as the sum of all gas_limit entries with decrypt = 1 in that commitment. The ToB_marginal_ranking_fee_per_gas can further be used for compressing the decrypt bitfield to only span the permissible range of transactions that have a sufficient ranking_fee_per_gas.

The commitment_root in the ABB allows the decryptor to identify it and release the decryption keys upon observing a timely beacon block, even before the payload is released. Each IL_root is included in the ABB to resolve ambiguity under equivocation, as further discussed in Section 4.3 that deals with DPP.

Two methods can be used to keep builders from having to propagate the full ABB for each bid. The builder could specify the delta relative to its previous bid for each new bid, including a hash for reference. It can be expected that ST-commitments are established well before the bid deadline, meaning that the delta in later bids only needs to cover changes to bid values and payload from late-arriving PTs. The other option is to institute a pull-scheme, where builder bids are lightweight, and the proposer pulls the ABB from the winning builder before publication.

3.6 Attestations

Attesters compare the ABB with the ILs they have observed. They verify that:

- the aggregate of all

gas_obligationentries is within theToB_gas_limit, - every timely observed IL without equivocations is correctly specified in the ABB, given the announced

ToB_marginal_ranking_fee_per_gas.

Inclusion lists in the ABB that attesters have not observed are not reviewed. Nodes request these ILs after observing them in the ABB and the PTC will eventually vote on their timeliness.

3.7 Key release

The decryptor observes the ToB_marginal_ranking_fee_per_gas and its stipulated gas_obligation in the ABB propagated with beacon block n. It verifies that the ToB_marginal_ranking_fee_per_gas and decrypt bitfield indeed produces the specified gas_obligation for its own ST-commitment and that the aggregate of all gas_obligation entries is within the ToB_gas_limit. This is a requirement for releasing the decryption key(s). Specifically, if the payload then turns out to be invalid or untimely, the decryptor’s ST-commitment will always fit within the ToB_gas_limit. This means that they can still be included ToB in the next valid payload, as further discussed in Section 4.5.

If the IL responsible for listing the ST (or bundle) is not available, the decryptor will at this point (if not done earlier) broadcast the full ST bytes (or bundle body) whose ticket_root/bundle_root matches the commitment_root in the ABB, such that nodes can validate the released key(s) by the PTC deadline. When the decryptor (or anyone) provides the full SealedTransaction bytes for a committed ST, nodes check that hash_tree_root(st.ticket) == commitment_root and keccak256(st.encrypted_tx) == st.ticket.ciphertext_hash. When the decryptor is confident that the beacon block will become canonical (for example after observing attestations for it), it releases its key(s).

At key‑release time, the decryptor publishes the symmetric keying material as described in Section 3.1. Keys are released in a message that is signed by the decryptor_address and identifies the associated ST-commitment by committee_index and commit_index, further including the slot number and the beacon_block_root of the beacon block that carried the associated ABB. For bundles, keys are wrapped in a list of the same length as the number of decrypt bits set to 1, ordered the same way as in the committed bundle.

Key messages are flooded P2P. Nodes relay any well‑formed key message that targets a commitment present in the ABB identified by (beacon_block_root, slot) and is signed by the decryptor_address specified in the ST-commitment. A key is valid if it decrypts the committed ciphertext to RevealedTransaction(plaintext_tx, ToB_fee_per_gas) such that hash_tree_root(RevealCommitmentPreimage(ticket.from, ticket.nonce, plaintext_tx, ToB_fee_per_gas)) == ticket.reveal_commitment, and the decrypted plaintext_tx satisfies the required fixed fields (max_priority_fee_per_gas = 0, max_fee_per_gas = 0, and gas_limit = ticket.gas_limit). The decrypted plaintext sender and nonce are not required to match the ST sender’s from and nonce.

Keys targeting the same beacon_block_root, committee_index and commit_index that are not byte-identical are an equivocation. Equivocated keys are treated similarly to IL equivocation in FOCIL: nodes propagate the first two distinct signed key messages they have observed for the same target to signal equivocation, and the builder is free to ignore the STs that the decryptor equivocated on. Attesters accept such omission if they have observed the equivocation evidence by their attestation deadline.

3.8 PTC vote

The PTC votes on DA pertaining to the payload broadcast and blob data. To comply with the distributed propagation of the payload (Section 4), the PTC vote also pertains to the availability of all data needed to reconstruct the committed ExecutionPayload: the referenced plaintext transaction bytes (tx_reference) and the referenced ST‑commitments and the underlying ST/bundle bytes referenced by those commitments.

It is thus the builder’s responsibility to ensure that the ILs it registered in its ABB have arrived by the time the PTC votes, but the decryptors can also independently propagate the corresponding ST bytes if ILs are unavailable. Further considerations on this topic are discussed in Section 4.3. Upon reconstructing the payload with the aid of stored ILs, PTC members verify that the root of the payload is correct. They also confirm with their vote that the ABB was correctly specified, as can be observed in the payload.

Optionally, each PTC member also broadcasts a signed bitfield indicating which ST‑commitments scheduled for next‑slot decryption had a valid key message observed by the key deadline. The bitfield is indexed over the scheduling ABB’s ST‑commitments with a non‑zero decrypt mask, in canonical order by (committee_index, commit_index) (i.e., by scanning IL_data in increasing committee_index and commits[] in increasing commit_index). The reasons for using the PTC vote are discussed in Section 6.3.

The builder and slot n+1 attesters take a decision on timeliness informed by the PTC vote. To merge views, attesters may freeze their view of PTC votes before the start of slot n+1. The builder may then get to enforce its view on timeliness when a key gets between e.g. 45-55% of the vote (below 45%, attesters enforce untimely; above 55% attesters enforce timely, as long as they have observed the key themselves by the voting deadline). Optionally, the builder may have the ability to propagate a separate structure with its observed votes for merging views.

