Thanks to Vitalik Buterin, Caspar Schwarz-Schilling and Ansgar Dietrich for feedback.

1. Introduction

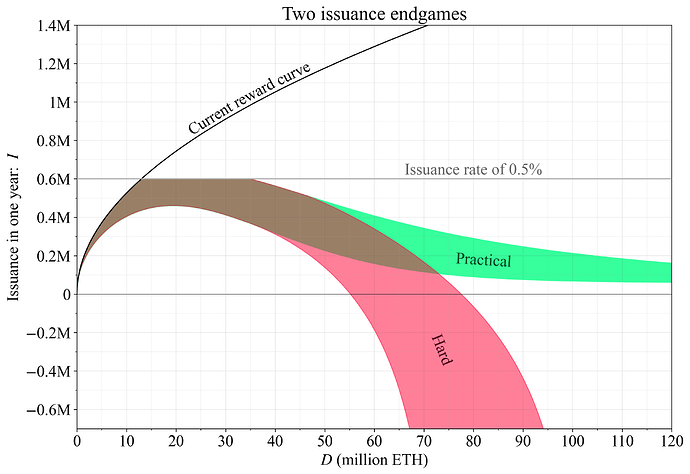

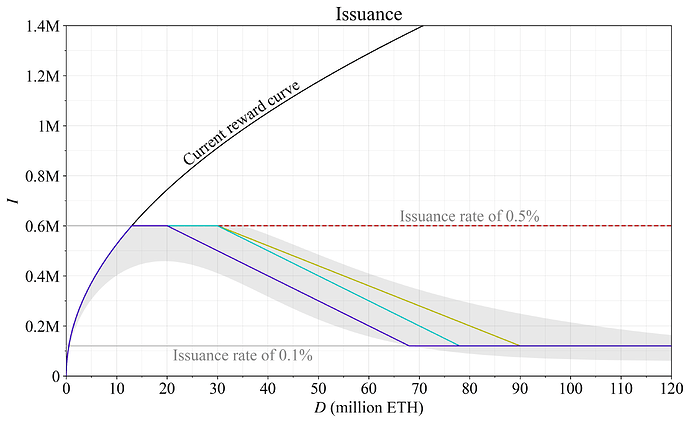

This post presents a practical endgame on issuance policy that can stop the growth in stake while guaranteeing proper consensus incentives and providing positive regular rewards to diligent small solo stakers. Two possible ranges for an endgame reward curve are outlined in Figure 1. A hard endgame (red) with a reward curve that caps the quantity of stake by bringing the yield down to negative infinity comes at the cost of analytical, implementational, and political complexity (a hard cap can be hard to implement). Even setting the issuance yield to zero introduces additional complexities that would be advantageous to avoid if possible—particularly if there is no MEV burn mechanism in place, such that the 0% issuance yield merely halts regular rewards, while irregular rewards continue. Certainty can be the enemy of viability, because bringing down the staking yield to a low yet positive level will, in all likelihood, suffice. This post emphasizes viability: a practical endgame (green) with probabilistic guarantees on the quantity of stake that could be implemented at present.

Figure 1. Issuance ranges for two endgames: a practical endgame in green which can be viable for the near term and easier to come to an agreement on, and a hard endgame in red with higher analytical and political complexity that may push solo stakers into receiving a negative regular yield. Both endgames overlap at low stake deposit sizes (D) and are therefore likely to lead to a similar equilibrium outcome, given reasonable assumptions about the willingness to supply stake at different staking yields.

The great news is that we can offer more stringent guarantees on the maximum proportion of the circulating supply issued each year, regardless of which exact endgame policy that is pursued. To Ethereum’s users, a stringent cap on issuance of native ETH tokens is desirable, because it caps the inflation rate. Since revenue of the protocol can be burned, as partially done today, the ETH inflation rate can be sustainably negative (deflation). Ethereum can have trustless sound money with preserved economic security—something that is very valuable for a decentralized economy. A social cap can be set at an issuance rate of i=0.5\%, illustrated by a grey line in Figure 1. This is an easy-to-understand concept to commit to (memetic qualities), sufficiently high to ensure a viable staking set with ample room for consensus and consolidation incentives, and permits flexibility to temper the quantity of stake as the community sees fit.