3.9 Payment and inclusion

The consensus representation of the execution payload is extended with an st_tickets list and a decrypted_transactions list (both described in Section 4.2). These are used for charging the STs.

Charging ST tickets

Each ST ticket in st_tickets debits ticket.gas_limit * (base_fee_per_gas + ToB_marginal_ranking_fee_per_gas) + ticket.decryptor_fee from ticket.from, where ToB_marginal_ranking_fee_per_gas is taken from the ABB whose ST‑commitments scheduled that ticket (i.e., the ABB that defines the pending set). There is no refund in block n+1 based on the actual gas_used, and if the ST is not decrypted, only the decryptor_fee is refunded. A block is invalid if any ticket in st_tickets cannot be fully charged.

Nodes verify that the ToB_marginal_ranking_fee_per_gas (see Section 3.4) was set correctly by comparing it to the ranking_fee_per_gas of the highest ranked validly includable ST excluded from the ToB. Since STs are charged based on their publicly visible gas_limit rather than actual gas used, the fundability check at commitment time is static and does not depend on execution of other transactions. This avoids the circular dependency issues that necessitate conservative balance checks in UPIL’s ranking mechanism.

Including and charging decrypted STs

Nodes observe the release of the keys and decrypt the ST transactions locally. The builder of block n+1 gathers all keys it can find and produces an ABB containing a bitfield with the valid keys it adheres to. Attesters require that the builder adheres to all timely valid keys, where timeliness is determined via view-merge or a PTC vote as previously outlined. The STs that cannot be decrypted with the released key are ignored.

Nodes validate each decrypted ToB transaction against the specific ST ticket that produced it (via the full ST and the corresponding key). The reveal is valid only if hash_tree_root(RevealCommitmentPreimage(ticket.from, ticket.nonce, plaintext_tx, ToB_fee_per_gas)) == ticket.reveal_commitment and the decrypted plaintext_tx satisfies the required fixed fields (max_priority_fee_per_gas = 0, max_fee_per_gas = 0, and gas_limit = ticket.gas_limit).

The first step of processing the decrypted_transactions is to refund the ticket.decryptor_fee for all STs that were not decrypted. The senders are identified as those with indices missing from ticket_index (Section 4.2). The decryptor_fee from decrypted_transactions is instead credited to the associated ticket.decryptor_address. The protocol finally deducts and burns the ToB fee ticket.gas_limit * ToB_fee_per_gas from ticket.from. If the ticket.from cannot cover this fee, the transaction is not included.

Users submitting multiple STs whose decrypted plaintext_tx have the same from and have sequential nonces should ensure ToB_fee_per_gas is nonce‑compatible, since decrypted transactions are ordered primarily by ToB_fee_per_gas while execution still respects per‑sender nonce order.

3.10 Unconditional IL version

For the unconditional IL version, a few modifications are made, which are here detailed. The idea is to pursue “Unconditional FOCIL”, adhering to many of the design principles of FOCIL, but letting each includer’s list be unconditional. Besides being a viable path to an encrypted mempool as in LUCID, it can also be helpful under a multidimensional fee market as in EIP-7999. Further details and analysis on Unconditional FOCIL besides what is outlined here will be presented separately.

UIL with overflow

The ToB_marginal_ranking_fee_per_gas is removed from the ABB. Each IL is allowed to consume at least ST_gas_min_per_IL of ToB gas, a number calculated as ST_gas_min_per_IL = ToB_gas_limit // IL_COMMITTEE_SIZE. The actual ToB gas the IL can consume depends on how much other ILs consume. The max_bytes_per_inclusion_list can be set such that ILs can fill up calldata up to the ST_gas_min_per_IL, or lower. The order of the ST-commitments, and secondarily, the order of STs within bundles, defines the IL-specified priority order. The builder increases the maximum gas that an IL can consume until the aggregate of all gas_obligation entries exceeds the ToB_gas_limit, and then reduces that maximum to remove the last added transaction. Thus, the (non-deduplicated) aggregate of the gas_obligation entries must be within the ToB_gas_limit, just as previously.

Attesters check that every timely observed ST-commitment has a correctly specified gas_obligation, given the maximum of all gas_obligation entries and the published decrypt bits. Each decryptor also verifies this for their own commitment. They release the key(s) for transactions with decrypt = 1, such that the aggregate of the ST gas limits equals gas_obligation.

UIL without overflow

Under the unconditional IL version without overflow, each IL is capped at ST_gas_limit_per_IL = ToB_gas_limit // IL_COMMITTEE_SIZE of ToB gas. Because this cap is fixed per IL, the gas_obligation field can be omitted from the ABB. Since includers still could equivocate, it seems reasonable to retain the commitment_root in the ABB.

UIL together with UPIL

Another viable design is to let the IL unconditionally include ST_gas_limit_per_IL = ToB_gas_limit // IL_COMMITTEE_SIZE, and let additional transactions instead be included according to UPIL. The overhang is then limited by max_bytes_per_inclusion_list.

4. Distributed payload propagation

The payload relies on references to pre‑gossiped transaction data and prior ST‑commitments, instead of duplicating transaction bytes in the payload broadcast. The consensus representation is extended with st_tickets and decrypted_transactions (Section 4.2), but the regular transactions list remains a list of full transaction bytes as in today’s execution payload. The network representation sent over P2P differs and is used as a transient optimization.