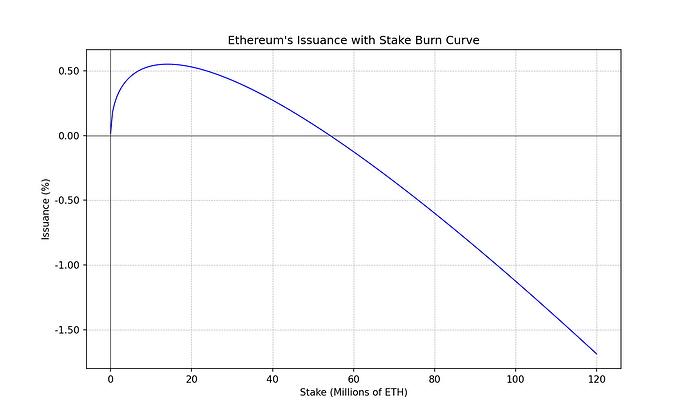

What remains for a potential practical endgame is to come to an agreement on the exact specification of the reward curve and to outline how relevant micro incentives should be designed under it. The curve should approximately follow the shape of the reward curve with tempered issuance. However, a slightly higher yield at lower quantities of stake and a slightly lower yield at higher quantities of stake seems preferable, if the goal is a practical endgame through one singular change in issuance policy. A few options along these lines are suggested, peaking at a 0.5% issuance rate. A cubed reward curve (red in Figure 3) can be highlighted as fitting within the preferable range, but others (e.g., purple and orange in Figure 3) should also be considered. There is an option to simply set the issuance rate to 0.5% for now (dashed in Figure 9) and revisit the issue again in a few years, but this seems harder to find community support for. The post concludes with a set of open questions that the community and researchers should weigh in on.

2. Recap on issuance reduction

First a short recap on issuance policy and the prospect of reducing issuance; for a deeper understanding, read the FAQ.

2.1 Motivation

Currently, around 35M ETH is staked, arguably already more than required, and the quantity of stake is slowly growing in line with diminishing costs of staking and on account of staking frictions being overcome. There are two fundamental reasons to reduce issuance:

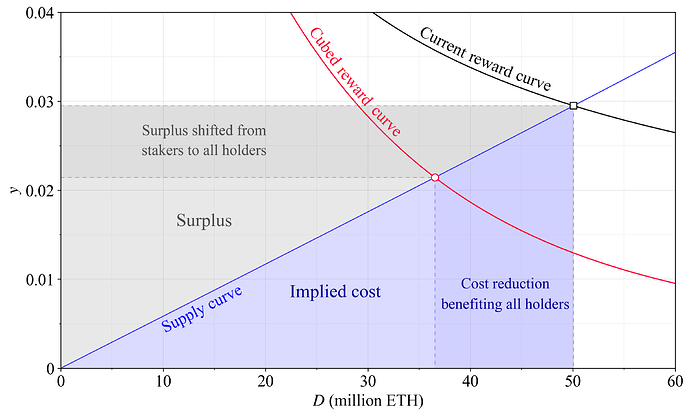

- The current reward curve compels users to incur higher costs than necessary for securing Ethereum (costs broadly defined to include hardware, risks, illiquidity, taxes, etc.). Reducing issuance improves welfare by lowering these costs in aggregate, as illustrated in the FAQ in Figure 1 and Figure 26.

- It is valuable to have trustless sound money as the primary currency in a decentralized economy. High issuance can lead a liquid staking token (LST) to dominate as money. Lower issuance ensures that app developers and users will not be subjected to monopolistic pressure from LST issuers, or needlessly risk the LST failing, potentially even threatening consensus if an LST becomes “too big to fail”.

2.2 Impact

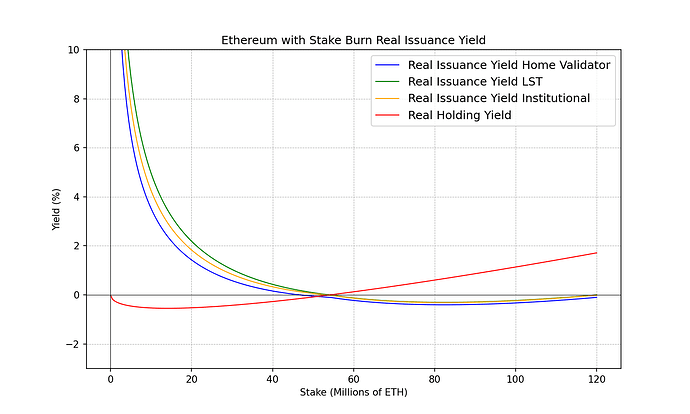

When discussing issuance and contemplating the effect on stakers, it is important to remember that the stake supply curve is upward sloping. Therefore, when the yield is reduced, the equilibrium yield will only fall by a fraction of the nominal reduction (see Figure 2 in this post). Furthermore, what matters to the staker is the proportion of all ETH they attain. Higher issuance dilutes also stakers, and if some stakers leave, remaining stakers may gain a higher proportion of the total ETH, in accordance with the equations in the post on minimum viable issuance (MVI). This change in the attained proportion of the total ETH has also been referred to as “real yield”. The effect can be illustrated using an isoproportion map, with 1D examples also available (1, 2). Another way to illustrate this is presented in the thread on MVI, which, in a single plot, tries to capture how reduced issuance can increase welfare (all groups are better off), increase the attained proportion of all ETH among stakers, and produce a moderated fall in nominal yield under equilibrium.