4.1 Network representation

A lightweight payload broadcast is introduced. Besides carrying full transaction bytes for transactions that are not sourced from inclusion lists, the DistributedExecutionPayloadEnvelope also includes a list of pointers to transactions that nodes are expected to already have (or be able to fetch) from canonical ILs. Each ILTransactionPointer also specifies the position of the IL transaction in the block’s final transactions list (the consensus representation).

class ILTransactionPointer(Container):

committee_index: uint8 # 0..IL_COMMITTEE_SIZE-1

tx_index: uint16 # index into the canonical IL body for this committee_index

position: uint32 # index in the final full transactions list

The network representation of the payload does not refer to the STs. The ABB that the builder also produces is sufficient for deterministically reconstructing the ST-tickets and decrypted STs. Specifically, the ST-commitments in the scheduling ABB, with their decrypt bit specified by the builder, identify the ST-tickets that the payload includes and their order. Likewise, the key_adherence bits identify the decrypted STs that should be included, with their order determined by the ToB fee. Further nuances pertaining to recovery are discussed in Section 4.5.

Thus, concretely, the DistributedExecutionPayloadEnvelope mirrors the ExecutionPayload header fields (everything needed to recompute block_hash), but relies on pointers (ILTransactionPointer) for transactions sourced from ILs, and ABBs for reconstructing ST-tickets and decrypted STs.

4.2 Consensus representation

The consensus representation of the execution payload is extended with two additional lists, st_tickets and decrypted_transactions.

st_tickets

The st_tickets is a list of signed ST tickets that are charged at the start of processing the block and correspond to the set of ST commitments that are pending (i.e., have not yet been charged). The builder must include every ST ticket that it sets decrypt=1 for in the ST-commitment of its ABB. Under recovery (Section 4.5), the builder must only include ST tickets corresponding to the pending ST‑commitments in the relevant ancestor ABB with decrypt = 1 that remain after deterministic filtering (dedup, nonce feasibility, chargeability).

The st_tickets list has a canonical order: it is constructed by scanning the scheduling ABB’s IL_data in increasing committee_index, then scanning commits[] in increasing commit_index, and (for bundles) scanning entries in increasing tx_index, and including the ST ticket for each entry that remains after deterministic filtering.

decrypted_transactions

The decrypted_transactions is a list of decrypted ToB transactions executed ToB in the current block. Each entry contains (ticket_index, plaintext_tx, ToB_fee_per_gas), where ticket_index is an index into the st_tickets of the block that scheduled the transactions currently being decrypted (normally, the previous block). The ticket_index is included as a lightweight pointer when processing the block, and a block is invalid if the same ticket_index appears more than once in decrypted_transactions. Whenever two sets of st_tickets (Section 4.5) point to the same decrypted_transactions list, the ticket_index is numbered such that the later of the st_tickets are indexed starting at len(st_tickets).

The entry is valid only if hash_tree_root(RevealCommitmentPreimage(t.from, t.nonce, plaintext_tx, ToB_fee_per_gas)) == t.reveal_commitment for t = st_tickets[ticket_index]. The ToB ordering must be by decreasing ToB_fee_per_gas, tie-breaking by ticket_index, skipping entries that are not executable due to nonce order when reached.

Properties of the consensus representation

The regular transactions list remains a list of full transaction bytes as in today’s execution payload format. The beacon block includes a SignedExecutionPayloadBid that commits to the full payload, in particular via its block_hash as in EIP-7732. The pointer-based payload format is only used as an ephemeral networking optimization: nodes reconstruct the full ExecutionPayload locally, compute/verify the resulting block_hash against the committed header, and then the execution layer client executes and stores the full transaction data as usual. Syncing operates on full blocks; pointers never become part of the consensus object.

4.3 IL root commitment in the ABB to protect against equivocations

An includer could propagate multiple ILs around the time that the block is built. The builder may only observe one of these ILs before committing to a payload, and decide to include transactions from that IL. There is a risk that nodes on the network instead observe a different IL from the includer, introducing ambiguity about which IL the builder referenced. Therefore, the builder defines the unique “canonical” IL from each includer by including a 32-byte SSZ IL_root for each one in the ABB. Specifically, if the distributed payload references any transaction from committee member i via ILTransactionPointer(committee_index=i, ...), then the ABB included in the beacon block must include a non-empty IL_root for i.

If the builder has not observed an IL from an includer, it leaves that entire entry empty. It is free to include the root of observed ILs that it will not reference in its block, if it wishes to obfuscate the content of the payload before reveal, but can also omit to do so.

Nodes are instructed to always forward the canonical IL also under equivocation (together with one additional IL to indicate that equivocation). If nodes have already forwarded two ILs from the same includer and learn that a third IL is canonical, they also forward the third IL when receiving it. The builder re-seeds its canonical ILs after the publication of the bid if it observes an equivocation. It remains possible to penalize includers for equivocations, and seems more relevant to do so under DPP, given the increased importance of the DA of the ILs.

4.4 Payload reconstruction

The complexity is encapsulated within the CL client. The workflow is as follows:

- IL reception: The CL client receives ILs via P2P and stores them in a local cache keyed by

IL_root. - Payload reception: It receives the

SignedDistributedExecutionPayloadEnvelope, verifies the builder signature, and checks that its(slot, beacon_block_root, builder_index, block_hash)matches theSignedExecutionPayloadBidcommitted in the beacon block. - Resolution and reconstruction:

- The client resolves all

ILTransactionPointerentries by looking up the canonicalIL_rootforcommittee_indexfrom the ABB in the beacon block, fetching that IL from its cache (requesting it if missing), and reading the full transaction attx_index. It merges these transactions with the envelope’s fulltransactionsby inserting each IL transaction at its uniquepositionin the final list. - The client constructs

st_ticketsdeterministically from the scheduling ABB (normally, the current slot’s ABB; under recovery, the uncharged ancestor ABB). It scansIL_data→commits[]->(bundletx_index) in canonical order, applies the deterministic filtering rules (dedup, nonce feasibility, chargeability), fetches the correspondingSealedTransactionbytes, and extracts the ST ticket for each remaining entry. - The client constructs and orders the

decrypted_transactionsdeterministically from the ST commitments whose decryptions are due for this block: in normal operation these are the parent block’s scheduled ST commitments; under recovery this may include commitments due from both the most recent full ancestor and the first empty block (Section 4.5). For each such commitment that has a valid released key message which the ABB adheres to, it decrypts to obtainRevealedTransaction(plaintext_tx, ToB_fee_per_gas), identifies the corresponding charged tickett, and verifies:hash_tree_root(RevealCommitmentPreimage(t.from, t.nonce, plaintext_tx, ToB_fee_per_gas)) == t.reveal_commitment. It then creates adecrypted_transactionsentry that includes theticket_indexoftinst_tickets. Finally, it orders by decreasingToB_fee_per_gas, tie-breaking byticket_index, and applies the per-transaction payability check in that order (dropping any entry that fails it).

- The client resolves all

- Verification: The client computes the resulting

block_hashand verifies it against theSignedExecutionPayloadBidin the beacon block. - Execution: The client passes the fully formed

ExecutionPayloadto the engine API (engine_newPayload). - PTC vote: Nodes keep fetching missing ILs/ST bytes/keys and retry reconstruction as new data arrives. PTC members vote “timely” at T_4 only if they have fully reconstructed the payload and verified

block_hashby then; otherwise they vote “not timely”.

4.5 Recovery under rejected payload

Senders have the right to get their decrypted transactions included in the next block if the ABB of the beacon block specified a correct gas_obligation entry for their ST-commitment, the aggregate of all gas_obligation entries is within the ToB_gas_limit, and their ST-commitment and decryption key(s) are available. However, payload n may be rejected, by no fault of the sender or decryptor, after the decryption keys are released. In this scenario, the next payload must include both the decrypted STs that were scheduled for payload n and the STs with keys released in slot n, that were scheduled for n+1.

Concretely, the decrypted STs of a block are the STs that:

- have ST bytes and keys available,

- were listed in a correctly specified ABB, where that ABB

- is not the ABB of the current slot,

- has not yet had its decrypted ST-commitments included onchain.

Thus, when a block is empty (no payload), the next payload must include the decrypted STs that the empty block should have included, as well as the (now decrypted) STs that the empty block committed to in the ABB. The recovery payload can then not commit to new STs (as suggested by Potuz here), but must instead indicate whether the ST commitments of the empty block are currently available (byte+keys), using the key_adherence bit. These bits also flag for the ST tickets, that must under recovery go into the same payload as the decrypted STs. If the block fails to include the decrypted STs such that the chain recovers, it must also be voted as empty, and the duty to recover again falls upon the next payload.

In the baseline specification, decrypted STs are allotted at most 1/4 of the gas limit. This ensures that when a payload is missed, the next one can include two sets of decrypted STs, which at most consume 1/2 of the block’s gas limit.

5. Reveal optionality in LUCID

A possible concern under a sealed transactions commit–reveal scheme is the reveal optionality. Some STs will be used to “backrun”, e.g., changes in CEX prices since the previous block. The decryptor will only reveal in the case that the CEX price moved in the right direction, such that the PT’s trade on the DEX is profitable. However, senders that do not exercise their option still pay the full gas limit for their transaction, the transaction content is never executed and does not count against the gas limit of the block where it was to be included, and its body (encrypted_tx) does not become part of chain history (consensus representation). Thus, senders that seek optionality hardly burden the protocol. Furthermore, since STs can only enter the protocol’s view via ILs, it is possible to enforce timing constraints on the STs, as will be discussed in Sections 5.2-3.

Note also that LUCID prevents probabilistic sandwich attacks, where an attacker could try to guess what a sender will do in their transaction, based on, e.g., specific tokens that it holds. The sender account can remain hidden until reveal-time, since the sender of the ST does not need to be the same account as the sender of the PT. This section will review various aspects of reveal optionality in LUCID, including how it is designed to be prevented, as well as possible extensions that can be made to further alleviate any potential concerns.

5.1 Limited scope of the network representation

Sealed transactions that are not executed pay the full fee, while having resource consumption limited to the network representation. Consider what happens when the sender decides for or against exercising their “ST option”:

- In the case that the CEX price moved in the right direction, the decryptor can release the key so that the transaction executes. Its paid base fee, ranking fee, and ToB fee are then burned.

- In the case that the CEX price does not move in the right direction, the decryptor can withhold the key such that the

plaintext_txis not revealed. The ST ticket will in this scenario already have been charged when processing block n. The transaction will not execute in block n+1 and will not consume execution gas in that block. The ciphertext body (encrypted_tx) also never enters the consensus payload: it is only gossiped off-chain (via ILs and/or independently P2P). Onchain, the footprint is the ST-commitment (in the ABB) and the charged ticket inst_tickets(there is nodecrypted_transactionsentry). Thus, the ST consumes very little resources and pays in full for resources it did not consume. This payment is burned. In essence, LUCID therefore burns MEV associated with arbitrage/backrunning via STs that are not executed; a form of probabilistic MEV burn.

5.2 Builder-advantage at time of commitment

A sender can rely on the builder of slot n to have its ST-ticket inserted even when submitting after the IL observation deadline. These senders thus gain an advantage over senders that must adhere to the deadline to guarantee inclusion (h/t Julian Ma). The timing advantage pertains to probabilistic arbitrage. Since the PT committed to before or at the start of slot n will only be executed in block n+1, the sender cannot backrun/arbitrage value known to the builder of block n, or value already set to be backrun by an ST committed to in block n-1 and executed in block n. The sender can instead construct an option with a slightly higher expected value, which then may be exercised one slot later. Further note that the builder of block n may wish to play it safe by adhering to ILs that it first observes also after the observation deadline.