Endogenous and exogenous yield

It is important to understand the difference between:

- endogenous yield, constituting rewards derived from staked participation in the consensus process, such as issuance, MEV, the sale of preconfirmations—and even staking airdrops; and

- exogenous yield, constituting rewards derived outside of consensus participation, such as in DeFi in the form of for example restaking yield.

Early in the debate, there was concern that, e.g., restaking would make solo staking impossible under an equilibrium enforced at a lower quantity of stake. The motivation was that delegating stakers are better equipped to derive exogenous yield. While there are some merits to the general concern, exogenous yield can also be derived directly from non-staked ETH. Thus, if the endogenous yield approaches zero, there will be no incentives to stake for anyone—not for solo stakers and certainly not for delegating stakers—other than to protect or attack Ethereum.

2.3 Downsides

However, an issuance reduction may not only bring benefits. A concern is that solo stakers are more sensitive to a reduction in staking yield due to their higher fixed costs (e.g., hardware). It is therefore possible that a reduced issuance will decrease the proportion of solo stakers somewhat (review how differences in reservation yields in Figure 11 could alter the proportion of solo stakers in Figure 13). This is a potential downside that must be balanced against upsides of reducing issuance, but there are also counterarguments pointing in the other direction. It should further be noted that when issuance falls with increased stake participation, the viability of discouragement attacks (1, 2) and cartelization attacks increases.

Furthermore, if issuance is reduced to below the level of the MEV, especially when close to zero or negative, consensus incentives will be negatively affected, and variability in staking yield among stakers who cannot effortlessly pool their MEV rewards (i.e., solo stakers) will increase. For these reasons, a mechanism for burning MEV (e.g., 1, 2, 3, 4, 5) is important to implement—yet such a mechanism may be a long way from adoption. It might also not be possible to burn all MEV if, e.g., proposers and builders can collaborate to keep down the attested MEV (1, 2, 3). However, there are then strong incentives for competing stakers to integrate with builders to make bids that keep the burn at rather high levels.

The lack of consensus incentives at lower issuance can be compensated for by increasing the penalty for missed attestations. Yet if the maximum issuance is zero (i.e., a zero base reward per increment), such relative adjustments are ineffective. A regime of increased attestation penalties will also open up for minority discouragement attacks, wherein the proposer selectively drops attestations to harm competing stakers. If proposer penalties are adapted to compensate, a missed proposal will become rather costly to the offline solo staker, who will already take relatively high losses due to increased attestation penalties. Remedies such as reducing the penalty if the proposer was inactive during the previous 2-4 epochs can then be considered, but design complexity increases.

Consolidation incentives under a transition to Orbit SSF could also be negatively affected by a reduction in issuance. There are good reasons to distribute proposal rights according to stake in Orbit SSF, just as today, at least if there still is MEV to extract. Otherwise, if consolidated validators are premiered, it becomes difficult to retain fairness since the protocol is not aware of the expected MEV revenue. With proposal rights distributed according to stake and low or negative expected attestation revenue, stakers have strong incentives to deconsolidate and reduce their activity rate, since this reduces slashing risks. Increased attestation penalties are then less relevant, since stakers simply can ensure that they are predominantly inactive by running many small validators.

To ensure consolidation, relatively substantial individual incentives must be pursued, at least before a MEV burn mechanism is in place. This means that under very low or zero issuance, small solo stakers would have to lose ETH every epoch while waiting for the chance to propose. In line with the reasoning in Section 2.2, small validators’ expected endogenous yield would still remain positive, but solo stakers that cannot effortlessly pool rewards suffer from the high relative variance in rewards. The more complex option is to assign relatively more block proposals to consolidated stake when the consolidation level is low and no MEV burn is in place.

Collective consolidation incentives would also by definition further reduce issuance from an already low baseline if the validator set is not consolidated, once again potentially pushing the solo staker into negative territory.

3. Practical endgame

3.1 The role of the reward curve

Ethereum’s consensus mechanism relies on a reward curve that stipulates how much ETH that should be rewarded for performing each validator duty when a certain amount of ETH is staked, effectively determining the maximum total issuance under perfect participation. The reward curve should roughly reflect the diminishing marginal utility of adding additional stake once security has solidified. Specifically, it should be designed as the “issuance policy expansion path” that optimally balances relevant trade-offs. It can be understood as a utility maximizing locus of preferred equilibrium points along possible supply curves. In other words, the reward curve should not produce an equilibrium at less desirable points along the supply curve when more desirable equilibria can be achieved. A PID controller guaranteeing some specific quantity of stake is therefore not desirable; it fails to accurately price the marginal utility of additional stake in the long run.