The builder also confers another advantage—it knows the content of block n at the time that STs are committed for block n+1. It knows exactly which arbitrage opportunities that are executed in the payload, and which keys it has deemed timely. Due to the advantage both pertaining to time and knowledge, we may suspect that some STs committed to in slot n that are focused on probabilistic arbitrage will enter via the builder in one form or another, turning these STs into an extension of block n. If this is deemed too problematic, two options can be considered:

- It is possible to enforce a unified deadline, either via the PTC or in other ways. Such designs are currently worked on with Julian and options are studied.

- It is possible to extract a fee for ST-commitments that are not revealed. Such a design is presented in Section 5.4.

5.3 Builder-advantage at time of key release

The view-merge mechanism could also confer the builder of block n+1 an advantage at the time of key release—the builder can allow senders to determine if they wish to exercise their option after the key observation deadline. Thus, if a sender derives a benefit from observing other decrypted transactions before releasing their keys, or by waiting until after the deadline to release the key, they may do so after paying the builder for such services. For this reason, the PTC can vote on key timeliness as described in Section 3.8. This produces a single deadline that all decryptors must adhere to.

Of course, some of the benefits derived by observing other transactions may also be derived by conditioning the execution of a transaction on the pre-state, e.g., the pre-swap DEX price and liquidity, which could be observed onchain as the first execution step. The main issue is arbitrage transactions seeking to profit from observed CEX price movements between blocks. Since the sender must define the conditioning logic ex-ante, it must do so without knowledge regarding exactly which onchain price-movements that are optimal to condition the trade on.

5.4 Possible fee for failure to reveal

As discussed in Sections 5.2-3, it is possible to constrain the builder, such that it no longer has the last-look advantage over STs. A second option is to instead discourage senders from seeking out reveal optionality at all by assigning a fee for a failure to reveal. The simplest solution is to reserve an additional amount from the sender when charging for the st_ticket. Upon processing the decrypted transaction, the same amount is refunded to the sender.

Since the decryptor and sender can be distinct entities, it would be ideal to minimize trust between the parties. It is only the sender’s fault that an ST could not be decrypted if it was malformed; otherwise it is the decryptor’s fault. If the protocol can determine which of the parties is to blame for a failure to reveal a transaction, it can also properly assign blame. However, it is not trivial cryptographically to let the decryptor prove that it has released the correct key, and this is beyond the scope of this post. A simple option is to always assume that the sender is at fault, as long as the decryptor releases a timely well-formed key. Another option along these lines is to give the sender a window during which it can reveal its ephemeral private key to prove its innocence. If the sender proves its innocence, the fee is taken from the decryptor, and otherwise it is taken from the sender. This would require further additions to the protocol and has the disadvantage that the sender needs to reveal its plaintext to prove innocence.

To penalize a registered decryptor, it should be staked and can only commit to a gas_obligation that is within its bonded capacity. Still, the sender must always be able to take on the role of a decryptor to allow for self-decryption, thus warranting a separate path where the sender is precharged as previously discussed.

Two methods are viable for setting the fee upon failure to reveal:

- The decryptor and/or the sender can specify the fee they are willing to pay (per-gas), and the ordering of the transaction ToB determined by the fee they commit to. This has the benefit of not unnecessarily burdening transactors (perhaps self-decrypting) that simply want to be protected against sandwich attacks from the risk of having to pay a fee upon a technical issue when trying to reveal the keys.

- There can be a minimum fee that every sender must pay upon failure to reveal, to inhibit probabilistic arbitrages, if this is desirable. It is possible to combine (1) with (2), and to keep (2) small. The minimum fee can be set: (A) as a constant, (B) in proportion to the base fee, (C) in proportion to the time-averaged sender/decryptor-specified fee in (1), (D) adjusted automatically based on the (per-gas) time-averaged reveal failure rate and possibly the

ToB_gas_limitusage rate.

In (1), the sender has an incentive to commit to a high fee to be ordered ToB. It is therefore reasonable to combine the fee that the decryptor commits to and the fee that the sender can commit to (using the already established self-decryption path) when ordering transactions. Likewise, if a decryptor in (2) has the ability to set the max fee under which it is willing to be assigned new STs, senders will want to have the ability to increase that fee (in order to exceed the protocol minimum fee) using the same path.

It can be noted that once it is possible to assign blame between the decryptor and sender, it is also possible to improve the decryptor_fee accounting. Specifically, the protocol could still charge senders and burn the decryptor_fee under a failure to reveal if the sender is at fault.

6. Discussion

6.1 Modularity and roadmap

LUCID is an extensive upgrade but the components described in this post are modular. There are multiple viable adoption paths depending on which objective is prioritized first.

General direction

Among proposals of this post, the only core dependency is that the staggered inclusion lists in Appendix A should be adopted after UIL/UPIL. Otherwise, builders will increasingly stuff the block to remove transactions surfaced by timely includers. It seems reasonable to adopt the encrypted mempool before making the payload propagate in a distributed manner. Note that the design would still not force the consensus representation to carry transactions that failed to decrypt. The builder will simply omit transactions from the payload when their keys were not timely revealed. Thus the guarantees discussed in Section 5 still hold: unencrypted transactions do not become part of chain history, the senders still pay the full gas limit, the transaction content is never executed, and its gas does not count against the gas limit of the block where it was to be included.

Minimum viable EIP

A minimum viable EIP of LUCID would omit DPP (certainly for regular transactions), UPIL, SILs and potentially bundles.