3.2 Endgame categories

Various approaches have been discussed for the issuance endgame; five loosely delineated categories are highlighted in the issuance reduction FAQ.

Category 4 has been referred to as economic capping, targeting, or stake capping, constituting a yield that approaches negative infinity, which was discussed in a recent extensive write-up. The benefit is the absolute guarantee of capping the quantity of stake, even in the presence of MEV. A potential downside of this approach, certainly if the cap is set low, is that the equilibrium yield can become unattractive to solo stakers, particularly if there is no MEV burn to reduce reward variability (as discussed in Section 2.3). Another issue is the additional logic required to facilitate the negative yield (e.g., a staking fee deducted each epoch). Figure 10 in this post shows a realistic scenario with negative regular income for solo stakers under a staking fee. A third downside is that a negative issuance yield can create a “consensus design debt” due to additional analytical and implementational complexity whenever micro incentives are adjusted. Figure 1 outlined the approximate range I see as suitable for a Category 4 design, with the cap reached at around 2/3 or 3/4 of all ETH staked. The figure refers to it as a “hard endgame” due to its complexity and hard cap.

Category 2 instead involves a more modest reduction of issuance. It represents the type of reduction that would be desirable for the near future and does not require incorporating additional logic to maintain proper consensus incentives. It has been proposed as a first step followed by a Category 4 change. A longer write-up on a reward curve with tempered issuance is available here. While it is likely that this type of reward curve could be viable for a long time, a potential downside is the lack of near-certainty.

Category 3 occupies a middle ground between the two approaches, with curves retaining a positive issuance yield being most relevant. Issuance is then cut to a very low level when too much ETH is staked, yet remains positive. While consensus/consolidation incentives and solo staking can become strained, diligent solo stakers will not need to “pay to stake” while waiting to propose a block, and there is lower “consensus design debt”. This constitutes a practical endgame, if the goal is to make one near-term adjustment to issuance that has a high probability of lasting indefinitely. In reality, the difference between Categories 2 and 3 is relatively minor in the sense that they will likely lead to similar equilibrium outcomes. However, it might lend credibility to the notion of aiming for an endgame if the issuance yield at higher quantities of stake is set to a minimum (positive) level.

It has been argued that Ethereum must aim for one single change to its issuance policy, credibly positioned as the last change ever needed. My personal contention is that there are many benefits to a graduated approach. If there was community support to set the reward curve at an issuance rate of 0.5% with a commitment to revisit the issue in a few years’ time, I would support it. It would make the process less complicated in the near term. However, the political nature of an issuance change and community reactions seem to support pursuing the endgame policy through a single change.

Due to the inherent costs of staking and the limited relevance of exogenous yield, a Category 3 change offers a credible case to be the last monetary policy change required. Responsibility then falls on developers to implement MEV burn moving forward. A MEV burn mechanism would: (1) alleviate the strain on consensus design parameters from low issuance at a high quantity of stake, and (2) make a lower equilibrium quantity of stake more likely. Note also that instituting a Category 4 stake cap does not preclude the necessity of future changes. Quantity of stake is not the only factor at play when Ethereum aims to balance issuance policy trade-offs. Indeed, key issues twenty years from now may differ greatly from those in focus today, just as many of the issues we currently face were not anticipated just a few years ago. A stake cap issuance policy could therefore need to be reversed, just like any other policy. In this case, the reversal would more likely be in the form of an increase in issuance, a direction that Ethereum has so far avoided.