Applying UIL without overflow (Section 3.10) still seems viable, and would make for a clean separation between STs and regular transactions. The STs do not compete for the same blockspace since the ToB_gas_limit applies to the next block. Each IL will thus have an allotment of ST_gas_limit_per_IL = ToB_gas_limit // IL_COMMITTEE_SIZE, and can at most include MAX_COMMITS_PER_IL ST-commitments, which should be kept moderate initially, e.g., 4. Each IL is limited in terms of byte size as normal. The regular post-execution check of FOCIL will not need to concern itself with STs and works as currently specified.

Even if the builder of block n+1 will propagate the full consensus representation in the payload, it is still useful to be able to promptly propagate STs efficiently after they have been committed to in beacon block n, such that they reach the next builder. If the IL path is to be used for propagating these STs, nodes need to determine the canonical IL under equivocation. Therefore, including the IL_root in the ABB makes sense. Technically, the ST-commitments themselves can be sufficient, but adding the IL_root does not increase the size substantially.

While bundles are very useful, they are not critical for the first phase. Setting MAX_COMMITS_PER_IL=4 would produce 64 STs per block under 16 ILs, which is already a rather substantial allotment. In a design without bundles, the ToB_gas_limit can be a constant set rather moderately, since decryptors will not be able to readily scale up by building bigger bundles.

Thus, the design can be simplified for a first EIP implementation, while retaining the core properties. Given that the cryptography design is open, it is likely that the simple trustless self-decryption ux-flow will dominate initially, before decryptors employing other mechanisms (e.g., threshold decryption or trustful decryption) become established.

6.2 Scaling via DPP

With distributed payloads, transactions included via ILs consume significantly less “instant bandwidth” at the critical moment of the builder’s reveal compared to standard transactions. This distinction allows for a theoretical “envelope allotment” where the byte-size of the DistributedExecutionPayloadEnvelope is capped separately from the gas limit. This could incentivize the inclusion of transactions via the pre-gossiped inclusion list path, or potentially justify a higher gas price for non-inclusion-list transactions that consume the scarcer resource of immediate propagation bandwidth.

Under any ePBS specification, there exists an optimal PTC payload deadline under which scaling is maximized, as exemplified by the equation for \text{PTC}_P^* presented here. This deadline must balance the need for propagating the payload and executing it. Researchers developing ePBS have therefore considered using a deadline for payload timeliness that varies with the amount of calldata in the block. A bigger payload consuming more calldata is allowed longer time for propagation, because it will execute faster. Conversely, a smaller payload must arrive early, so that the proposer of the next block has sufficient time to execute.

This variable PTC deadline could also be used for scaling under DPP. Payloads relying on IL references are smaller, and can thus have an earlier PTC deadline. Consequently, they have a longer execution window. The gas limit can thus be increased in such a way that payloads relying on DPP, with their early PTC deadline, can consume more gas than previously possible. It should however be remembered that the transactions still have to be propagated. The difference is that they can be propagated over a longer time period. In terms of scaling, it can also be noted that nodes could potentially start executing the decrypted ToB transactions already upon reviewing the key_adherence field, since their ordering is deterministically determined by the ToB fee (or the fee discussed in Section 5.4).

6.3 Charging STs under subjective criteria

Encrypted mempools that rely on timely key release necessarily introduce subjective enforcement surfaces: transactions can be charged without executing even when the sender did nothing wrong, if the attesters and builder conspire to ignore timely released keys. This is noteworthy since senders relying on the encrypted mempool no longer have the stronger validity guarantees for their transactions.

Relatedly, the bundle_root committed in the ABB may not be sufficient to objectively verify (from onchain data alone) that a particular charged ticket was a member of the committed bundle, because some entries of the bundle may not become part of the consensus representation (decrypt=0). However, since timeliness by itself is subjective, the bundle_root is strictly used for allowing the decryptor to release its keys directly upon observing the beacon block, instead of having to wait for the payload. Bundles could also have included a scheduled_root over ticket_root entries with decrypt=1. This would prove that the ST tickets included in the payload indeed were scheduled in the ABB. However, due to the otherwise subjective nature of the timeliness check, where the sender needs to trust the builder and attesters anyway, it is not clear that this would improve the design.

Appendix A – Staggered inclusion lists

A.1 Overview

LUCID gives includers meaningful control over block content. It is therefore prudent to specify a compensation model for this role. There is otherwise a risk (as is true for any IL design) that protocol participants fall back to out-of-protocol inclusion fees, which may become a centralization vector. The in-protocol rewards option proposed here is Staggered inclusion lists (SIL), where each IL has a slightly shifted deadline, and the IL with an earliest deadline is rewarded when several ILs surface the same transaction. The temporal distribution incentivizes broad coverage and immediate transaction inclusion.

A.2 Previous designs

A baseline approach is an individual distribution where all includers that surface a transaction share the reward it posts. However, this leads to needless networking overhead, as includers will tend to surface the same transaction if it pays enough. Various other approaches were discussed here, such as:

- A collective distribution to all includers, regardless of whether they surfaced the ST. This approach has the benefit of leading to broad coverage. However, it is not particularly fair and incentive compatible, given that includers are rewarded equally regardless of their contribution.

- A waterfall distribution, where includers are assigned to certain transactions via the transaction hash, and rewarded according to the assigned priority order. However, includers do not have an incentive to communicate beforehand which transactions they will select, and the same issues as under the baseline approach reappear, just in a more complex setting.

- A keyed distribution, where the sender links the reward to a validator ID (or several registered under some collective ID). This allows senders to use in-protocol rewards while having the ability to direct them to any includer they may wish to prioritize.