3.3 Preferred issuance range for a practical endgame

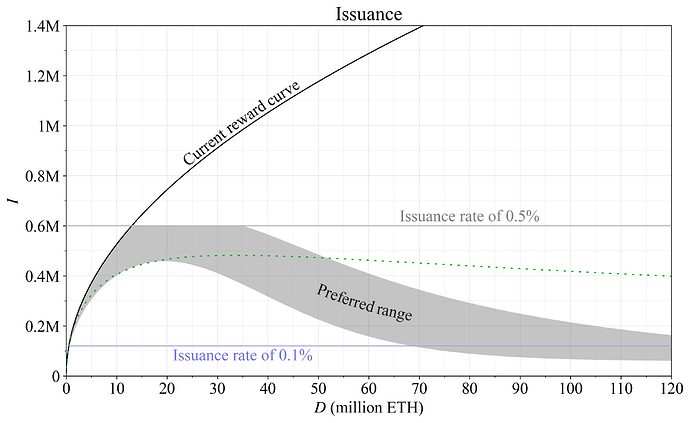

Figure 2 roughly outlines a preferred range for a practical endgame reward curve (previously shown in green in Figure 1). This range represents my personal preferences, given early sketches of consolidation/consensus incentives. Others may have different preferences, which should be collated and further debated. Sketches of the incentives design may also evolve, leading to minor tweaks to the range. The dashed green curve is the previously proposed reward curve with tempered issuance. If the requirement is an endgame, it seems reasonable to go lower than the green curve at higher deposit sizes. The preferred range suggests still issuing at least 60k ETH if everyone stakes (an issuance yield of around 0.05%) and at most 100k ETH more than that (160k ETH). My contention is that the only scenario where an equilibrium is approached at this level is if MEV is much higher than today. The idea is that the last fraction of would-be stakers have relatively very high reservation yields (require a rather high staking yield to stake), which should probabilistically be accounted for. A lower positive issuance might then not influence the equilibrium much anyway, while likely requiring us to push small solo stakers into negative regular rewards in the presence of MEV, something I find undesirable.

Figure 2. Preferred range for issuance across staking deposit size D for a practical endgame issuance policy (personal rough view). The policy should ensure a sufficient issuance yield at low deposit sizes (but not more), and also such a low issuance yield at high deposit sizes that an equilibrium is extremely unlikely. For improved viability, issuance is still maintained at a positive level throughout.

Assume for example that developers are unable to institute MEV burn and that an equilibrium at a high deposit size is reached when MEV is 600k ETH per year (a doubling of the long-run average, which seems perfectly possible). Whether issuance is 0 ETH or 100k ETH will then not alter the equilibrium substantially. Issuance will at least certainly be of less importance to the delegating staker, who effortlessly derives pooled MEV rewards. Yet, if issuance is 0 ETH instead of 100k ETH, this presumably requires a larger redesign of the micro incentives and will force solo stakers to pay to stake, in the hope of getting the chance to propose a block. If MEV burn is instituted, an equilibrium will not be reached here anyway, and an issuance of 100k ETH thus still has little relevance. The upper limit to the preferred range was defined according to the following intuition:

- It can be desirable for Ethereum users to cap the issuance rate at 0.5% (see Section 3.4), producing a maximum 4% issuance yield at 15M ETH staked, 3% at 20M, and 2% at 30M.

- The issuance rate should presumably not remain fixed at 0.5% for an endgame policy due to the diminishing utility of additional security past a certain level. A further reduction starting at the current deposit size (35M ETH) or lower then seems desirable.

- Issuance should not be higher than absolutely necessary at the highest quantity of stake, due to how undesirable such an equilibrium is. Going above 160k ETH (around half of the yearly MEV measured in this post; 0.133% in issuance yield) seems excessive—it should reasonably be possible to design viable consensus/consolidation incentives below that level.

Presumably, the first fraction of stakers have relatively low reservation yields (require a rather low yield to stake), which should also probabilistically be accounted for. However, if the reward curve must remain fixed forever, Ethereum should issue slightly more tokens than what is needed to achieve an equilibrium at a desirable deposit size. The reason is that the MEV might eventually be burned, which must be factored in. With current thinking about desirable deposit sizes, it then seems beneficial to keep issuance at or ideally above the green dashed curve at lower quantities of stake.

A question is then how fast issuance should fall down to some minimum acceptable level as the deposit size increases. My contention here is that it seems reasonable to keep the issuance rate above 0.1% up to at least half the ETH is staked. The reason is that a 0.2% staking yield (0.1% issuance rate at 60M ETH staked, with MEV burn in place) could perhaps become more consequential to Ethereum, for example, in terms of effects on decentralization, than the fact that half the ETH is staked. This is in line with the philosophy outlined in Section 3.1—evaluating the utility of different equilibria along an upward-sloping supply curve. Of course, it is highly unlikely that an equilibrium would be established at such a low yield at 60M ETH staked, but the hypothetical options in that scenario must still be evaluated.

3.4 Tangible framework: never exceed an issuance rate of 0.5%

A practical endgame should ideally position the chosen reward curve within a tangible framework that is easy to understand. The upper grey line in Figures 1 and 2 represents an issuance of 0.5% of the circulating supply each year, i.e., an issuance rate of i=0.005. From a communication perspective, committing to never issuing more than 0.5% of the circulating supply each year is an accessible policy with “memetic” qualities. Taking some liberties, it also fits within the “power-of-two” framework favored in Ethereum: a maximum of 2^{-1}% of the supply. Note that the framework is not only applicable to the practical endgame reward curve; it is intended to apply forever. Even if in the future there is a push for an issuance change, there could still be an existing social commitment, making an increase to the issuance rate above 0.5% particularly difficult to push through. Whereas a cap on the circulating supply is an untenable monetary policy, a cap on issuance rate is not. Yet it has the same simplicity.

The circulating supply will drift to balance supply, demand, and protocol income. Therefore, the pledge would ultimately be enforced by swapping out D for d in the equation for the reward curve and normalizing by including the circulating supply at the time of the swap, once the circulating supply begins to be tracked at the consensus layer.