A.3 Redirecting the priority fee

When an includer surfaces a transaction in UPIL or UIL, the priority fee serves less of a purpose. For STs, ToB ordering is determined by the ToB_fee, and inclusion in full ToBs is determined by the ToB_marginal_ranking_fee_per_gas. Regular transactions can be ordered by the builder, and the builder may still prefer to put transactions paying a higher priority fee earlier to motivate senders to pay high fees. However, the priority fee does not determine whether a transaction is included; inclusion is determined by the marginal_ranking_fee_per_gas (UPIL) or by the UIL rule that the transaction must be unconditionally included. For this reason, it may seem viable to redirect the priority fee to includers when they surfaced a transaction, instead of introducing a new includer_fee. However, one nuance here is that SILs only allow includers to offer “inclusion preconfirmations”, whereas the proposer under a short window after keys have been revealed can offer “execution preconfirmations”. The following text will refer to the “includer fee”, leaving it open whether it is the redirected priority fee when a transaction was surfaced by an IL, or a dedicated includer fee.

A.4 Staggered inclusion list design

The DPP in Section 4 increases network efficiency. However, it does not resolve the inefficiency of several ILs propagating the same transactions. It can be expected that they will do so, particularly if all includers share in the rewards provided by the transactions. It is desirable to come up with an in-protocol solution that decreases the overlap, to achieve broad coverage, while at the same time rewarding includers for their work. It turns out that there is a specific solution that fulfills both objectives, while also providing a form of decentralized pre-confirmations: Staggered inclusion lists (SIL).

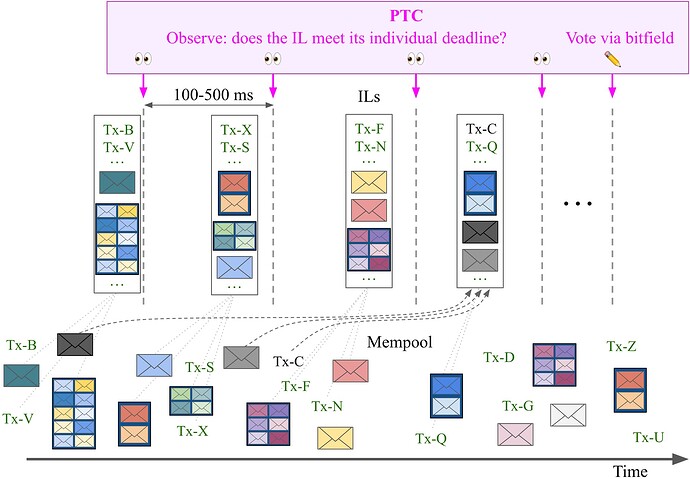

The design is illustrated in Figure 2. Includers are assigned staggered deadlines during the slot. If two ILs both have propagated the same transaction, the IL with the earlier deadline is rewarded the full includer fee paid by the sender. Thus, as the slot progresses, includers iteratively build the payload, but have no incentive to reinclude transactions that have already been propagated. Staggered inclusion lists can be understood as a temporal waterfall distribution scheme—instead of assigning includers to different transactions, they are assigned different deadlines. The prospect of staggering block sharded proposers was discussed during early days of Ethereum (1, 2, 3).

Figure 2. Staggered inclusion list design. The PTC observes staggered deadlines for the ILs and ultimately votes on their timeliness. Includers quickly detect censorship and include new transactions emerging in the mempool. The ST in black is censored three separate times before the fourth IL picks it up.

As an example, a 6-second slot may be divided between 8 includers such that there is a 0.5s delay between each one. The first IL deadline is 0.5s into the slot, and the last deadline is 4s into the slot, leaving some room for propagating votes on timeliness. The deadline order is set in randomized fashion, e.g., by committee_index. The design seems appealing to senders—they will often get near-immediate trustless inclusion in an IL due to the staggered deadlines. Given the strong guarantees of UPIL and UIL suggested in this post, they can thus be fairly certain of inclusion right away, a form of trustless inclusion preconfirmation.

Once the deadline for the last includer has passed, members of the PTC (or, if it runs separately, a better name would be the inclusion list timeliness committee, ILTC) that have observed incoming ILs cast a vote on timeliness by propagating a bitfield of length IL_COMMITTEE_SIZE. In the bitfield, each PTC member declares for each IL whether it met its individual deadline, according to the member’s local view. The builder of the next slot must adhere to all ILs that arrive before the attesters freeze their view, even if they arrive after their individual PTC deadline, but rewards are distributed according to the votes of the PTC.

The builder collects PTC votes and includes them in the block to determine includer rewards, under observation of attesters. Any IL gathering more than, e.g., 1/3 of the vote in favor of timeliness gets the includer fee from the transactions it propagated, as long as no IL with earlier deadline that also gathered over 1/3 of the vote propagated the same transaction. In the case that a transaction is not claimed by any IL that meets the 1/3 threshold, the includer fee is awarded to the builder.

A.5 Timing

It can be noted that a well-connected includer will have an advantage; as will includers in geographic locations where more transactions are initiated. These includers can post their IL a little closer to their deadline, and see transactions on average a little earlier. On the other hand, includers will tend to see transactions propagated from their own region the earliest, even if that region generally initiates fewer transactions. Assuming that the distribution of validators and senders co-vary, competition for including public orderflow will tend to be more fierce in regions that also initiate more transactions. This does not fully neutralize advantages of certain geographic locations, but at least tempers it.

In either case, having validators located closer to transactors is arguably a benefit overall. The time \Delta between deadlines for consecutive includers will impact what effect geographic location has on the distribution of includer fees between validators. Another aspect here is whether ILs have enough space to include all transactions that are available at a given time. It is possible to combine SILs with keyed distribution. This can be valuable for includers relying on private orderflow, where senders submit STs directly to specific includers and wish to compensate them without dilution. These includers will then not need to worry about being “front-run” by a well-connected competing includer.