4. Practical endgame reward curves

This section proposes practical endgame reward curves, also including further analysis of the trade-offs Ethereum faces. Examples will be constructed to peak at i=0.5\%, but this peak can be adjusted if desirable by altering the scale parameter (often denoted k). In particular, the peak of any curve can always be reduced slightly while still remaining below i=0.5\%.

4.1 Classical tempering

Issuance

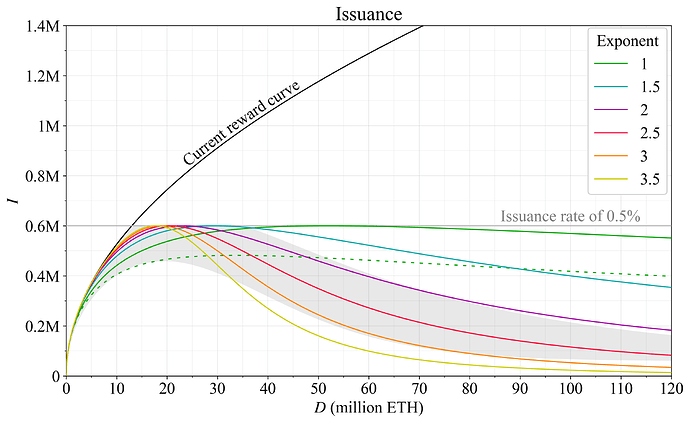

Figure 3 provides examples using the classical tempering mechanism. The particular construction of these reward curves was first motivated by its minimal spec change, as well as ensuring no issuance increase at any point. Note further that the generated smooth decay in issuance is desirable in light of discouragement attacks (1, 2) and cartelization attacks.

Green reward curves are constructed by dividing the equation of the current reward curve by 1+D/k, where k also denotes peak stake participation. The shape of the curve can be altered by exponentiating D, and the peak position (scale) can be altered by changing k. The dashed green curve is the same as presented in Figure 2, whereas the full green curve increases k so that the curve peaks at i=0.5\%, the level marked by the grey line. The curves of other colors in the figure are constructed by increasing the exponentiation in steps of 0.5 up to 3.5 (for the yellow curve), adjusting k to always produce a peak at i=0.5\%. The purple curve is thus constructed through division by 1+(D/k)^2. The peak will then be located at D=k\sqrt{3}, and the variable k was in this case set to 40\times10^6 to produce the peak at i=0.5\%. In Figure 15 of the FAQ, a slightly lower setting for k was instead relied upon for the purple curve.

Figure 3. Possible shapes of reward curves that temper issuance, constructed by altering the exponentiation of D in the term added to the denominator of the current reward curve equation. The preferred range from Figure 2 is indicated in grey.

Which reward curve that is optimal will depend on how various trade-offs discussed in Sections 2-3 should be balanced, and this will naturally be subject to diverse opinions. The red reward curve is the only option that remains fully within the preferred range presented in Figure 2, but the orange and purple reward curves are also almost within that range. Speculatively, it might be easiest to reach an agreement on one of these three shapes, scaled as desired.

Note concerning the red reward curve that the exponentiation by 2.5 in the added term naturally combines with the exponentiation by 0.5 of the current reward curve. The resulting equation for issuance yield can therefore be rewritten simply as:

which just requires an adjustment to k. Specifically for the plotted curve, k must be reduced from around 35.4\times10^6 to 1.95\times10^6. We could thus refer to the red shape as a “cubed” reward curve and the orange shape as a “cubed+” reward curve, with the purple then denoted “squared+”, etc. The yellow curve is created by increasing the exponent from 3 to 4 in the previous equation (thus denoted “quartic”). That reward curve brings issuance very close to zero at high quantities of stake.

Staking yield with MEV

The staking yield, inclusive of 300k ETH MEV per year (roughly the long-running average), is shown for the reward curves of Figure 3 in Figure 4. To make the discussion more tangible, equilibria under a hypothetical blue supply curve are marked by a circle, providing plausible scenarios a few years from now. Note that the supply curve will be nearly vertical at short time-scales due to frictions in the decision to stake (even when ignoring the deposit queue), but bends with time, and the focus here is the long run. The hypothetical supply curve would result in an equilibrium of 50M ETH staked and a yield of 2.9% under the current reward curve.

The other reward curves produce equilibria within 34M-40M ETH staked and a yield of 2-2.3%. It can be interesting to consider an extreme low-yield scenario, where the supply curve is much lower than the most likely outcome—perhaps a decade or two from now. Such a hypothetical supply curve is indicated by a dashed blue line. There should hopefully be rather broad agreement that the equilibrium under the current reward curve is not desirable in this scenario. At a staking yield of around 1.9%, issuance is 1.7M ETH—so high that it is located outside the boundaries of Figures 1-3. There is furthermore no longer a trustless sound primary currency in the Ethereum economy in the form of non-staked ETH. All holders of ETH or its derivatives are potentially worse off than under an equilibrium enforced at a lower quantity of stake.