A not-so-well-connected includer with deadline d+\Delta might post their ILs with some larger margin \delta before the deadline, setting the release d+\Delta - \delta so that the IL can propagate before d+\Delta. If \delta > \Delta, a well-connected includer with deadline d could observe the IL and propagate its own IL using several nodes located at various important points in the P2P graph, to make its own earlier deadline. It seems reasonable to tune \Delta in consideration of reasonable \delta, to avoid such back-running, if keyed distribution is not incorporated.

A.6 Censorship resistance

Staggered inclusion lists improve censorship resistance (CR). Validators make inclusion decisions knowing the decisions of earlier validators of the same slot, and communicate their own decision to later validators. This improves the level of CR provided, both by includers that maximize rewards, and by includers that wish to surface censored transactions to maximize CR:

- A validator strictly focused on maximizing rewards has the option to either censor a transaction or to gain the full includer fee. The bribe required for bribing such an includer is higher than when the includer fee is shared among includers, or when there is uncertainty regarding whom the fee will be distributed to. When the includer does not know beforehand how other includers will act, the expected fee will always be lower than the posted fee, and the required bribe thus lower.

- A validator strictly focused on surfacing censored transactions gains knowledge around which transactions that are censored from observing other includers ignoring a transaction in the mempool. When the includer does not know beforehand how other includers will act by the end of the slot, some transactions will be surfaced by many includers, and some not surfaced at all, simply due to random chance. When an includer observes staggered ILs, it can pick up on censorship immediately, to surface the censored transaction. Simplifying a bit, this moves inclusion times under validators that focus on stopping censorship down from roughly 2-3 slots (e.g., 12s-36s depending on slot time) to 2-3 \Delta (i.e., 0.5s-1.5s depending on the setting for \Delta).

Appendix B – LUCID with tight schedule

B.1 Overview

A benefit of including batch roots in the ABB is the long window for releasing the decryption key. This can be particularly appealing to senders relying on a trustless design if they are not well-connected, or threshold decryption schemes with communication overhead. An alternative specification instead does not rely on the ABB. All decryptors observe included encrypted transactions directly in the payload.

The decryption keys must then be released during a shorter window between the payload deadline and the deadline for the keys. This design has the benefit of more lightweight ABBs containing only IL roots, to facilitate DPP. If DPP is also omitted, the ABB is not required. An early payload released right after T_3 enables the decryptor to release its keys right away and is not a concern. The complicated part is how to deal with payloads that arrive late, around T_4. The decryptor must be able to release keys quickly, but will need to do so while having insufficient information regarding if the payload will become canonical.

The key insight is that the payload can be treated as a special IL for STs that the builder of slot n+1 must adhere to, even if the PTC votes against it. This way, the decryptor gets some margin when making its decision on whether it wants to release or withhold the keys. There are two ways this can be done:

- The decryptor relies on the timing of the release. Should the payload be sufficiently early to be guaranteed to reach attesters before the IL deadline at T_5, it can always release its decryption keys, regardless of whether the payload will reach a sufficient proportion of the PTC by the payload deadline (because the payload will then become an unconditional IL).

- The PTC can vote on payload timeliness as early as possible (before voting on blob timeliness). The decryptor can count PTC votes and be given some additional margin in its release decision, such that late votes cannot sway the decryptor into releasing keys for an ST that does not become canonical, or withholding keys for an ST that is accepted in a valid block.

These two options will now be further examined.

B.2 Payload IL status determined by timing

Upon observing the payload, the decryptor confirms that it matches the hash committed to in the beacon block and is formatted correctly. It has further observed that the beacon block has accrued sufficient attestations. If the payload fails to become canonical but reaches attesters by the time they freeze their view at T_5, it will be treated as a special IL. All STs in the payload must be included ToB by the builder of block n+1, if the corresponding decryption keys also reached attesters by T_5. If a decryption key did not reach attesters by the time they froze their view, the builder is free to ignore the corresponding ST. It is only when the payload becomes canonical and the decryptor did not release the keys by T_5 that the builder of block n+1 can ignore keys for STs that still need to pay for consumed gas (according to the gas_limit).

Decryptors thus have the option to either release or withhold keys for payloads arriving between T_4 and T_5. Builders may wish to play it safe by adhering also to keys arriving after T_5, to ensure their block becomes canonical. This gives decryptors some additional probabilistic margin on key release timing (which is not guaranteed).

Should the payload be sufficiently early to be guaranteed to reach attesters before T_5, it can always release its decryption keys, regardless of whether it will reach a sufficient proportion of the PTC by T_4.

B.3 Payload IL status determined by counting PTC votes

The PTC casts votes on payload timeliness as early as possible, before it also votes on blob timeliness. The decryptor collects votes to determine if the payload will be deemed timely. It is given some margin of error in its decision, within which it can decide to either release or not release its keys. It seems desirable to restrict the optionality to one outcome, such that the decryptor either must release the keys whenever the payload is deemed timely, or must withhold keys whenever the payload is untimely. With this setup in mind, if a threshold of 50% is required for the payload to be deemed timely, the decryptor can be given an optionality between for example, 30%-50% or between 50%-70%.

In the first case (optionality in the range 30%-50%), the decryptor must release keys whenever the payload is timely. Should keys not be released, STs are charged in full according to their gas_limit anyway. Should between 30%-50% of the PTC vote in favor of the payload, it acts as a special IL. The STs it contains must be included decrypted ToB in the next payload, if the keys were available at the attester freeze deadline of T_5.

In the second case (optionality in the range 50%-70%), the decryptor must withhold keys whenever the payload is untimely. Should keys be released when less than 50% of the PTC votes in favor of the payload, someone can front-run the decrypted transaction. Should between 50%-70% of the PTC vote in favor of the payload, STs with missing keys are not charged, and STs with provided keys are included ToB in block n+1 as normally.

Appendix C – KEM‑DEM hybrid encryption