Figure 4. Staking yield, inclusive of 300k ETH/year in MEV, for tempered reward curves of different shapes. Equilibria with a hypothetical supply curve a few years from now (blue) are indicated by circles. An unlikely very low supply curve is also illustrated by the dashed blue line, with hypothetical equilibria indicated by squares.

The equilibrium quantity of stake for the outlined reward curves varies between around 57M-80M ETH with the very low supply curve. That is above a desirable level. However, this is really the extreme scenario, where MEV burn has not materialized, and half of the token holders are ready to assume—directly or through delegation—the costs of staking under a total staking yield of 0.75%. Reducing issuance further to temper staking might not be desirable. The black dashed line indicates the outcome with no issuance at all. The equilibrium quantity of stake is then not reduced substantially relative to the equilibrium with the lower reward curves, in my view rendering such an approach an unmotivated sacrifice of solo staking viability and increase in consensus design complexity (see also Section 2.3 and Section 3).

Issuance yield

Figure 5 instead shows issuance yield with no MEV, which could be the situation after incorporating a fully successful MEV burn mechanism. The equilibrium under the investigated reward curves then ends up at around 30M ETH staked for the outlined hypothetical supply curve. Even under the very low supply curve, the equilibrium is pushed down to between 39M-57M ETH: MEV burn will be a key component for achieving a low quantity of stake if the issuance yield remains positive.

Figure 5. Issuance yield for tempered reward curves of different shapes, which would also be the staking yield under full MEV burn. Equilibria with a hypothetical supply curve (blue) a few years from now are indicated by circles. An unlikely very low supply curve is also illustrated by the dashed blue line, with hypothetical equilibria indicated by squares.

4.2 Issuance floor

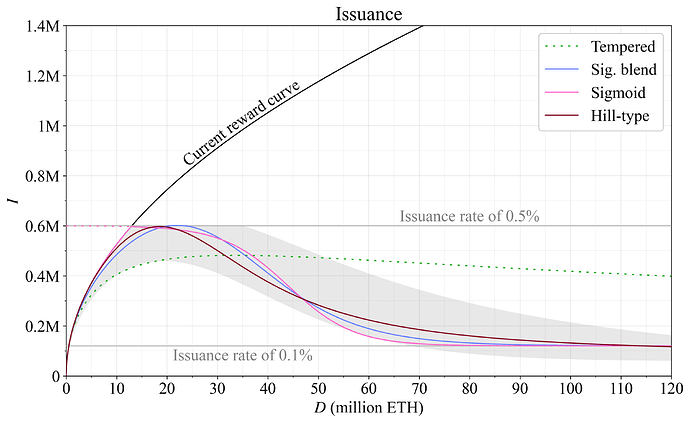

The reward curve can also be designed to smoothly transition from the current reward curve to an issuance floor I_f, set at some desirable level. Three examples are shown in Figure 6. The light blue curve is constructed by blending with a sigmoid weight computed as

The central point of the blend was set to D_c=32\times10^6 and the steepness of the transition set to k=7\times10^6. This can be adjusted as desired. The curve then blends (1-w)I_r+wI_f, where I_r is issuance for the current reward curve [i.e., I_r(D)] and I_f is set to 120\,000 (i=0.1\%). Another solution is to simply blend between the maximum and minimum desired issuance level by replacing I_r by, for example, a fixed 600\,000 ETH. This is done with the pink curve, illustrating a piecewise option of transitioning from the current reward curve at the point where the sigmoidal weight intercepts it.

A third option is to employ a Hill-type equation:

It is a fairly clean construction, relying on a specified halfway point D_{h} between I_r and I_f, as well as the exponent n that further determines the shape. The brown curve was constructed from D_{h}=30\times10^6 and n=3, setting I_f=90\,000.

Figure 6. Three reward curves that asymptotically approach an issuance floor around i=0.1\%. The preferred range outlined in Figure 2 is once again indicated in grey.

Figure 7 shows the staking yield inclusive of 300k ETH of MEV/year, investigating the same features as in Figure 4. The reward curves with an issuance floor provide an equilibrium staking of around 60M ETH for the low supply curve, approximately in line with the orange reward curve of the previous examples. Since issuance is kept fixed around the floor, the proportion of the MEV (“No issuance”) relative to issuance+MEV remains approximately constant at higher quantities of stake. Figure 8 instead shows the outcome with only issuance yield.

Figure 7. Staking yield, inclusive of 300k ETH/year in MEV, for reward curves that asymptotically approach an issuance floor. Equilibria with a hypothetical supply curve a few years from now (blue) are indicated by circles. An unlikely very low supply curve is also illustrated by the dashed blue line, with hypothetical equilibria indicated by squares.

Figure 8. Issuance yield for reward curves that asymptotically approach an issuance floor, which would also be the staking yield under full MEV burn. Equilibria with a hypothetical supply curve a few years from now (blue) are indicated by circles. An unlikely very low supply curve is also illustrated by the dashed blue line, with hypothetical equilibria indicated by squares.

4.3 Piecewise constructions

Smooth reward curves are not strictly about aesthetics. It seems reasonable to ensure that there is no discontinuity that can influence the decision to stake, for example making cartelization attacks more attractive at some specific range or point. The overarching issuance policy expansion path is arguably also smooth. However, linear piecewise constructions bring the benefit of simplicity, and the downsides may not be sufficient to forego that. Figure 9 shows three linear constructions. The dark blue and cyan reward curves reduce issuance by 1 ETH for every 100 ETH that is staked, in between an issuance rate of 0.5% and 0.1%. The beige reward curve is instead symmetrical around the mid point of 60M ETH, reducing issuance by 1 ETH for every 125 ETH that is staked while taking the issuance rate from 0.5% to 0.1%.

These constructions provide some tangible anchors that might simplify communication. Issuance is always easy to calculate, and at an issuance rate of 0.5%, the issuance yield becomes 4% at 15M ETH (1/8 of the supply) staked, 3% at 20M ETH (1/6), and 2% at 30M ETH (1/4). An issuance yield of 1% is reached at 40M ETH or 45M ETH, respectively, for the dark blue and cyan reward curve, and at 60M ETH (1/2), the issuance yield is 0.33% or 0.5% respectively.

The dashed dark red reward curve simply sets issuance to an issuance rate of 0.5%. This type of reward curve has been referred to as “capped issuance” and was implied in a proposal by Vitalik in early 2021. It is not necessarily an endgame policy and would have to be adopted with the understanding that we might return to the conversation again in a few years. It would enable us to address the issue of a growing quantity of stake so that we can focus on other topics for a few years—until kinks related to for example MEV and Orbit SSF have been worked out. As previously mentioned, I find this type of solution appealing, but from the community’s point of view, there seems to be an apparent appetite for definite answers.

Figure 9. Illustrating piecewise constructions with issuance changing linearly or remaining fixed.

5. Conclusions and important questions

There are several downsides to an issuance policy that provides 100% certainty of tempering the quantity of stake to reasonable levels, as opposed to one that provides 99.9% certainty. This post has suggested practical endgame reward curves that will temper the growth in the quantity of stake without introducing unnecessary political, analytical, and implementational complexity. My personal preference, fitting within the outlined preferred range, would be to use the shape of either the orange, red, or purple tempered reward curves presented in Section 4.1, where the red curve fits fully within the preferred range. These curves make an equilibrium at a high quantity of stake very unlikely, yet can allow small solo stakers to always receive positive regular rewards when performing their duties adequately. Simply setting issuance to a 0.5% issuance rate for now, as illustrated by the red dashed curve in Figure 9, would in my view also be an appealing solution. The idea would be to then return to the conversation in a few years if necessary, once various issues such as MEV burn have been worked out. But this solution may not appeal to the Ethereum community.

A clear benefit of a practical endgame is that it has less dependencies and will not fail if MEV burn does not come to fruition under a low supply curve. This allows us to address issuance without unnecessary delay. On a related note, focusing on unrealistic scenarios—such as everyone staking at near-zero issuance yields—would be unfortunate, because we might then fail to move forward when a change would be very beneficial.

Questions for the community and researchers

Community feedback and debate would be welcome. For example:

- Is it ever okay to have solo stakers that do not pool block proposal rewards lose ETH while attesting diligently, as long as they attain a positive expected yield in the long run from infrequent block proposals? Should it be strictly avoided, or would it be acceptable at some higher deposit size to stem further growth, say at 60/90/120M ETH staked? At what percentage of being offline over a year would it be acceptble with negative yield?

- What should the issuance (or equivalently, issuance yield) be set to at 15M, 30M, 45M, 60M, 75M, 90M, and 120M ETH staked? Community members and researchers are welcome to specify their own “preferred range”.

- Given current uncertainty related to MEV and the benefits of reducing issuance, would you be supportive of simply fixing issuance at an issuance rate of 0.5% (grey line in the figures; red dashed line in Figure 9) for the next 3/4/5/6 years, with a commitment to return to the issue after that?

From a research perspective, given the dependency on MEV burn and Orbit SSF, it seems that a lot would be gained by mapping out the likelihood of implementing these mechanisms within specific time frames. This is something that we as consensus researchers could do while we diligently keep working on the implementation details.